The defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945 left the world not only devastated by years of total war but also confronted with the unparalleled crimes of the Holocaust. Among the many perpetrators brought before courts in the immediate aftermath was Amon Leopold Göth, the Austrian SS officer who had served as commandant of the Płaszów concentration camp near Kraków. His execution in 1946 symbolized not only the retribution of justice but also the international effort to confront the human cost of Nazi barbarity. The trial and death of Göth stand as one of the early and significant episodes in the legal and moral reckoning with crimes against humanity.

Göth and His Crimes

Born in Vienna in 1908, Göth joined the Austrian Nazi Party in the early 1930s and quickly found his way into the ranks of the SS. His reputation for ruthlessness brought him to occupied Poland during the war, where he was appointed commandant of the newly established Płaszów labor camp in 1943. Initially intended as a temporary holding camp, Płaszów expanded into a major concentration camp where tens of thousands of Jews, Poles, and other prisoners were subjected to forced labor, starvation, and systematic murder.

Göth’s cruelty was notorious even among the SS. Survivors testified that he frequently shot prisoners at random, sometimes from the balcony of his villa overlooking the camp.

He also oversaw the liquidation of the Kraków and Tarnów ghettos, operations that resulted in mass executions and deportations to extermination camps. By the time he was relieved of command in 1944—partly due to charges of corruption and theft of Jewish property—Göth had already earned a reputation as one of the most sadistic figures in the Nazi camp system.

The Trial in Kraków

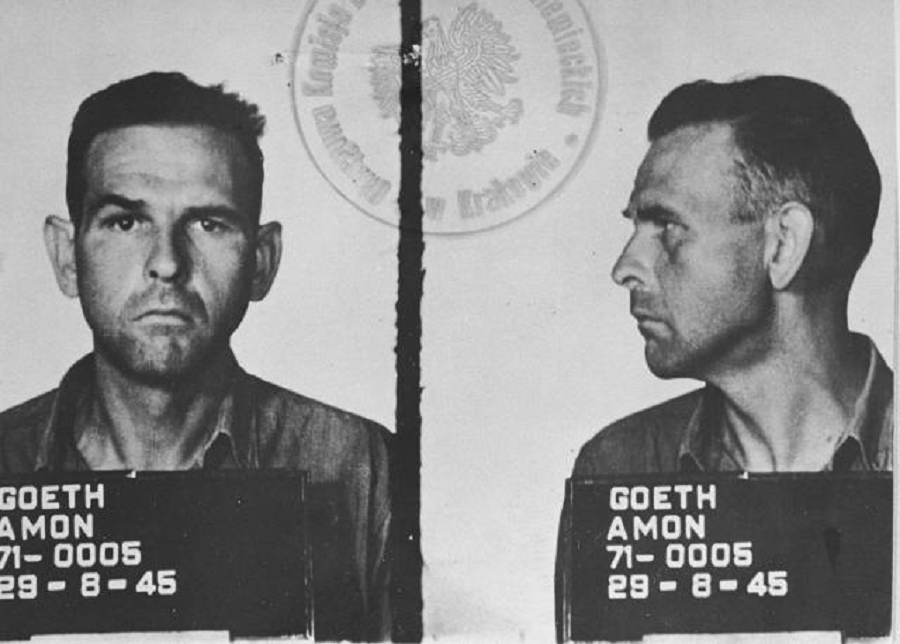

Göth was captured by American forces in May 1945 and was soon extradited to Poland, where his crimes had been committed. Unlike many top Nazi leaders tried before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, Göth faced justice before the Supreme National Tribunal of Poland. This court was established in 1946 to prosecute German war criminals whose offenses had been carried out on Polish soil, reflecting the determination of local authorities to assert their role in the postwar reckoning.

The trial, which took place in Kraków between August and September 1946, relied heavily on the testimony of survivors and documentary evidence. Witnesses described Göth’s brutality in detail: his arbitrary executions, his role in ghetto liquidations, and his direct involvement in killings at Płaszów. Unlike higher-ranking Nazi officials who claimed ignorance of specific atrocities, Göth’s personal participation in acts of violence left little doubt about his guilt. His defense—that he was merely following orders—was rejected as untenable in light of his excessive zeal and cruelty. The Tribunal convicted him of war crimes and crimes against humanity, sentencing him to death on September 5, 1946.

The Execution at Montelupich Prison

Amon Göth’s execution took place on September 13, 1946, at Montelupich Prison in Kraków, a site notorious during the war as a Gestapo detention and execution center. The symbolism of executing Göth in a place once used by the Nazi regime to terrorize Poles was deliberate, underscoring both justice and historical irony. Unlike the Nuremberg executions, which were carried out in secrecy, Göth’s hanging was conducted in front of witnesses. Reports suggest that the execution was not entirely smooth—the initial drop failed, requiring officials to complete the process—but the outcome was the same: Göth was hanged, bringing an end to one of the Holocaust’s most infamous perpetrators.

Context and Significance

The execution of Amon Göth must be understood within the broader context of postwar justice. The Nuremberg Trials of 1945–1946 established the precedent for prosecuting crimes against humanity, but thousands of other Nazi officials and collaborators were tried in national courts across Europe. Göth’s case exemplifies the decentralized but coordinated efforts of Allied and local authorities to punish individuals directly responsible for atrocities. Unlike the highly political trials of major Nazi leaders, Göth’s trial was local, focused, and closely tied to the testimonies of survivors who had witnessed his crimes firsthand.

Göth’s execution also carried symbolic weight. As commandant of Płaszów, his cruelty became a microcosm of the Holocaust in occupied Poland, where extermination and forced labor camps operated on a massive scale. By trying and executing him in Kraków, the Polish court asserted the right of victims’ communities to seek justice, giving survivors a voice in the process. His death thus reinforced the principle of individual accountability: that no official, regardless of rank or orders received, could escape responsibility for crimes of genocide and mass murder.

Legacy

In the decades since, Amon Göth has remained a figure of infamy, especially following his portrayal in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993). The film, based on the true story of Oskar Schindler’s rescue of Jews from Płaszów, immortalized Göth as a symbol of unrestrained sadism and moral corruption. While cinematic portrayals inevitably dramatize reality, they reflect the documented cruelty for which Göth was executed.

More importantly, the trial and execution of Amon Göth underscore a broader historical lesson. They highlight the necessity of legal reckoning after atrocity, the role of national courts alongside international tribunals, and the enduring imperative to hold individuals accountable for crimes that shock the conscience of humanity. Though no execution could ever restore the lives lost at Płaszów, Göth’s death was a declaration that the world would not simply move on without demanding justice.

The execution of Amon Göth in September 1946 was more than the punishment of one man; it was an act of justice that embodied the world’s attempt to respond to the enormity of the Holocaust. His crimes, carried out with a chilling blend of authority and sadism, made him an emblem of Nazi cruelty. His trial in Kraków, based on survivor testimony and local memory, ensured that the voices of victims were central to the pursuit of justice. His execution, though a single event in a broader postwar reckoning, remains a reminder that accountability, however imperfect, is essential in the aftermath of atrocity. The rope that ended Göth’s life symbolized not vengeance but the moral necessity of confronting crimes that could never be forgotten.

Ordinarily, Goeth’s story might have ended with his execution, but he left behind a wife and two children—as well as a daughter by his mistress. Decades later, one of his grandchildren would uncover this hidden legacy, a grim skeleton in her genetic closet.

Ruth Irene Kalder (born in Gleiwitz, Germany—now Gliwice, Poland) was a German woman best known for her relationship with Amon Goeth, the SS officer and commandant of the Płaszów concentration camp during World War II.

Kalder originally pursued a career in cosmetics and acting before working as a secretary for the Wehrmacht in Kraków. While living there, she became acquainted with businessman Oskar Schindler, later renowned for saving Jewish lives during the Holocaust. Schindler introduced her to Goeth, hoping to secure Jewish forced laborers for his factory through this connection.

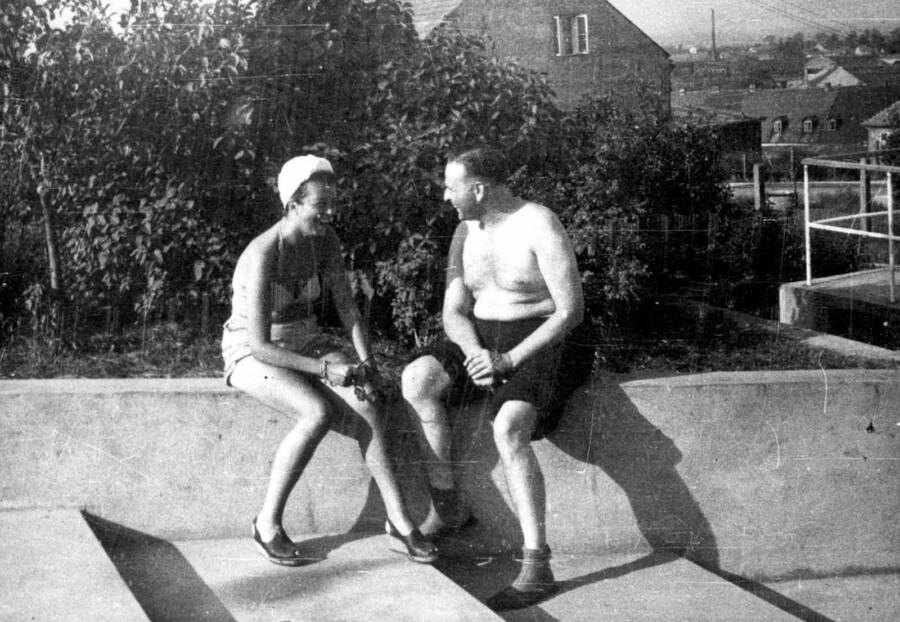

Despite Goeth’s marital status—he had been married twice and was still legally bound to a wife in Germany with three children—Kalder developed a close attachment to him. She became his constant companion and was even regarded as his fiancée. Known by the nickname “Majola,” she lived with Goeth in his villa near the Płaszów camp.

Survivors later recalled Kalder as deeply infatuated with Goeth and seemingly indifferent to the atrocities committed at the camp. She reportedly spent her days on beauty treatments and leisure, often playing loud music to drown out the sounds of executions and gunfire.

In April 1945, after the U.S. Army captured Bad Tölz, Goeth was identified as a wanted war criminal and handed over to Soviet authorities.

After Amon Goeth’s execution in 1946, Ruth Irene Kalder was left devastated. Despite his atrocities, she remained devoted to him, even adopting his surname once she learned of his death by hanging. The year before, in 1945, she had given birth to their daughter, Monika Hertwig.

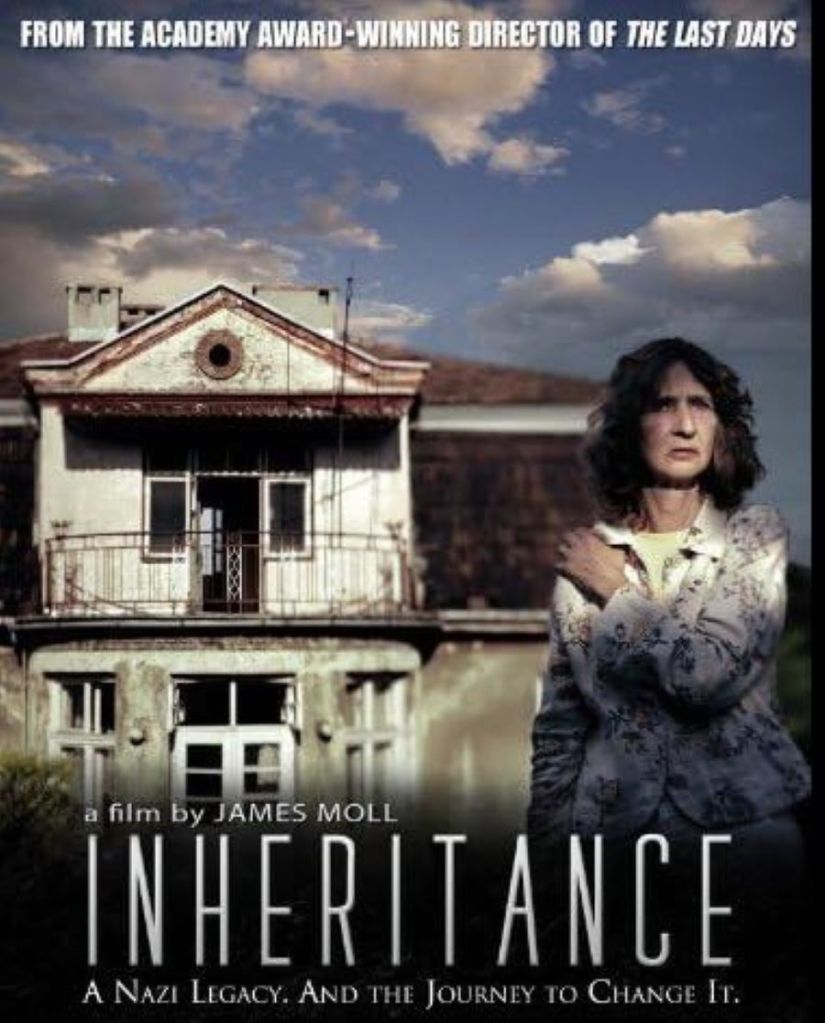

Decades later, in 2002, Hertwig published her memoir I Do Have to Love My Father, Don’t I?, recounting the struggles of growing up with a mother who idealized Goeth. In 2006, she appeared in the documentary Inheritance, where she confronted the legacy of her father’s crimes and her own journey toward reckoning with his history.

In 2008, a Black German woman named Jennifer Teege was browsing in a Hamburg library when she came across a copy of Monika Hertwig’s memoir. As she leafed through the pages, a shocking realization took hold.

“At the end, the author summed up some details about the woman on the cover and her family, and I realised they were a perfect match with what I knew about my own biological family,” Teege later wrote for the BBC. “So, at that point, I understood that this was a book about my family history.”

Teege had grown up largely apart from her mother, spending her early years in a children’s home before being adopted by a foster family. Though she saw her biological mother occasionally until the age of seven, their relationship was distant. That mother was Monika Hertwig—making Amon Goeth, the commandant of Płaszów, Teege’s grandfather.

“I slowly started to understand the impact of what I had read. Growing up as an adopted child, I knew almost nothing about my past—only fragments. To suddenly be confronted with something like this was overwhelming,” Teege recalled. “It took weeks, even a month, before I began to recover.”

In time, Teege transformed her shock into reflection. She wrote her own book, My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me, grappling not only with her personal discovery but also with broader questions about family, legacy, and identity.

“I have tried not to leave the past behind, but to place it where it belongs,” she explained. “That means not ignoring it, but also not letting it overshadow my life. I am not a reflection of this part of my family story, but I remain deeply connected to it. My task is to find a way to integrate it into my life.”

sources

https://allthatsinteresting.com/amon-goeth

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/138133205/ruth_irene-goeth

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0827507/?ref_=mv_close

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amon_G%C3%B6th

https://www.holocausthistoricalsociety.org.uk/contents/naziseasternempire/plaszow.html

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Amon-Goth

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/photo/amon-goeth-front-left-commandant-of-the-plaszow-camp-under-escort-to-the-courthouse-in-krakow-for-sentencing#https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.18574/nyu/9781479804375.003.0008/html?lang=en&srsltid=AfmBOorwFQCG-qCn2mgPaJ6bo3A7d6lnKGR8PjuyFPAwdtIvadIUIM1c

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment