Music is not just a series of notes strung together, it is also a tool that can be used for good and bad. Music evokes deep emotions, a bit of music often remains with you in your mind for the rest of your life.

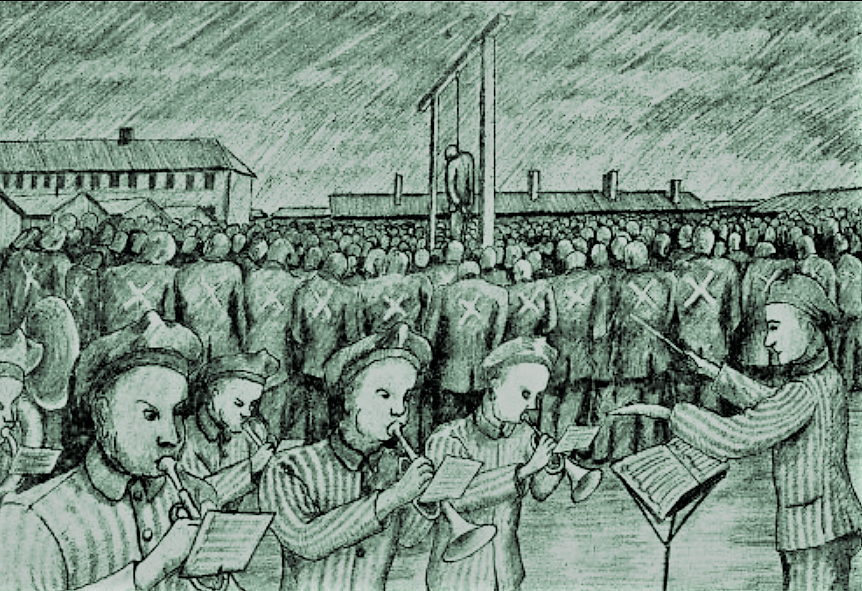

The Nazis used music in the concentration camps, not to make life more pleasant, but as a psychological weapon. Those who survived hearing the music they heard in the camps, often triggered the traumatic memories associated with that bit of music.

Primo Levi, in what is one of the most prominent written accounts of life in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, recounted an incident he witnessed in the infirmary there:

“The beating of the big drums and the cymbals reach us continuously and monotonously, but in this weft the musical phrases weave a pattern only intermittently, according to the caprices of the wind. The tunes are few, a dozen, and the same ones every day, morning and evening: marches and popular songs dear to every German. They lie engraved on our minds and will be the last thing in the Lager that we shall forget: they are the voice of the Lager, the perceptible expression of its geometrical madness, of the resolution of others to annihilate us first as men in order to kill us more slowly afterwards”

I recently lost my best friend. We both loved music and I have noticed that some songs, which we both loved, are no longer a source of pleasure for me they have become a source of grief and pain. However, I know in months and years to come, these songs will once again become a source of joy, they will bring back good memories, For those who were forced to listen to the music in the camps, and maybe some pieces would have been their favourite music before, would now forever be a constant reminder of suffering.

The musicians would feel guilty for being used as an instrument of torture, but they had no choice.

The trumpeter Herman Sachnowitz, among others, described his duties in Monowitz as follows:

“Every morning we played as the inmate work crews departed; the same in the evening, when they returned to the camp . We also played on other occasions, especially during executions, which usually occurred on Sunday afternoons or evenings . Perhaps they intended to drown out the last protests and final curses with music. A grotesque spectacle that had been ordered at the highest level. And the SS men surrounded us with loaded weapons.”

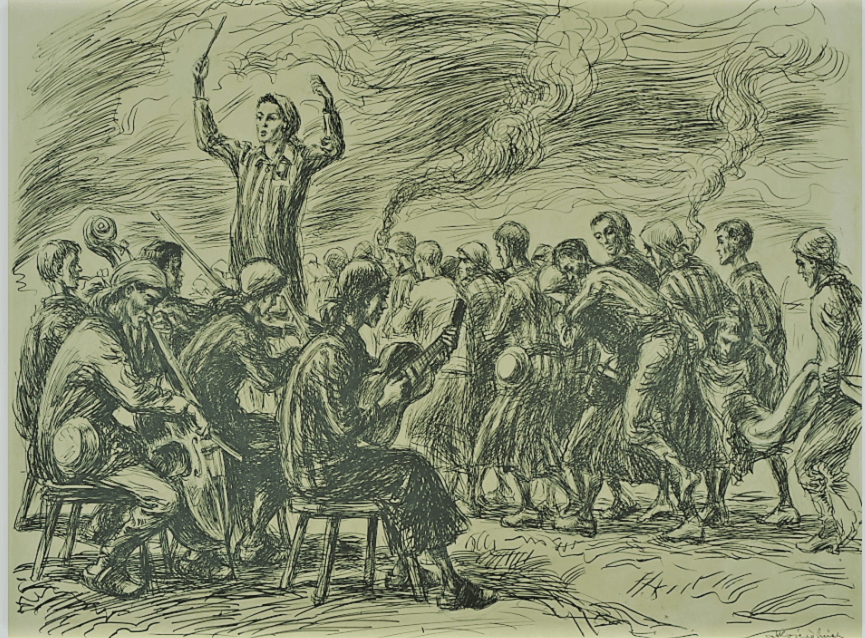

Erika Rothschild recalled being

“driven from the cattle cars and lined up . In addition, a band, consisting of the best inmate musicians, played, and depending on the origins of the transport, they performed Polish, Czech, or Hungarian folk music. The band played, the SS tormented, and there was no time to think , one person was driven into camp, the other to the crematorium.”

Karl Röder, who had been a prisoner in Dachau and Flossenbürg, wrote that singing songs on command was part of the daily routine of camp life:

“We sang in small groups, or one block would sing, or several thousand prisoners all at once. In the latter case, one of us had to conduct because otherwise it would not have been possible to keep time. Keeping time was very important: it had to be crisp, military, and above all loud. After several hours’ singing we were often unable to produce another note.”

The most common musical experience at Buchenwald was SS-organised musical torture, which was a part of every inmate’s daily life. The most ubiquitous form was forced mass singing. As thousands of exhausted inmates gathered for evening roll call, the camp commander would insist that they all sing in unison, on key and loudly. One former inmate recalled, “How could this singing ever go right? We were a chorus of ten thousand men. Even in normal conditions, and if all singers had really known how to sing, it would have required several weeks of training. And how were we to get over the laws of acoustics? The mustering ground measured three hundred paces or more across. Hence the voices of the men on the far side of the ground were bound to reach, Camp Commander Rödl’s ear almost a second later than those of the men near the gate.”

The singing gave the guards a chance to humiliate and arbitrarily punish prisoners.

Early on, the camp leadership organised a competition for the best camp song. Ironically, the winning song, which became the official camp song, Buchenwaldlied (Buchenwald Song), was loved by the prisoners and the guards who forced them to sing it. Set to an energetic march, its rousing chorus focused on the inevitable freedom that awaited them beyond the camp walls. For many of the prisoners, singing the song felt like an act of resistance. One former prisoner said, “The camp leader walked through the camp and whoever wasn’t singing loud enough or at least didn’t open his mouth wide enough while singing, was beaten…but the Buchenwald Song also brought us a little pleasure, for it was our song. When we sang, Then once will come the day when we are free, that was in itself a demonstration, that sometimes even the SS officers noticed, and it could have cost us a meal as punishment.”

Sources

https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/wars-and-memories/violence-war/music-and-torture

https://holocaustmusic.ort.org/places/camps/central-europe/buchenwald/

https://holocaustmusic.ort.org/places/camps/death-camps/auschwitz/camp-orchestras/

https://journals.openedition.org/temoigner/5732?lang=de

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment