Beneath the whispering coastal pine,

Where sand and sorrow softly twine,

They stood with courage, hearts held high,

Though freedom’s cost was to defy.

No trumpet sounded, no fanfare played,

Just silent steps through dune and glade,

Where tyrants feared the truth they bore,

And stilled their voices evermore.

But wind remembers, trees still weep,

The dunes their vigil gently keep—

And in that quiet, hallowed land,

We find their hope still close at hand.

Not gone, not lost, though time moves on—

In Overveen, their light lives strong.

Overveen: A Quiet Village with a Powerful Past

Nestled on the edge of the dunes just west of Haarlem, Overveen may seem like a peaceful, picturesque Dutch village—and it is. With its charming homes, access to the Kennemerduinen National Park, and proximity to the North Sea beaches, Overveen is a beloved place for both locals and visitors seeking tranquility in nature.

But behind its serene beauty lies a powerful and somber history.

During World War II, the dunes near Overveen became the site of tragic executions carried out by the Nazi occupiers. Over 100 resistance fighters, political prisoners, and others who defied the regime were brought here and executed. The sandy hills, now silent, were once the final witness to acts of both cruelty and courage.

In the years after the war, the Erebegraafplaats Bloemendaal (Honorary Cemetery Bloemendaal) was established near Overveen to honor many of these victims. Among them is Hannie Schaft, the young resistance fighter famously known as “the Girl with the Red Hair.” Her story—and those of her fellow fighters—are deeply woven into Dutch memory.

Today, Overveen stands as a place where nature and history meet. A walk through its dunes is not only a journey through breathtaking landscapes but also a quiet tribute to those who gave their lives for freedom. The village reminds us that even the most peaceful places can hold the weight of profound sacrifice.

Whether you come to hike, reflect, or learn, Overveen offers more than just scenery—it offers a story that should never be forgotten.

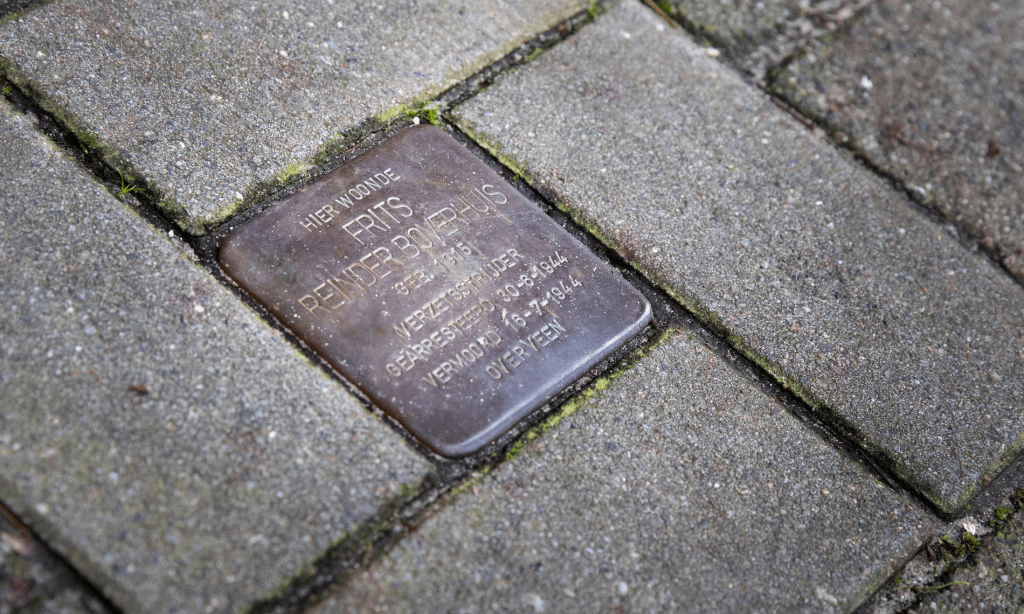

Frits Reinder Boverhuis (Amsterdam, March 26, 1915 – Overveen, July 16, 1944) was a Dutch resistance fighter during World War II.

Resistance work, arrest, and sentencing

Boverhuis was one of the members of the Persoonsbewijzencentrale (PBC – Identity Card Center) around Gerrit van der Veen, which provided false identity papers for Jewish people in hiding and resistance fighters. Boverhuis was the one who pointed out that the Algemeene Landsdrukkerij (National Printing Office) in The Hague had a large stock of materials used to produce identity cards. Together with several PBC members, he carried out a raid on the Landsdrukkerij on April 29, 1944. During the raid, material for 10,000 identity cards was seized.

After the arrest of Van der Veen on May 1, 1944, during a raid on the Huis van Bewaring I (Prison I) at the Weteringschans in Amsterdam, Boverhuis, along with Gerhard Badrian and two others, formed the new leadership of the PBC.

On June 30, 1944, Boverhuis and Badrian were arrested by the Sicherheitspolizei (German Security Police) after a resistance hiding place had been betrayed by Betje Wery. During the arrest, Badrian resisted and was killed.

Boverhuis was executed by firing squad on July 16, 1944, in the dunes near Overveen. Among the group of 14 men executed that day was also Johannes Post. All the victims were buried in a mass grave in the dunes. On November 16, 1945, he was cremated at Driehuis-Westerveld. His urn is located there, in Columbarium III.

Raid on the House of Detention I in Amsterdam (May 1, 1944)

‘Oh God, this was my last chance’ – Johan Limpers and the failed raid on the Weteringschans prison

Johan Limpers was a promising young artist when the war broke out. He threw himself headlong into the resistance, collaborated with Gerrit van der Veen, and became involved in numerous actions by the Council of Resistance. On New Year’s Eve 1943, he participated in a raid on the Weteringschans prison in Amsterdam—where many resistance fighters were being held—but the raid was called off at the last minute. A few months later, he fell into German hands and ended up in the infamous prison himself. Limpers pinned all his hopes on his fellow resistance members, who planned a rescue attempt.

Masked Visitors

It was the night of April 30 to May 1, 1944, when three men walked through the deserted streets of Amsterdam. Near Leidseplein, they stopped right in front of the prison at Kleine-Gartmanplantsoen. At exactly 4:15 a.m., the lock on the entrance door clicked open. Officially called the House of Detention I, the prison was commonly known as the Weteringschans prison. It was one of three facilities used by the Germans in Amsterdam to hold detainees.

The layout revealed a maze of buildings behind the façade. The heart of the complex, opened in 1850, consisted of a cross-shaped structure typical of 19th-century prisons: two intersecting cell wings forming a cross with space for over 200 cells. Over time, various buildings were added: staff housing, a courthouse, an indoor courtyard, washrooms, and an archive. A wartime addition was a wooden barrack reserved for Jewish prisoners—Anne Frank and her family had been held there briefly.

As the door opened, the men quickly slipped inside. Gerard van Welsum, the guard who had opened the lock from inside, was just stepping outside. He collaborated with the resistance and handed the night visitors a full set of keys to the complex.

From nearby doorways and bushes, more men appeared—about eight in total—led by Gerrit van der Veen, a charismatic sculptor turned prominent resistance leader. He tirelessly planned action after action to liberate his imprisoned comrades. The men wore socks over their shoes to stay silent and cloth masks with eyeholes over their faces. Quietly, they crossed the courtyard to the entrance of the main building, knowing that German guards with automatic weapons slept upstairs.

Johan Limpers

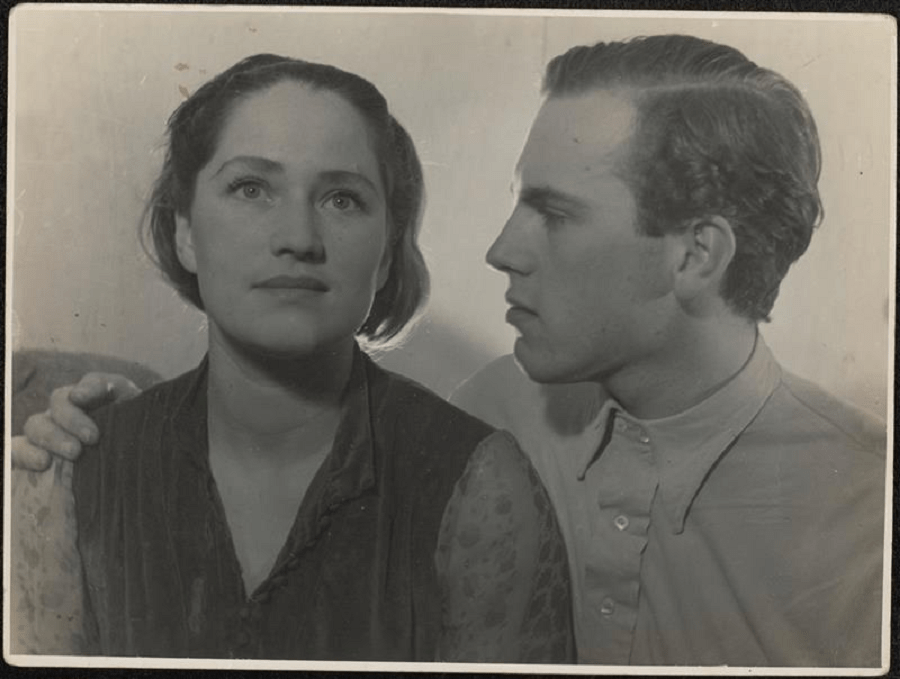

One of the men they hoped to free was Johan Limpers (1915–1944). A talented sculptor and Prix de Rome winner in 1940, Limpers had met Van der Veen at the art academy. He married fellow nominee Katinka van Rood, whom he called “Toosje.”

He saw it as a moral duty to fully commit to the resistance: he hid Jews, forged identity papers, and joined sabotage actions. In March 1944, on his initiative, the Council of Resistance sabotaged the Electro Acid Factory in Amsterdam North.

New Year’s Eve 1943

The May 1 raid had not been the first attempt to enter the Weteringschans. At the end of 1943, Van der Veen planned to approach the prison on New Year’s Eve in a truck disguised as German officers with “arrested” prisoners. The plan failed when the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) found the truck and a weapon inside just before departure. Limpers, dressed in a German uniform, and the rest of the team managed to escape.

Arrest and Prison

Four months later, a second attempt was made. This time, the team gathered at a house on Sarphatistraat, renamed “Muiderschans” during the occupation. But Limpers was no longer present. Weeks earlier, Janrik van Gilse, a key liaison in the communist resistance, was killed in an ambush. On his body, the Germans found a notebook with names—including Limpers, who was arrested shortly after.

Now Limpers found himself imprisoned in the very facility he had tried to break others out of. His cellmate Jo Elsendoorn recalled in his memoirs how Limpers played chess with a fellow prisoner via Morse code tapped through heating pipes. He also whistled music, like Bach’s second suite, and made haunting drawings—among them a self-portrait and nude sketches of his beloved Toosje.

The Raid Fails

As Van der Veen and the others crept through Amsterdam and entered the prison, chaos quickly ensued. A Dutch SS officer had begun bringing a large German shepherd with him during night shifts. Despite warnings to avoid the guardroom where the dog lay, Van der Veen looked through the door window and entered. Jan Brasser followed behind. As they moved silently, the dog raised its head. Van der Veen shot the dog and the sleeping SS officer—breaking the plan’s strict agreement: if one shot was fired, the mission would be aborted.

Panic erupted. Van der Veen and his team fled. In a hallway, SD agents opened fire with machine guns. Most bullets hit the ceiling, creating clouds of chalk dust through which the raiders fled.

Inside and Outside

Prisoners like Limpers heard the commotion—barking dogs, gunfire, shouting. Limpers quickly warned Elsendoorn: “Undress and pretend you’re asleep!” Shortly afterward, SD men burst in, checking which prisoners were dressed and might have known of the plan. Limpers and Elsendoorn narrowly avoided suspicion, but Limpers despaired: “Oh God, this was my last chance.”

Outside, more confusion reigned. Some raiders shot at the gates to distract guards, but others mistook this for German fire and panicked. One member later stated he was shot at by his own comrades.

Aftermath

The consequences were severe. Van der Veen had been shot in the lower back and was taken to a hiding place, but his injuries worsened. Eleven days later, the SD stormed the house where he was hiding. He was imprisoned alongside the very friends he had tried to free. They all sensed what would come next.

On June 10, 1944, Van der Veen wrote to his wife:

“Everything moves so fast—trial this morning, execution soon.”

That same day, Limpers wrote to Toosje:

“To return once more into your arms was the most beautiful thing I could imagine during all this time. Your voice, your warm love, your golden soul have remained sacred to me and I will remember them until the end.”

Hannie Schaft: A Symbol of Courage and Resistance

Hannie Schaft, often called “the Girl with the Red Hair,” is one of the most iconic figures of the Dutch resistance during World War II. Born as Jannetje Johanna Schaft in 1920, she grew up in a time of great political turmoil and upheaval. When Nazi Germany occupied the Netherlands in 1940, Hannie’s life, like that of many others, was irrevocably changed. Instead of fleeing or remaining passive, she chose to stand up against oppression, risking everything for freedom.

Hannie became deeply involved in the resistance movement, engaging in acts of sabotage against the Nazis and helping to protect Jewish families and other victims of persecution. Her bravery was not without great danger; resistance work meant constant risk of arrest, torture, and death. Hannie’s courage and determination made her a key member of the resistance, feared by the occupiers for her daring actions.

Tragically, Hannie Schaft was captured by the Nazis in early 1945. Despite brutal interrogation, she refused to betray her comrades or the cause she so passionately fought for. She was executed shortly before the liberation of the Netherlands, but her legacy endured. Hannie Schaft became a symbol of resistance, sacrifice, and the unyielding spirit of those who fight against injustice.

Today, Hannie’s story inspires generations to stand up for justice and human rights. Her life is a powerful reminder of the difference one person can make, even in the darkest of times.

sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannie_Schaft

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johan_Limpers

https://oorlogsgravenstichting.nl/personen/19017/frits-reinder-boverhuis

https://www.oorlogsbronnen.nl/tijdlijn/47f0a636-57f5-4544-8aac-a2a5ab809f67

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frits_Boverhuis

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment