The athlete Meryll Frost is credited with the phrase, “Behind every great man there’s a great woman,” but that is not what he actually said. What he really said was, “They say behind every great man there’s a woman. While I’m not a great man, there’s a great woman behind me.”

In this blog, I will be exploring the wives of Nazi monsters; they were not great men but evil and twisted. Does this mean we should judge their wives in the same way? I don’t know, I will let everyone decide for themselves.

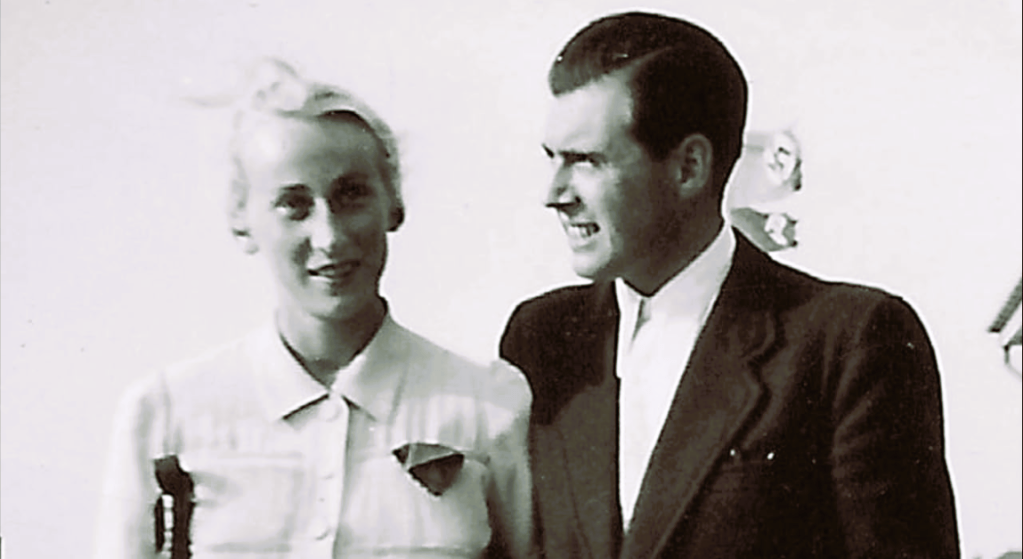

Irene Schönbein

Irene Maria Schönbein, the first wife of Josef Mengele, remains an enigmatic figure in history. While her name is often mentioned in connection with the notorious Nazi doctor known as the “Angel of Death,” the details of her life are largely overshadowed by the horrors committed by her husband. Unlike Mengele, whose crimes against humanity are well-documented, Irene’s life has been shrouded in relative obscurity. This essay delves into the life of Irene Maria Schönbein, exploring her marriage to Mengele, the challenges she faced, and her subsequent efforts to distance herself from her infamous ex-husband.

Irene Maria Schönbein was born in Germany in the early 20th century, although specific details about her early life remain sparse. She was a young woman when she met Josef Mengele, a rising star in the medical and scientific community. At the time, Mengele was not yet the notorious figure he would become. Instead, he was a respected academic with a promising career. Irene and Josef married in 1939, at the outset of World War II. Their marriage seemed typical for the era, with Irene supporting her husband as he pursued his career.

For the first few years of their marriage, Irene and Josef lived relatively quietly. They moved frequently, following Mengele’s work across Germany. However, their relationship began to deteriorate as Mengele’s involvement with the Nazi regime deepened. In 1943, Mengele was assigned to Auschwitz, a posting that would forever change the course of his life and history itself.

Mengele’s assignment to Auschwitz marked a turning point in his relationship with Irene. The distance between them grew, both physically and emotionally. As Mengele became more entrenched in the atrocities at Auschwitz, Irene remained largely uninvolved and isolated from his activities. There is little evidence to suggest that she was aware of the full extent of her husband’s crimes, though it is possible that she harbored suspicions. By this time, the marriage was already under strain, and the couple began to grow apart.

In the aftermath of the war, Irene and Josef Mengele divorced. The exact date of their divorce is not well-documented, but it is believed to have occurred in the mid-to-late 1940s. By then, Mengele was a fugitive, fleeing to South America to escape prosecution for his war crimes. The divorce likely reflected the culmination of years of estrangement, exacerbated by the atrocities Mengele had committed and the consequences he faced.

After her divorce from Josef Mengele, Irene Maria Schönbein effectively disappeared from public view. Little is known about her life following the separation. Unlike many other individuals associated with high-ranking Nazis, Irene did not become a public figure, nor did she engage in activities that would draw attention to herself. This lack of information suggests that she may have sought to distance herself from the notoriety of her former husband and the stigma attached to his name.

One plausible interpretation is that Irene sought to rebuild her life away from the shadow of Mengele’s legacy. Given the widespread condemnation of Nazi war criminals after the war, it is likely that Irene faced significant challenges in redefining her identity. In a world coming to terms with the horrors of the Holocaust, being associated with Josef Mengele would have been a heavy burden to bear.

Magda Goebbels

In the grand halls of the Reich Chancellery, where ambition once roared with the echoes of conquest, silence had fallen. Berlin was in ruins, the heart of the Third Reich bleeding as Allied forces closed in. Inside the Führerbunker, deep beneath the shattered city, Magda Goebbels, wife of Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, made a decision that would forever stain her legacy.

Magda Goebbels was born Johanna Maria Magdalena Ritschel on November 11, 1901, in Berlin. Her early life was marked by privilege and comfort. Raised in a well-to-do family, she enjoyed the best education and opportunities society could offer a young woman of her status. However, her childhood was also marked by instability; her parents divorced when she was young, and her mother’s subsequent remarriage introduced her to the Jewish businessman Richard Friedländer, whom she would come to regard as a father figure.

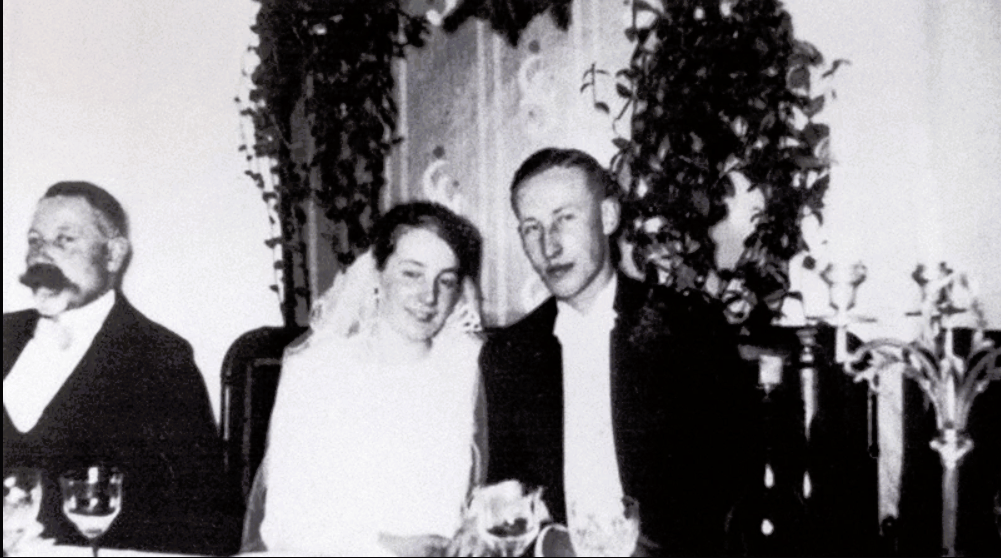

Magda’s first marriage was to Günther Quandt, a wealthy industrialist—nearly two decades her senior. (BMW is one of the companies)The union produced a son, Harald, but it was marked by emotional distance. Magda, restless and ambitious, found herself dissatisfied with the life of a wealthy housewife. Her growing interest in politics and national affairs led her to the burgeoning Nazi Party, where she met Joseph Goebbels.

Magda’s marriage to Joseph Goebbels in 1931 marked the beginning of her deep involvement in the Nazi movement. Goebbels, who had risen to become Hitler’s chief propagandist, was captivated by Magda’s beauty, intelligence, and unwavering loyalty to the Nazi cause. Together, they became one of the most prominent couples in the Third Reich, often seen by Hitler’s side at public events. Magda was not merely a political wife; she was deeply committed to the ideals of National Socialism, viewing Adolf Hitler as a near-divine figure who could restore Germany’s former glory.

The Goebbels had six children, whom Magda proudly presented as the perfect Aryan family. The children were often photographed with Hitler, who was their godfather. To the outside world, the Goebbels family represented the ideal Nazi household, a symbol of the future the Third Reich promised. Behind closed doors, however, the marriage was troubled. Joseph Goebbels was a notorious philanderer, and his infidelities caused Magda great pain. Despite the personal turmoil, she remained loyal to her husband and even more so to the Führer.

As the war turned against Germany, Magda’s world began to unravel. The defeats on the Eastern Front, the relentless Allied bombing campaigns, and the advancing Soviet army marked the beginning of the end for the Nazi regime. By 1945, Berlin was a city under siege, its streets filled with rubble and despair.

Magda and her children moved into the Führerbunker in late April 1945 as the Soviet Red Army closed in on Berlin. Inside the bunker, there was a sense of impending doom. Adolf Hitler had already resigned himself to defeat, and those closest to him were preparing for the end. Magda, who had always been fiercely loyal to Hitler, made a fateful decision. If the Reich was to die, her family would die with it.

On April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler committed suicide, leaving his inner circle to face the consequences of their actions. For Magda, this was the ultimate betrayal of the vision she had dedicated her life to. Without Hitler, the world seemed devoid of meaning. That evening, she confided in her husband, Joseph, her plan to end the lives of their six children. For her, they represented the pure future of the Aryan race—a future that could not exist without National Socialism.

Joseph Goebbels, who had always been as devoted to Hitler as his wife, agreed. On May 1, 1945, Magda, with the help of the family’s doctor, administered poison to each of her children as they slept. Helga, Hilde, Helmut, Holdine, Hedwig, and Heidrun—aged between four and twelve—were killed in their beds, unaware of the world’s collapse around them. After ensuring their deaths, Magda and Joseph Goebbels took their own lives later that evening.

Magda Goebbels’ actions on that final day have been the subject of horror and fascination for decades. Some view her as a fanatic, so profoundly indoctrinated by Nazi ideology that she saw no life for her children beyond the Reich. Others see her as a tragic figure, a woman who, having invested everything in a monstrous regime, could not bear to live without it.

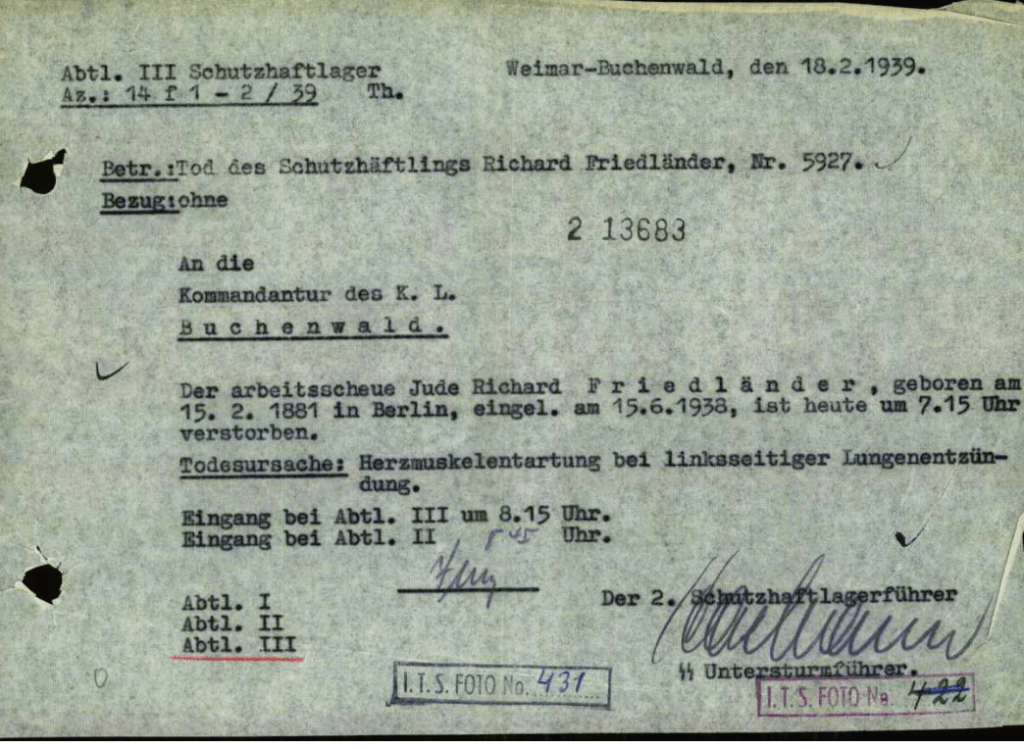

Magda’s stepfather, Richard Friedländer, who had raised her since she was 7, was Jewish. Friedländer was born to a wealthy Jewish Berlin merchant family. After attending junior and high schools, he was employed as a merchant in Brussels. In 1908, he married Auguste Behrend, who was divorced from her first husband, Oskar Ritschel, and was the mother of Magda. Magda was enrolled at the Ursuline Convent in Vilvoorde. Friedländer eventually adopted Magda. In 2016, it was reported that Friedländer may have been Magda’s biological father, as stated in his residency card, found in the Berlin archives by writer and historian Oliver Hilmes. However, Magda’s adoption may have been required for her parents’ delayed marriage to update the girl’s “illegitimate child” status. Friedlander died in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1939; his daughter did not attempt to help him.

–––

Emmy Göring

Emmy Sonnemann Goering, the wife of Hermann Goering, is a figure who played a significant role within the social and cultural framework of Nazi Germany. Born on March 24, 1893, in Hamburg, Germany, Emmy Sonnemann was an actress before she married Hermann Goering, a leading member of the Nazi regime. Her life offers a glimpse into the personal dynamics of the Third Reich and the complicity of individuals who, while not directly involved in the political or military operations, still contributed to the cultural and social legitimacy of the Nazi state.

Emmy Sonnemann was born into a middle-class family. Her father was a successful businessman, which afforded her a comfortable upbringing. From a young age, Emmy was drawn to the arts, in particular acting. She pursued a career in theater, joining various theater companies across Germany. By the early 1920s, Emmy had established herself as a respected actress, performing in several well-known theaters. Although she never reached the level of international fame, she was well-regarded in German theatrical circles.

Emmy Sonnemann’s life took a dramatic turn when she met Hermann Goering in 1934. Goering, a World War I fighter ace, was a prominent figure in Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime, serving as the head of the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) and holding significant political power. After a brief courtship, the couple married on April 10, 1935, in a lavish ceremony that was one of the most prominent social events of the Nazi era. Adolf Hitler served as a witness, underscoring the political significance of the marriage. The wedding was broadcast on German radio and symbolized the union of high society with the Nazi elite.

As the wife of Hermann Goering, Emmy Goering assumed a role akin to that of the “First Lady” of the Third Reich, especially since Hitler was unmarried. She became a prominent social figure in Nazi Germany, hosting extravagant parties and gatherings at the Goering estate, Carinhall. These events were often attended by the upper echelons of the Nazi leadership and served as a platform for Nazi propaganda and the display of Aryan culture. Emmy was a staunch supporter of her husband’s political career and was actively involved in promoting the cultural policies of the regime, which included the suppression of “degenerate” art and the promotion of works that aligned with Nazi ideology.

Emmy’s influence extended beyond her social duties. She was awarded the honorary title of “First Lady of the Third Reich” by Hitler, reflecting her symbolic importance to the regime. Her marriage to Goering provided her with privileges and luxuries that few could imagine during a time when many Germans were suffering under the economic strains of war. She used her position to further her personal interests, particularly in the arts, where she advocated for traditional German theater, which aligned with Nazi ideals.

With the fall of the Third Reich in 1945, Emmy Goering’s life of privilege came to an abrupt end. Hermann Goering was arrested and put on trial at Nuremberg for war crimes, where he was convicted and sentenced to death. Before his execution, he committed suicide by ingesting cyanide. Emmy Goering was arrested by Allied forces and underwent a denazification trial. In 1948, she was classified as a “follower” (Mitläufer) of the Nazi regime and was sentenced to a year in a labor camp. Her assets were confiscated, and she was banned from working in theater.

After her release, Emmy Goering lived a relatively quiet life in obscurity, far removed from the grandeur she once enjoyed. She published her memoirs in 1948, titled My Life with Goering, in which she attempted to downplay her involvement with the Nazi regime and portray herself as a passive bystander. She died in Munich on June 8, 1973, largely forgotten by the world.

Lina Heydrich

Lina Heydrich, born Lina Mathilde von Osten on June 14, 1911, was the wife of Reinhard Heydrich, one of the most notorious figures in Nazi Germany. As the spouse of the man who was instrumental in planning and executing the Holocaust, Lina’s life and actions offer a disturbing glimpse into the complicity of those who supported and sustained the Nazi regime. Her story is one of ambition, ideology, and a chilling loyalty to one of the darkest causes in human history.

Lina von Osten was born on Fehmarn, a small island in the Baltic Sea, into a family with nationalist and anti-Semitic views, which were not uncommon in post-World War I Germany. This environment shaped her political beliefs from an early age. Lina was a fervent supporter of the Nazi Party, joining the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) in the late 1920s. Her ideological solid commitment to National Socialism would later play a crucial role in her marriage.

In December 1930, Lina met Reinhard Heydrich, a young naval officer with a troubled career. They married on December 26, 1931, shortly after Heydrich was dismissed from the navy due to a scandal. It was Lina who urged Heydrich to join the SS (Schutzstaffel), a decision that would set the course for both their lives. Through her connections and unwavering support, she helped Heydrich rise through the ranks of the SS, eventually becoming one of Heinrich Himmler’s most trusted deputies.

Lina Heydrich was not a passive wife; she was deeply involved in her husband’s career and shared his ideological zeal. She was a staunch advocate of Nazi principles, especially their anti-Semitic and nationalist tenets. Lina was well aware of Heydrich’s role in the systematic persecution of Jews and other minorities, and she fully supported his actions. She reveled in the power and prestige that came with being married to one of the Third Reich’s most feared leaders, earning herself the nickname “the First Lady of the SS.”

During World War II, Lina managed the family’s estate in Panenské Břežany, near Prague, while her husband orchestrated the “Final Solution.” Reinhard Heydrich was the principal architect of the Wannsee Conference, where the plan for the extermination of European Jews was formalized. Although there is no evidence that Lina directly participated in these operations, her unwavering support for her husband’s work and her enthusiastic embrace of Nazi ideology make her complicit in the regime’s crimes.

On May 27, 1942, Reinhard Heydrich was mortally wounded in an assassination attempt by Czechoslovak resistance fighters in Prague. He died a few days later, on June 4, 1942. Lina was devastated by her husband’s death and sought revenge. In retaliation for the assassination, the Nazis carried out the Lidice massacre, where the village of Lidice was destroyed and its male population was executed. Lina later expressed no remorse for these events, maintaining that the destruction of Lidice was justified.

After Heydrich’s death, Lina continued to live a life of privilege for the remainder of the war, raising her four children. As the war drew to a close, she fled to the Bavarian Alps, where she was arrested by Allied forces. Although she was interrogated, Lina was never formally charged with any crimes. After her release, she faced denazification proceedings but was ultimately classified as a “lesser offender,” allowing her to escape significant punishment.

In the post-war years, Lina Heydrich faced a life of obscurity and financial difficulty. She published a memoir in 1976, titled Leben mit einem Kriegsverbrecher (Living with a War Criminal), in which she portrayed herself as a devoted wife and loyal Nazi, steadfastly defending her husband’s actions and legacy. Lina never recanted her Nazi beliefs, and she remained unapologetic for her role in the regime.

Lina Heydrich died on August 14, 1985, in Fehmarn, Germany, largely unrepentant and untouched by the justice that befell many of her husband’s colleagues. Her life represents the broader narrative of those who, while not directly involved in the Nazi leadership, contributed to the regime’s ideological and social structure. She was a fervent believer in National Socialism, and her actions and words demonstrate the dangers of fanaticism and blind loyalty.

Eva Braun

Eva Braun is a figure often overshadowed by the monstrous legacy of her partner, Adolf Hitler. Born on February 6, 1912, in Munich, Germany, Braun lived most of her life in the shadow of the Nazi dictator, with whom she shared a long, secretive relationship. Her role as Hitler’s companion and later as his wife in the final days of World War II raises complex questions about complicity, loyalty, and the human capacity to turn a blind eye to atrocity. Though often portrayed as a naive and apolitical woman, Braun’s life and choices provide a revealing lens into the personal dynamics of one of history’s most infamous regimes.

Eva Braun was born into a middle-class Catholic family. Her father was a schoolteacher, and her mother was a seamstress. Raised in a relatively conservative environment, Braun led a typical life for a young woman of her background until she met Adolf Hitler. At the age of 17, while working as a sales assistant and model for Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s personal photographer, Braun encountered Hitler, who was 23 years her senior. Their relationship developed quickly, despite Hitler’s initial reluctance to enter into a public romantic relationship due to his belief that it would damage his image as a leader solely dedicated to Germany.

By the early 1930s, Braun had become a regular presence in Hitler’s life, although she remained hidden from public view. Hitler kept their relationship secret for many years, believing that his image as a bachelor was politically advantageous. Braun, however, was devoted to Hitler and accepted this arrangement despite the personal sacrifices it entailed. Their relationship was marked by long periods of separation and secrecy, during which Braun lived a relatively isolated life, removed from the political sphere of the Third Reich.

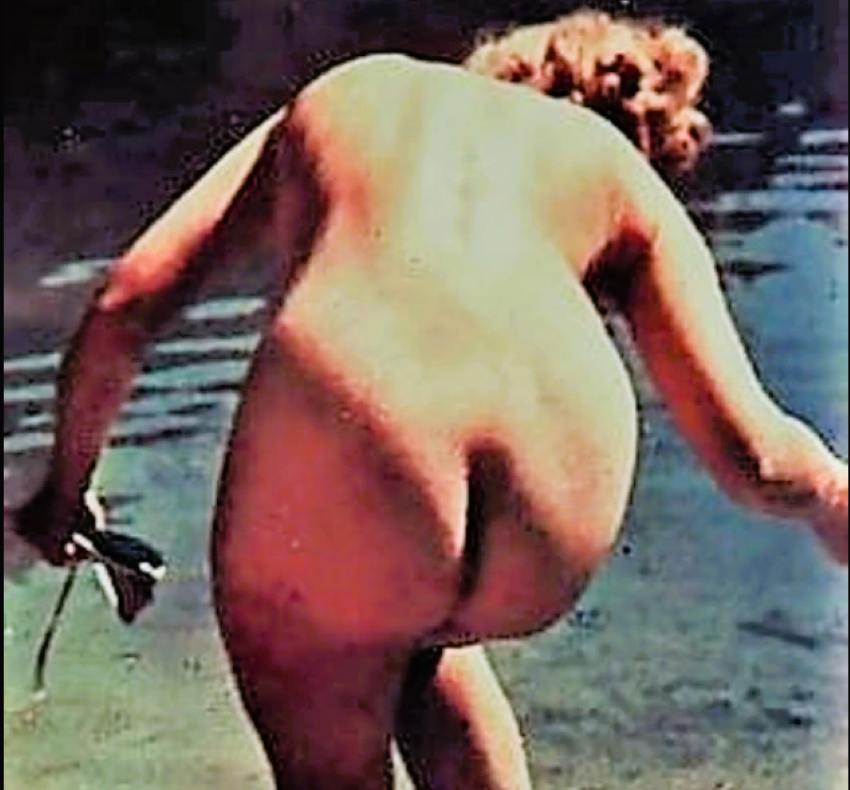

Eva Braun spent much of her time at the Berghof, Hitler’s mountain retreat in the Bavarian Alps. The Berghof became her sanctuary, where she indulged in photography, fashion, and sports like skiing and swimming. Her photographs and home movies from this period provide a rare glimpse into the private life of the Nazi elite, portraying a world far removed from the horrors being inflicted on Europe by the regime. Despite her proximity to Hitler, Braun was kept largely ignorant of the details of his political and military decisions, at least officially. However, it is unlikely that she was completely unaware of the atrocities being committed under Hitler’s orders, given her close connection to him and her access to the inner circle of Nazi leaders.

Braun’s role at the Berghof was primarily domestic, organizing social events and attending to Hitler’s personal needs. She was not involved in the political machinations of the Nazi leadership. Yet, her relationship with Hitler provided her with a life of privilege and luxury. Braun’s existence was paradoxical; she was both central and peripheral to the Nazi regime—central in her influence over Hitler’s private life but peripheral in the grand scheme of the regime’s operations.

As the war turned against Germany, Braun’s loyalty to Hitler never wavered. She joined him in the Führerbunker in Berlin in the final days of the war. On April 29, 1945, as Soviet forces closed in on the city, Hitler and Braun were married in a brief civil ceremony. The following day, on April 30, 1945, the couple committed suicide together—Hitler by gunshot and Braun by cyanide—thus ending their lives as Berlin fell to the Allies.

Their deaths were a final act of loyalty to the Nazi cause, with Braun remaining by Hitler’s side until the very end. In her suicide note, Braun expressed no regret for her actions or her relationship with Hitler, instead showing a fatalistic acceptance of their shared fate. Her marriage to Hitler, while short-lived, was symbolically significant, marking her as one of the few people who remained loyal to him even as his regime crumbled.

Eva Braun’s legacy is a complex and controversial one. She has often been depicted as a naive, apolitical woman who was more interested in fashion, photography, and her own personal life than in the brutal realities of the regime her partner led. However, this characterization fails to fully capture the moral ambiguity of her position. While it is true that Braun was not a decision-maker within the Nazi regime, her voluntary association with Hitler and her acceptance of the benefits that came with it implicate her in the broader moral culpability of the Nazi leadership.

Some historians argue that Braun was complicit in the sense that she chose to remain with Hitler despite knowing at least some of the crimes he was committing. Others suggest that she was essentially a victim of circumstance, a woman who became emotionally dependent on a powerful and manipulative man. Regardless of her exact role, Eva Braun’s life raises important questions about the nature of complicity, the power dynamics in relationships, and the ways in which ordinary individuals can become entangled in the machinery of evil.

Sources

https://www.wikitree.com/photo/png/Schoenbein-59-1

https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LC76-J1L/irene-maria-sch%C3%B6nbein-1917

https://www.history.co.uk/biographies/magda-goebbels

https://www.timesofisrael.com/goebbels-wife-had-jewish-father-new-document-shows/

https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Emmy_G%C3%B6ring

https://www.geni.com/people/Emmy-G%C3%B6ring-Sonnemann/6000000007709404452

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Eva-Braun

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/belle-third-reich-eva-braun

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment