Ninety-eight years ago today, the classic science fiction movie Metropolis was released. Watching it again recently, I was struck by how fresh and visually striking the film still feels, even after nearly a century.

However, Metropolis is more than just a sci-fi masterpiece; it also serves as a fascinating snapshot of the political and social landscape of its time—not only through its themes but also in the lives of those who brought it to life.

The central drama of the movie lies in the stark divide between two social classes: the laborers, numbed by monotonous and grueling tasks, and the affluent class of owners, managers, and their clerks, portrayed as diligently engaging in mathematical and scientific calculations to sustain a vast industrial enterprise. This upper class enjoys a life of luxury and indulgence. Early in the film, during a lavish party in a setting described as “the eternal garden,” a striking interruption occurs. A woman appears in the doorway, surrounded by impoverished children, and extends her arms protectively over them. She addresses the partygoers, declaring, “These are your brothers, your sisters.” The revelers are stunned into silence, captivated by her presence. Among them is the son of the city’s industrial magnate and ruler, who gazes at her, deeply moved. The woman, named Maria, is symbolically portrayed as a virgin.

In 1927, Germany stood on the brink of profound social and political upheaval. The Nazi Party, though still relatively small, was gaining traction and beginning to exert an influence that would shape the nation’s trajectory in the years to come.

UFA GmbH, the studio responsible for distributing Metropolis, faced significant financial difficulties and was acquired in 1927 by Alfred Hugenberg, a prominent politician and media tycoon. Hugenberg was the chairman of the German National People’s Party, a conservative nationalist party. As its leader, he played a crucial role in Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, ultimately supporting Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor in 1933 and serving in his first cabinet.

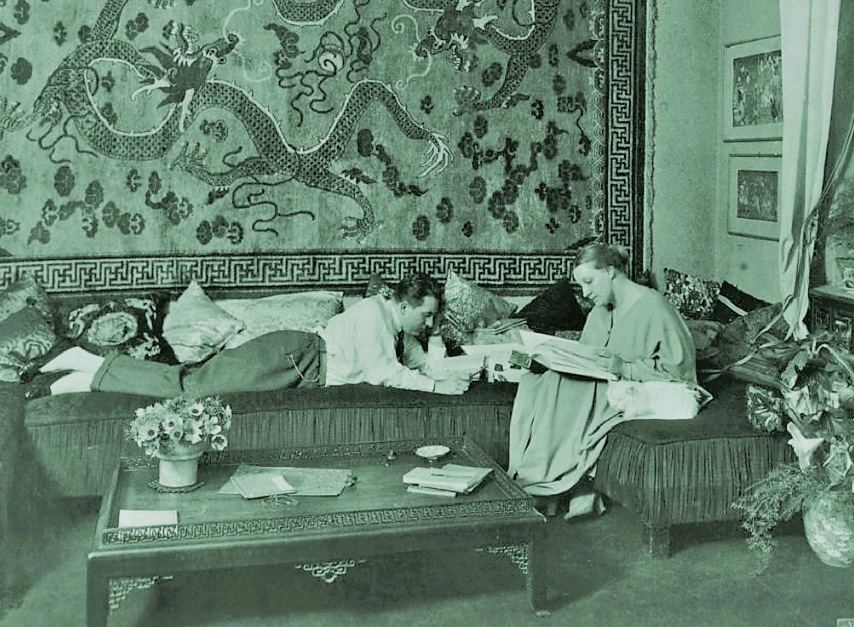

Fritz Lang, the director of Metropolis, and his wife, Thea von Harbou, who authored both the novel and the screenplay, initially showed an interest in the Nazi Party, reflecting the complex and fraught political landscape of the time.

Metropolis presents a chilling vision of a future defined by extreme social inequality, visually represented through its vertical structure: the intellectual elite revel in luxury within towering skyscrapers. At the same time, the industrial working class toils relentlessly beneath the earth’s surface. The film critiques modernity and technological progress but ultimately finds a glimmer of hope in the aftermath of Metropolis’s apocalyptic collapse. Similarly, the New Objectivity style that later emerged in the Weimar Republic served as a counterpoint to the anti-realist Expressionism embodied by the film. While Metropolis weaves a complex narrative addressing ambition, greed, and the transformative effects of technology on individuals and society, this essay hones in on one central theme: hierarchy. By analyzing the film’s set design, visual storytelling, and the ‘architecture’ of its plot, we can explore its portrayal of hierarchy among humanity, machinery, and the city itself.

Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou collaborated on several iconic films during their partnership. In addition to Metropolis, they created the 1931 classic thriller M, starring a young Austro-Hungarian Jewish actor, László Löwenstein—better known as Peter Lorre.

When Adolf Hitler rose to power, Peter Lorre fled Germany due to the anti-Semitic laws imposed by the regime. Another star of Metropolis, Brigitte Helm—who played both Maria and the Tin Machine—also fell afoul of the Nazis. She faced persecution for “race defilement” after marrying her second husband, Dr. Hugo Kunheim, an industrialist of Jewish heritage. The couple emigrated to Switzerland in 1935, never to return to Germany.

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, admired Fritz Lang’s work. Despite banning Lang’s 1933 film The Testament of Dr. Mabuse—claiming it depicted that “an extremely dedicated group of people are perfectly capable of overthrowing any state with violence”—Goebbels still offered Lang the position of head of UFA, Germany’s leading film studio.

Lang, however, declined the offer and left Berlin on July 31, 1933. Increasingly alarmed by the Nazi Party’s power and the introduction of the Nuremberg Laws, Lang decided to emigrate. Although his mother had converted to Catholicism and he was raised Catholic, the Nuremberg Laws classified both him and his mother as Jewish. While Lang had initially shown some sympathy toward the Nazi Party, he quickly became disillusioned. Meanwhile, Thea von Harbou remained a committed Nazi supporter. The couple divorced on April 26, 1933.

Lang emigrated to the United States, where he enjoyed a successful career in Hollywood, directing films such as The Return of Frank James (1940), starring Henry Fonda. In contrast, Thea von Harbou stayed in Germany and continued working in the film industry, producing works with an unmistakable National Socialist worldview.

Today, many people might only recognize Metropolis from Queen’s Radio Ga Ga music video, unaware of the film’s rich historical and cultural significance. The movie remains a remarkable artifact, reflecting not just a vision of the future but also the tumultuous social and political landscape of its time.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolis_(1927_film)

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0017136/?ref_=ttmi_ov_i

https://www.bfi.org.uk/film/bda6ff8a-ed7e-5942-980d-c2910c0120ec/metropolis

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Metropolis-film-1927

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment