(Updated May 13, 2024)

I have written about Settela before. She was also known as Anna Maria Steinbach. One of the reasons I want to highlight the sad story of Settela is because there is a chance she may be related to me, be it via marriage or one of my cousins. Yet, there is another clear indication of how near the Holocaust still is. She was a Dutch girl murdered by the Nazis in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Initially identified as a Dutch Jew, but in 1994 it emerged she was actually Sinti. Now through this post, I will be using the name gypsies, because that is what the group of Romani and Sinti were called during World War II, and indeed that is how they still often refer to themselves.

Settela was born in 1934 in Born—other sources say Buchten or Geleen, but that area in part of Limburg in the Netherlands is quite small and within a cycle distance of each other. In her youth, she travelled through the Limburg countryside with her nine brothers and sisters.

Susteren was one of the permanent locations of the Steinbach family—on the Baakhoverweg, on the slope of the road, next to the orchard of de Zeute, where the family caravans resided. Local residents remember that the children of the Steinbachs regularly came to ask for water. On summer evenings, they could hear the melodious sounds of the family’s violins in the village.

In 1943, the Steinbach family moved to the well-known caravan camp ‘De Zwaaikom’ in Eindhoven. The camp, built in 1929, was designated by the government after the travel ban in the summer of 1943 as one of the central camps for gypsies.

Early Tuesday morning, 16 May 1944, Settela and her family were awakened by banging on the trailer and screams. It was a raid. The police officers and land rangers had a list of the gypsies staying at the caravan camp and carried out the raid. Eventually, 21 (especially women and children) were driven out of the camp (via the police station) to Eindhoven station. Some men were arrested a week earlier and taken to Camp Amersfoort. So was the fate of Settela’s father.

At Centraal Station, Settela had to board a passenger train with the other arrested Sinti and Roma, which travelled to Den Bosch, where an additional 51 people boarded. It then continued the journey north to Camp Westerbork around 4 o’clock. A few days later, they deported her to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

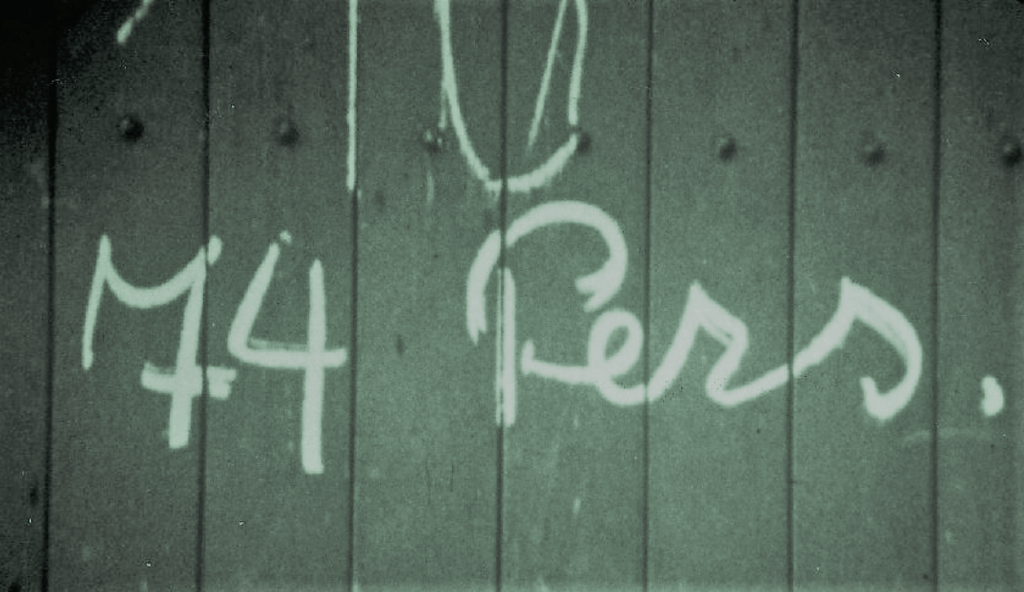

Right before the doors were about to close, she stared through the opening at a passing dog or the German soldiers. Rudolf Breslauer, a Jewish prisoner in Westerbork, who was shooting a movie on orders of the German camp commander, filmed the image of Settela’s fearful glance staring out of the wagon. Crasa Wagner was in the same wagon and heard Settela’s mother call her name and warn her to pull her head out of the opening. There was something peculiar about the car she was in. She noticed it had vertical planks, in contrast to most of the other rail cars of the 19 May transport. Most cars had planks arranged horizontally. Why that is, or its importance, I do not know.

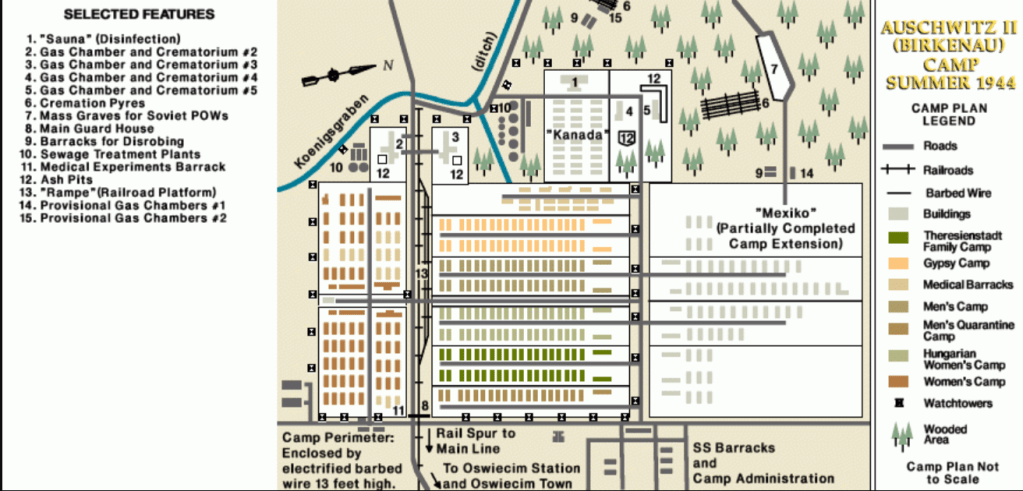

On 22 May, the Dutch Romani, among them Steinbach, arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. They were registered and taken to the Romani section. Romani, fit to work, were dispatched to the ammunition factories in Germany. The remaining 3,000 Romani met their fate at the gas chambers to their deaths in mid-summer 1944. Steinbach, her mother, two brothers, two sisters, aunt, two nephews and niece were part of this latter group. Of the Steinbach family, only the father, Heinrich ‘Moeselman’ survived. He died in 1946 and was buried in the cemetery of Maastricht.

After the war, the image of Settela became famous. She was known as “The Girl with the Headscarf” and was assumed to be Jewish. Her name and Sinti identity were established in 1994 by Dutch journalist Aad Wagenaar. Settela became a symbol of the Roma and Sinti genocide during the Holocaust. At age 9, the Nazis murdered her at the Camp in August 1944. Based on the evidence available to date, historians estimate that the Germans and their allies killed between 250,000 and 500,000 European Roma during World War II.

Seventy-nine years ago, Settela was 9 when she died in 1944. She would have been 88 today if she lived. Who knows what her future would have held if she had been allowed to live? She was born so near where I grew up—I could have easily bumped into her.

A poem about the Porajmos

In shadows deep, they wandered free,

Their laughter danced with melody,

Beneath the moon, they sang their song,

Yet soon would come a night so long.

Across the land, a darkness spread,

Where hatred reigned and reason fled,

Their wagons halted, spirits worn,

As evil whispered, death was sworn.

In camps of sorrow, they were led,

Where chains of cruelty left them bled,

Their culture, language, torn apart,

By hearts of stone and poisoned dart.

Yet in the midst of darkest night,

A flame of hope, however slight,

For even as the fires burned,

Their spirit strong, they never turned.

With courage forged in trials dire,

They kindled flames of fierce desire,

To rise again, from ashes grey,

And tell the world of yesterday.

For though the scars may still remain,

Their voices echo, not in vain,

In memory’s embrace, they stand,

A testament to love’s command.

So let us nevermore forget,

The lives that time would soon regret,

In reverence, we honor those,

Whose stories whisper, never close.

Sources

https://www.yadvashem.org/blog/remembering-settela.html

https://westerborkportretten.nl/sinti-en-romaportretten/settela-steinbach

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/genocide-of-european-roma-gypsies-1939-1945

Leave a comment