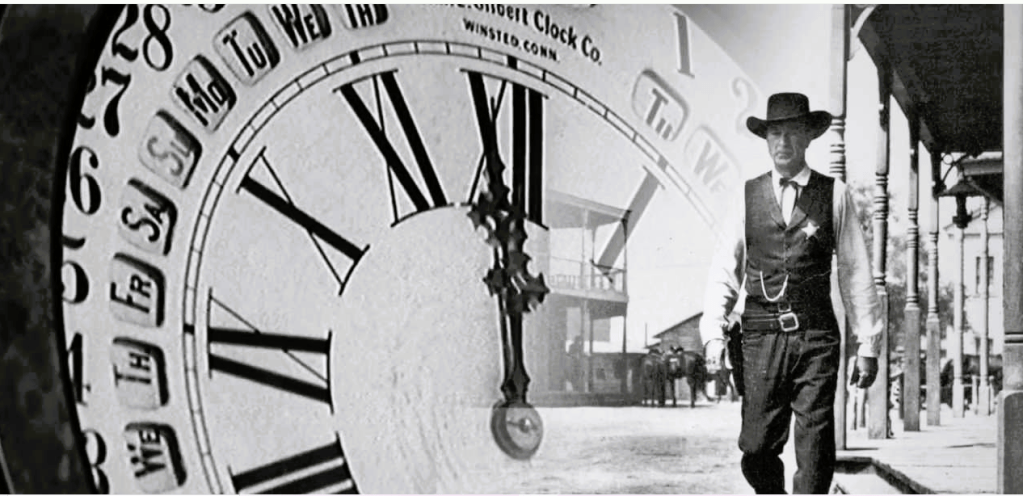

High Noon is my favourite Western and one of my favourite movies overall.

The Western genre has long held a special place in American cinema, representing ideals of heroism, rugged individualism, and the triumph of good over evil. However, not all Westerns adhere to a singular vision of these ideals, and one film that provoked significant controversy was High Noon (1952), written by Carl Foreman and directed by Fred Zinnemann. Two of the most prominent figures in Western filmmaking, John Wayne and Howard Hawks, vocally opposed the film, citing its portrayal of heroism, its perceived political message, and its departure from traditional Western values. Their critique of High Noon illuminates a larger conversation about American ideals during the Cold War and the role of cinema in reflecting or shaping those values.

John Wayne’s Critique: An Attack on American Values

John Wayne, often regarded as the quintessential Western hero, found High Noon deeply offensive on both artistic and political grounds. Known for playing characters who embodied courage, loyalty, and stoic self-reliance, Wayne viewed the film’s narrative as a rejection of these values. At the heart of his critique was the portrayal of Marshal Will Kane, played by Gary Cooper, as a man who, despite his heroism, is abandoned by the townspeople he seeks to protect. Kane’s isolation as he pleads for help against a gang of outlaws runs counter to the traditional Western narrative, where communities rally around their defenders, and heroes do not beg for assistance.

Wayne saw this as more than just poor storytelling; he believed it was a subversive commentary on American society. Wayne’s reaction to High Noon was particularly coloured by the film’s political undercurrents. Written by Carl Foreman, who would later be blacklisted for alleged communist ties, the film was seen by Wayne as an allegory for the era’s political climate, particularly the issue of McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist. In High Noon, the townspeople’s refusal to stand by their lawman is often interpreted as a critique of those who failed to stand up against political persecution during the Red Scare. Wayne, a staunch supporter of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), viewed the film as an unpatriotic and un-American attack on those like himself who were leading the fight against communism.

For Wayne, who was deeply involved in Hollywood’s conservative movement, High Noon presented a narrative where American values were being undermined. Instead of standing united against a common threat, the film portrayed a community willing to abandon its responsibilities. Wayne famously remarked that High Noon was “the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life,” believing that it depicted Americans as cowardly and unwilling to face down evil—a sentiment entirely at odds with the principles Wayne cherished, especially in the context of the Cold War.

Howard Hawks: A Defense of the Traditional Western Hero

Howard Hawks, one of the most influential directors of Westerns, shared Wayne’s disdain for High Noon. However, his objection was primarily rooted in the film’s depiction of heroism. Hawks had directed John Wayne in many movies and was known for his portrayal of strong, self-reliant men who faced adversity with unwavering courage. To Hawks, the notion of a Western hero, like Will Kane, going from person to person, asking for help, was not just unrealistic but also antithetical to the essence of the genre.

Hawks believed that the Western hero should embody independence and strength, characteristics that were missing from Kane’s portrayal in High Noon. In Hawks’ view, a true Western hero would never beg for assistance, especially not from a community that would abandon him. Instead, the hero should confront danger with a small, trusted group of allies or, if necessary, alone. Hawks thought that the film failed to capture the spirit of camaraderie and loyalty that defined the best Westerns. His distaste for High Noon was so strong that he felt compelled to make his own counter-argument in cinematic form.

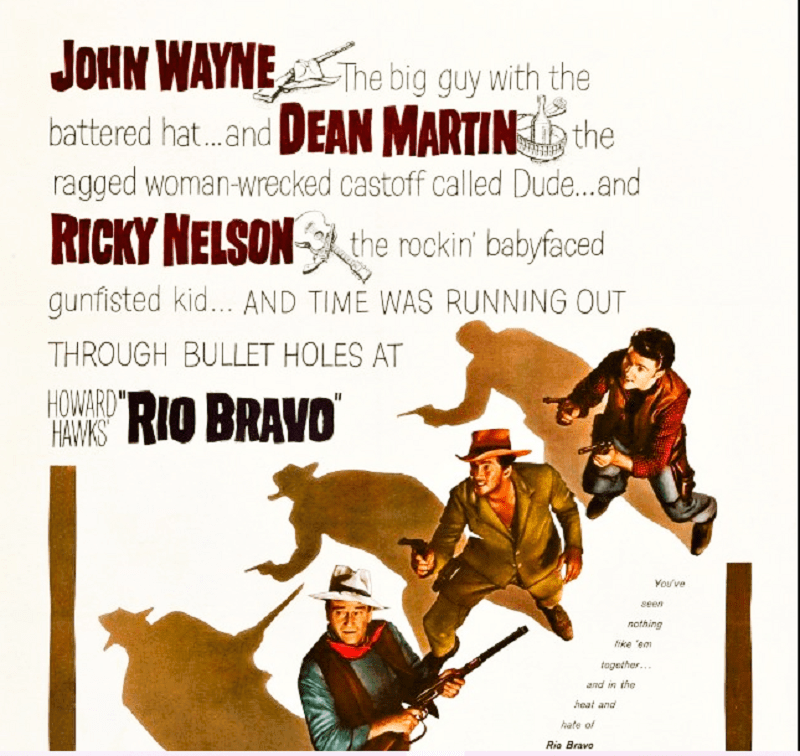

In 1959, Hawks directed Rio Bravo, a film that many critics regard as a direct response to High Noon. In Rio Bravo, John Wayne plays Sheriff John T. Chance, a man who faces overwhelming odds but refuses help from anyone who isn’t trustworthy or willing to stand beside him. Unlike High Noon, where the townspeople’s cowardice defines the plot, Rio Bravo emphasizes loyalty and the power of a few brave individuals to stand against evil. In Hawks’ vision, a hero does not need the approval or support of a cowardly community to stand up for what is right; instead, he does so because of an inherent sense of duty and integrity.

Cultural and Political Context: High Noon as Political Allegory

Beyond the personal and artistic preferences of Wayne and Hawks, their objections to High Noon were heavily influenced by the political climate of the time. The early 1950s, when the film was released, was marked by the Red Scare and the rise of McCarthyism, where fear of communism led to widespread paranoia and political persecution. Carl Foreman, the screenwriter of High Noon, had been called to testify before HUAC, and his refusal to fully cooperate resulted in his blacklisting. As a result, many saw High Noon as a veiled critique of McCarthyism, with the cowardly townspeople representing those who failed to stand up against injustice during the Hollywood blacklist and beyond.

For Wayne and Hawks, both strong anti-communists and supporters of the blacklist, this allegory was deeply offensive. They saw the film not as a brave commentary on political persecution but as a subversive attack on American values. In their view, High Noon suggested that Americans, when faced with danger, would retreat into fear and cowardice, leaving the individual to face the threat alone. This was a sharp contrast to their own belief in American exceptionalism and the idea that the country, especially in its Western mythos, was defined by the collective strength of individuals standing up for what was right.

John Wayne and Howard Hawks’s objections to High Noon were not simply critiques of its artistic choices or narrative style. Instead, their responses were deeply intertwined with their views on American values, particularly in the context of the Cold War and the political tensions of the 1950s. For Wayne, the film’s portrayal of a community that abandons its hero was an attack on the idea of collective responsibility and patriotism, while for Hawks, the film undermined the strength and self-reliance of the traditional Western hero. Both men saw the film as an affront to the ideals they held dear, and their opposition to it culminated in the creation of Rio Bravo, a film that reinforced their vision of American heroism: intense, loyal, and resolute in the face of adversity.

In the end, the debate between High Noon and Rio Bravo represents more than just a difference in cinematic taste—it is a reflection of broader cultural and political divisions in mid-century America. The Western genre, often seen as a simple celebration of frontier life, became a battleground for competing visions of what it meant to be an American and how the country should face its moral and political challenges.

Sources

https://www.pastemagazine.com/movies/john-wayne/high-noon-rio-bravo-western-ideology

https://screenrant.com/john-wayne-high-noon-movie-turned-down-reason/

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment