On March 26 and 28, two transports of Slovakian Jews were registered as prisoners in the women’s camp, where they were subjected to forced labor. These were the first transports organized by Adolf Eichmann’s department IV B4 (the Jewish office) within the Reich Security Head Office (RSHA). On March 30, the first RSHA transport from France arrived.

The practice of “selection”—where new arrivals were either chosen for labor or sent to the gas chambers—began in April 1942 and became routine from July onward. Historian Piper notes that this shift reflected Germany’s growing demand for forced labor. Those deemed unfit for work by the SS were s

Men were issued a cap, trousers, and jacket, while women received a dress or skirt with a jacket and a headscarf. Some uniforms, particularly those worn by higher-ranking prisoners like Kapos, had pockets—an invaluable feature for concealing extra rations or small items such as spoons or cutlery. Other prisoners secretly sewed pockets into their uniforms to store essential items.

Eighty years ago, at its peak in January 1945, Auschwitz had a total of 4,480 SS men and 71 SS women working at the camp when Russian soldiers advanced on Auschwitz. On January 27, 1945, the Russians opened the gates and revealed around 6,000 remaining prisoners. Just days earlier, the Nazis had forced nearly 30,000 others to leave on foot amid a blizzard.

Edith’s story as told to author Heather Dune Macadam

“We opened and closed Auschwitz,” says Edith Grosman, reflecting on her harrowing journey. It began in 1942 when she and more than 900 other young Slovak women, many still teenagers, boarded the first official Jewish transport to Auschwitz. For some, it ended on that forced march. Edith, however, was fortunate to survive until the armistice on May 8, 1945.

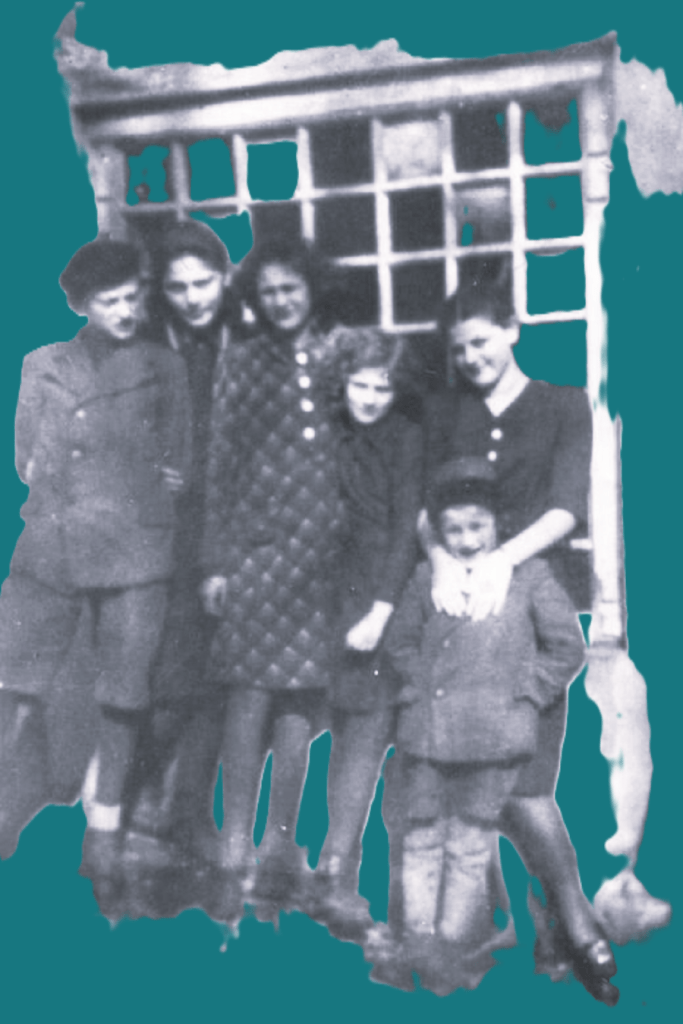

A Family of Children in 1936

Edith and I sit in a Soviet-era hotel room in Poprad, Slovakia, with the snow-covered peaks of the High Tatras visible in the distance. Now 95, she recounts the fateful events that shaped her life. Inspired by her story, I sought to preserve the memories of these remarkable women—by interviewing three survivors and drawing on testimonies from the USC Shoah Foundation digital visual archive. My book, 999: The Extraordinary Young Women of the First Official Jewish Transport to Auschwitz, marks the 75th anniversary of their liberation.

The Deception

“One morning, we woke up,” Edith says, splaying out her arthritic hands, “and saw announcements glued to the sides of houses: all unmarried Jewish girls, aged 16 and older, must report to the school on March 20, 1942, for work.”

At just 17, Edith dreamed of becoming a doctor, while her 19-year-old sister, Lea, aspired to be a lawyer. Those dreams had already been crushed two years earlier when Hitler’s Germany annexed Slovakia. The puppet Slovak government swiftly enacted draconian anti-Jewish laws, including banning Jewish children from education past the age of 14. “We couldn’t even have a cat,” Edith recalls with disbelief.

Her mother, Hanna, protested: “It’s a bad law!” But local officials assured parents that their daughters would be working as “contract volunteers” in a boot factory. Trusting these promises, Hanna packed her daughters’ meager belongings, expecting them home for lunch.

The First Transport

Edith recognized most of the 200 young women lining up—Humenné was a close-knit town. Officials took down their names, a doctor conducted a perfunctory health exam, and then, suddenly, the girls were herded out a back exit towards the train station.

Parents chased after them, desperate for answers. No one provided any.

At the station, the SS loaded the girls onto passenger cars without the chance to say goodbye. Edith heard her mother calling her name in the crowd. The train pulled away.

“I thought we were going on an adventure,” recalls Edith’s childhood friend, Margie Becker. As they passed the majestic Tatra Mountains, the girls sang the Slovak national anthem, unaware of their fate.

Arrival at Auschwitz

Days later, the train reached Auschwitz. The girls, still believing they had arrived at a work camp, were forced into cattle cars. The doors locked from the outside.

After a grueling journey, they were met by men in striped uniforms wielding sticks. “Go quick!” some whispered urgently. They were prisoners themselves. But the girls did not know that yet.

As they marched into the camp, one survivor, Linda Reich, whispered, “That must be the factory where we are going to work.” It was a gas chamber.

The Struggle to Survive

Why did Hitler’s plan to annihilate the Jews begin with 999 young women? According to historian Pavol Mešťan, the Nazis targeted young women first, believing it would prevent future generations of Jews from being born. It was also easier to coerce families into surrendering their daughters rather than their sons.

At Auschwitz, the girls faced starvation, disease, and backbreaking labor. Many perished.

“Some say angels have wings,” Edith reflects. “Mine had feet.” One of the few easier jobs in the camp was sorting confiscated clothing. When Edith’s shoes fell apart, her friend Margie Becker found her another pair. “Shoes could save your life,” Edith says.

Yet even that wasn’t enough to save Lea. In August 1942, the sisters were transferred to Birkenau, where typhus spread rapidly. Despite Edith giving her food to Lea, her sister succumbed to illness.

On December 5, 1942, the Nazis began clearing the camp of typhus-infected prisoners. Lea was among them.

The Death March

By January 1945, the Nazis were retreating. The remaining prisoners, including Edith, were forced on a death march.

“This was the worst,” Edith says. “The snow was red with blood.” Anyone who stumbled was shot. Elsa Rosenthal, her “camp sister,” refused to let Edith fall. They clung to each other for survival.

On January 27, 1945, Auschwitz was liberated. Of the original 999 young women, fewer than 100 survived.

After Auschwitz

The SS later transferred Edith to Ravensbrück and then to a satellite labor camp. When Allied bombers struck, prisoners raided the kitchens while SS guards hid in bunkers.

Finally, on May 8, 1945, the war ended.

Edith and Elsa spent six weeks journeying home to Slovakia. Edith, now gravely ill with tuberculosis from Auschwitz, fought to survive.

Despite her hardships, she never lost hope. In 1948, she married Ladislav Grosman, whose film The Shop on Main Street won an Academy Award in 1965. Though she never became a doctor, she worked as a research biologist in Czechoslovakia and later in Israel. Today, she lives in Toronto, surrounded by her grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

A Final Plea

“You have your little hells but you have your little paradises,” Edith says. “I have had it all here on this Earth.”

“Why are there still wars?” she asks, her voice appearing frail but urgent. “You don’t have a winner in a war. A war is the worst thing that can happen to humanity.”

Sadly, Edith passed away on July 31, 2020, at the age of 96. She left behind an incredible legacy: her daughter and her two daughters and two grandsons…all of us heirs to this “eshet chail,” this one of a kind, incredible fighter, a true Captain who led her troops through the battles, breaches and frays that all our lives are. May she rest in peace and may her memory be forever a blessing.

Sources

https://www.dw.com/en/women-at-auschwitz/a-484586

https://memoirs.azrielifoundation.org/exhibits/sustaining-memories/edith-grosman/

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to tzipporahbatami Cancel reply