It is a sensitive and often overlooked subject. I’m not certain whether suicides were completely included in the Holocaust statistics. In this blog, I focus specifically on the situation in the Netherlands, but I believe this was likely the case in all occupied territories—and possibly beyond.

Suicide emerged as a tragic yet significant response to the relentless persecution and trauma faced by individuals both before and during the war, as well as in its immediate aftermath. The act of taking one’s life became a means of escaping impending doom, a desperate assertion of control in an otherwise powerless situation, and, in some cases, an ultimate act of defiance. This essay explores Holocaust-related suicides in three critical periods: before the war, during the Holocaust, and in its aftermath.

There is strikingly little written about this subject, and a list of names or a memorial book does not seem to exist.

One example:

At the beginning of 1940, Jacob Keesing (Amsterdam, April 21, 1889) lived with his wife, Esperance Keesing-Peekel (Amsterdam, April 20, 1893), at Ceintuurbaan 247 in Amsterdam. They lived together with Suzanne Keesing (Amsterdam, February 26, 1877) and Marianne Keesing (Amsterdam, October 24, 1882), two half-sisters of Jacob. The four formed a close-knit family. Jacob Keesing worked for the family business, “Uitgeverij Keesing,” which was led by his brother Isaac (Amsterdam, August 1, 1886). Jacob was in charge of the Belgian branch of the publishing house.

Already in the 1930s, the four feared the virulent antisemitism of Nazi Germany. When German troops invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, they immediately rushed to IJmuiden in an attempt to escape to England by ship. However, they were unable to arrange passage. Hoping to find a skipper who would take them, they rented a room on Velserduinweg. When it became clear that the German occupation was a fact, the four saw no other way out than to take their own lives.

New data on the extent of Jewish suicides was published in 2001. According to newly recovered statistics from the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics for the period 1940–1943, the numbers are approximately 257 (1940), 36 (1941), 248 (1942), and 169 (1943). The highest percentage occurred in May 1940. In his extensive standard work, Lou de Jong states that at least 120 suicides were reported in Amsterdam that month and about thirty in The Hague. He makes no statement about the rest of the country. De Jong notes that the figures only account for “successful” suicides; according to him, there were likely just as many ‘failed’ attempts. For example, Elize Jeanette de Jong-Groenberg (Nijmegen, June 23, 1918) jumped from her backyard balcony in May 1940. She survived the fall, but that was only a temporary reprieve—she later perished in Sobibor.

Notably, a large number of prominent individuals saw no way out after the German invasion. In Amsterdam, alderman and demographer Emanuel Boekman (Amsterdam, August 15, 1889) and banker Siegfried Paul Daniel May (Amsterdam, September 20, 1868), among others, took their own lives along with their spouses. The latter was a co-partner in the bank Lippmann, Rosenthal & Co on Nieuwe Spiegelstraat in Amsterdam (not to be confused with the German looting bank on Sarphatistraat, which used the same name). In some cases, the ultimate self-sacrifice of a public figure was recognized by onlookers as a warning. In The Hague, city council member Michel Joëls (The Hague, November 24, 1881) took his own life, after which Mayor S.J.R. de Monchy delivered an emotional eulogy before The Hague city council. The mayor used the occasion to warn of the impending terror of Nazism.

The phenomenon of suicide was not limited to the first days of the occupation.

From July 1942 to May 1943, the Jewish Council of Amsterdam kept a list of suicides. However, not all cases were recorded. Thanks to stories from relatives, more data is becoming available today. A former neighbor, for example, recalled that Leentje Weenen-Löwenstein (Amsterdam, March 6, 1865) drowned herself in the Ringvaart near the Transvaalkade out of fear for what was to come. He wrote: “She rarely went outside anymore. It is incomprehensible how she managed to leave the house at night and find the water quietly.” Likewise, Klara Stern-Gomperts (Mönchengladbach, May 4, 1907) took her own life in August 1942 after receiving a deportation order.

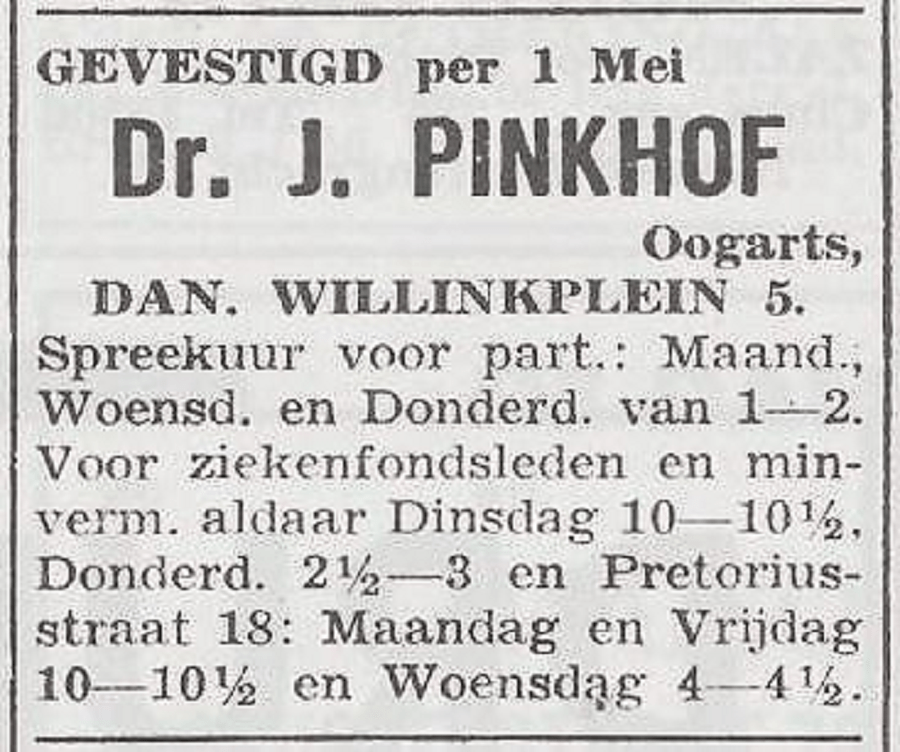

More well-known is the story of ophthalmologist Dr. Jacob Pinkhof (Amsterdam, February 15, 1895). In September 1942, he ended his life along with his wife and three children through gas poisoning (asphyxiation by gas).

It is often difficult to determine who committed suicide, especially when deaths were not officially reported. It happened, for example, when a person’s whereabouts had to remain secret. The couple Jacob Samuel Wijler (Lochem, March 1, 1884) and Elisabeth Rose Wijler-Kolthoff (Almelo, July 8, 1887) were in hiding near Epe. Their daughters, Martha Rose (Zierikzee, October 13, 1919) and Rose Helene (Apeldoorn, March 13, 1922), were hiding elsewhere. In January 1943, the daughters were betrayed and arrested. A few months later, their parents, overwhelmed with grief and despair, took their own lives. Their deaths were only made known after the war.

Apart from some statistical data, little is still known about Jewish suicides during World War II. The topic remains sensitive. The Digital Monument provides an opportunity to recognize these war victims (for that is what they are). In the coming years, more information and stories are expected to emerge, helping to rescue this group from oblivion.

The photo at the top of the blog features Marianne Lisser and her husband, Robert Paul Belinfante. Marianne was the second child of Hartog Lisser and Abigael Benjamins.

On May 13, 1940, in Laag-Keppel, Marianne and Robert attempted suicide. At the time, Marianne was pregnant. Robert did not survive, while Marianne did, but she tragically lost the baby. She later passed away while in hiding on January 10, 1944

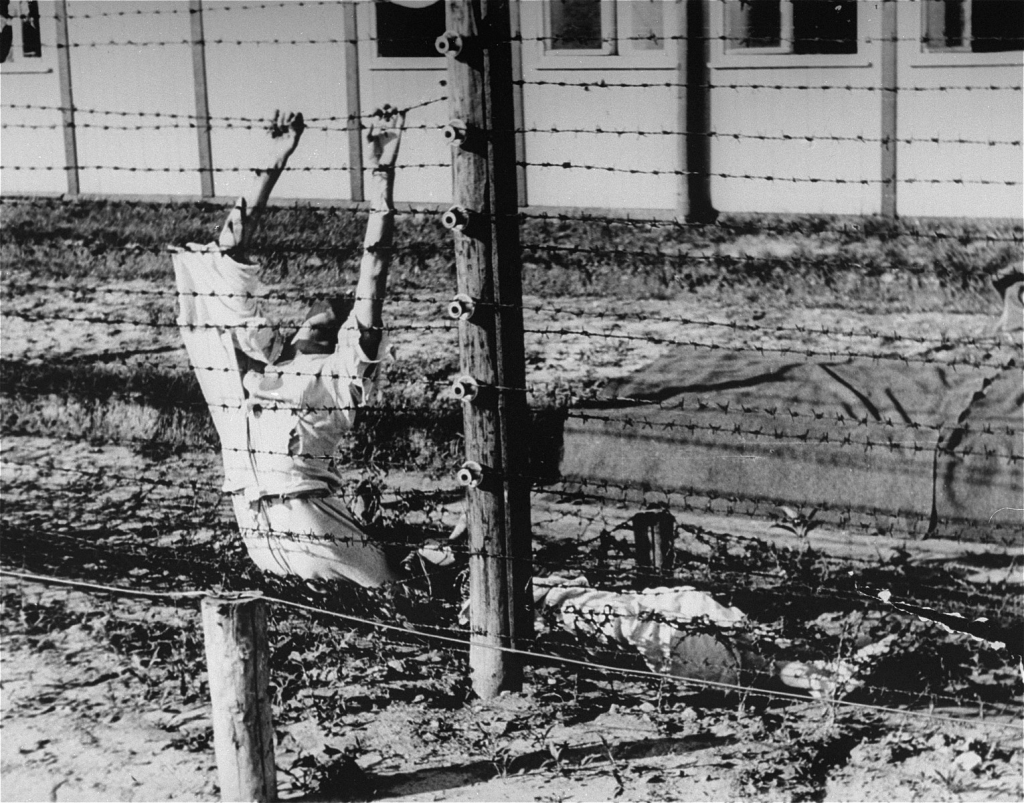

In concentration camps, some prisoners deliberately threw themselves onto electrified fences to end their suffering.

The accounts provided by former prisoners suggest that the motives for suicide in concentration camps can be categorized into two main groups: “direct” and “indirect” motives. The first group includes factors directly related to the traumatic experiences of imprisonment, such as the conditions of incarceration, shifts in the camp hierarchy, extreme deprivation, starvation, diseases, grueling labor, and the constant threat of punishment or death. These factors were central to the prisoners’ daily suffering and contributed to feelings of hopelessness.

The second group encompasses psychological and somatic traumas, along with personal circumstances that may have triggered suicidal behavior. This category also includes intra-psychological factors, such as mental illness, that contributed to the decision to attempt suicide.

Among the most common motives for suicide observed in the concentration camps were psychological disturbances—primarily depression of varying severity and origin—somatic illnesses, fear of torture, anxiety over being denounced, the loss of a loved one, romantic disappointments, physical assault, and strong feelings of patriotism and altruism. These factors often compounded the unbearable strain of camp life, leading many to take their own lives.

Some Individual Stories

Sara Blom-de Vries

On Tuesday, May 14, 1940, at 11:50 PM, the daily report of the police in The Hague states:

“The watch commander of Prinsestraat reports that Mrs. S. Blom-de Vries, 62 years old, residing at Plaats 9 A, attempted suicide in her home by means of gas asphyxiation. She was taken by the municipal health service (G.G.D.) to the Ramaer Clinic.

Her family resides at Nieuwe Parklaan 130 and Gevers Deynootweg. The woman’s name is Sara de Vries. She was born in Amsterdam on September 18, 1876, and is the widow of J. Godschalk-Blom. She was discharged from the Ramaer Clinic the following day and now resides at Plaats 9 with her son.”

Jacob van Gelderen

Jacob van Gelderen (Bob’s nickname), economic specialist of the SDAP (Social Democrat Labor Party), was born in Amsterdam on March 10, 1891, and died in The Hague on May 14, 1940.

Van Gelderen, who, after completing the Public Trade School in 1910, obtained secondary certificates in Economics and Statistics, worked between 1911 and 1919 at the Bureau of Statistics of the Municipality of Amsterdam. In his youth, he was active in Poale Zion. Initially, he was part of the left wing of the SDAP. He was a contributor to Het Weekblad under the editorship of F.M. Wibaut and H. Roland Holst and published economic commentaries under a pseudonym in Het Volk. With his 1913 essay “Springvloed” (Tidal Wave), published in De Nieuwe Tijd, Van Gelderen became one of the pioneers in the field of “long wave” economics. In addition to the typical ten-year fluctuations in the general price level, he observed in several countries an even larger cyclical movement that spanned several decades. His pamphlet Klassenstrijd of volkerenstrijd? Beschouwingen over sociaal-democratie en landsverdediging (Class Struggle or Struggle of Peoples? Reflections on Social Democracy and National Defense, Amsterdam 1915), published under a pseudonym, showed that he was already part of the opposition within the SDAP at that time. In 1916 and 1919, he published several medical-statistical studies with B.H. Sajet, and in 1918 his first demographic article on the influence of war on Amsterdam’s population movements.

At the end of 1919, Van Gelderen left for the Dutch East Indies to build a new statistical service for the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Trade. He became the first director of the Central Bureau of Statistics in Batavia in 1925 (until 1932). In 1923, he confronted former minister M.W.F. Treub, who was then chairman of the Indonesian Enterprise Council, in the pamphlet De theoretische grondslag der progressieve winstbelasting (Theoretical Basis of Progressive Profit Tax, Batavia 1923). He argued that a progressive rate in corporate tax—similar to income tax based on the ability to pay—was theoretically defensible and better suited to the actual situation in the Dutch East Indies than the proportional rate advocated by Treub. His lectures, on agricultural issues, given during a leave in the Netherlands in 1926, were published under the title Voorlezingen over tropisch-koloniale staathuishoudkunde (Lectures on Tropical Colonial Economics, Haarlem 1927). In 1928, Van Gelderen was appointed extraordinary professor of economics at the Law School in Batavia. In his inaugural lecture Het object der theoretische Staathuishoudkunde (The Object of Theoretical Economics, Weltevreden 1928), he provided a brief overview of the history of economic thought, ending with the mathematical school and the Austrian school. The former Marxist Van Gelderen now also criticized the work of K. Marx: “A satisfactory, coherent system of economic analysis cannot be built upon the labor theory of value.” Moreover, according to him, Marx underestimated the importance of agriculture. His rejection of Marxism as an economic-theoretical framework is also evident in his article series Verdieping van het marxisme? (Deepening of Marxism?) published in De Socialistische Gids in 1930. It was a critical review of the book Het economisch getij by long-wave theorist S. de Wolff, which was published in 1929.

During his time in the Dutch East Indies, Van Gelderen was active in the Indonesian Social Democratic Party, of which he became chairman in 1928. He returned to the Netherlands in 1933 and became head of the crisis department at the Ministry of Colonies, which also included economic relations with the Indies. To combat the economic crisis, Van Gelderen advocated for a Dutch Plan-De Man. He became a member of the advisory board of the SDAP’s Scientific Bureau, founded in 1934 to design such a plan. He wrote the chapter on Indonesia for the 1935 Plan van de Arbeid (Labor Plan). In 1937, the Socialist Association for the Study of Social Issues nominated Van Gelderen to succeed R. Kuyper as professor of sociology at the Law Faculty of Utrecht University. In his inaugural lecture, Automatisme en planmatigheid in de wereldhuishouding (Automation and Planning in the World Economy, Amsterdam 1937), he argued for government intervention and international economic and political cooperation. In the same year, he was elected to the Dutch House of Representatives for the SDAP, where he succeeded W. Drees as vice-chairman of the faction in 1939. On May 10, 1940, Van Gelderen—who had recognized the impending crisis in his book De totalitaire staten contra de wereldhuishouding (The Totalitarian States Against the World Economy, Rotterdam 1939)—was among the few members of parliament who managed to reach the House of Representatives. To J.E. Stokvis, he declared: “It’s over.” Like their friends, the Boekman couple, he ended his life four days later, together with his wife, daughter (1919), and youngest son (1922). The eldest son (1917–2000) was serving in the medical corps in Amsterdam at the time of this suicide. He survived the war by going into hiding. After the family grave in The Hague was cleared, the Van Gelderen family was reburied at the National Field of Honor in Loenen in 2021.

Sources

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/nl/page/748060/zelfmoord-poging-14-mei-1940

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/nl/page/343553/onder-druk-van-de-omstandigheden

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/nl/page/749851/zelfdoding-in-de-tweede-wereldoorlog-namenlijst

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/nl/page/358309/marianne-lisser

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13811118.2022.2114866#abstract

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-04463-000

https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/170046,suicide-in-the-nazi-concentration-camps

https://socialhistory.org/bwsa/biografie/gelderen

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to tzipporahbatami Cancel reply