Many European countries had an equivalent of the NSDAP(Nazi) party, the Dutch National Socialist party was the NSB. It may be hard to believe nowadays but not every National Socialist party started off as an anti-Semitic party, as was the case with the NSB.

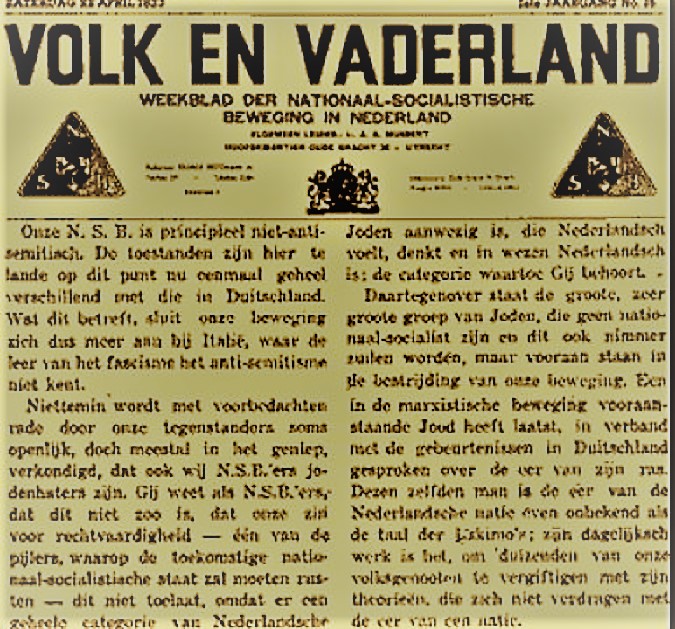

The NSB even had Jewish members, and the party leader ,Anton Mussert, emphasized in the party’s news paper,Volk en Vaderland(people and Fatherland) that the NSB was not an anti-Semitic party and Jews were welcome.

He also wanted to make it clear that the NSB was nothing like the German NSDAP,it felt more aligned with the Italian Fascist party.

He claimed that the Jews would always be an integral part of the future of the Netherlands and they had nothing to be worried about. However that prediction and promise became null and void the minute the Nazis took power in the Netherlands.

Although initially the Jews who had been active members of the NSB were excluded from deportation.

On 27 February 1943, eight or nine Jews (sources vary slightly) — sometimes referred to as the “Mussert Jews” due to their prior membership in the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB, the Dutch Nazi-aligned party) before its policies became openly antisemitic — moved into Villa Bouchina.

Among them were families such as the Jo Spier family, including their children, as well as individuals like Abraham Spetter, Paul Drukker, and Kaatje van Lunenburg-Groen.

It is important to note that these residents were not subject to a strict guarding regime: there were no posted guards, only a cook and a cleaning lady. This suggests that their stay at Villa Bouchina was not meant as typical incarceration, but rather a form of “privileged containment” under the supervision of specific authorities — possibly intended to encourage other Jews to surrender under the promise (or threat) of similar protection.

Villa Bouchina became available after Rev. J. Th. Meesters, the resident pastor, was arrested for his involvement in the Dutch resistance. He was taken to the Amersfoort transit camp on September 11, 1942, and executed on October 15 of the same year. During the period when the villa housed the nine Jews, the household employed a cleaning woman and a cook, but there were no guards stationed at the property.

Although these individuals had been expelled from the NSB, their earlier affiliation caused them to be regarded as traitors. On April 21, 1943, they were deported to the Theresienstadt camp. Their stay at Villa Bouchina was not due to any particular interest from the German authorities or the exiled Dutch government, but because they were under the personal protection of Anton Mussert. Mussert himself was executed in 1946.

The environment in Villa Bouchina was ambiguous: residents enjoyed more freedom than in typical internment camps and faced no overt physical restraints. Nevertheless, their security was precarious. They existed in a liminal state — neither fully free nor formally imprisoned in a concentration camp — yet remained under the control of the Nazi apparatus.

Given the circumstances, with no guards and only minimal staff, daily life may have resembled that of a small, secluded household marked by anxious uncertainty rather than the harsh conditions of a conventional prison. Still, the residents were fully aware that their fate rested entirely on the decisions of the occupying authorities. The so-called “protection” they received was fragile and temporary.

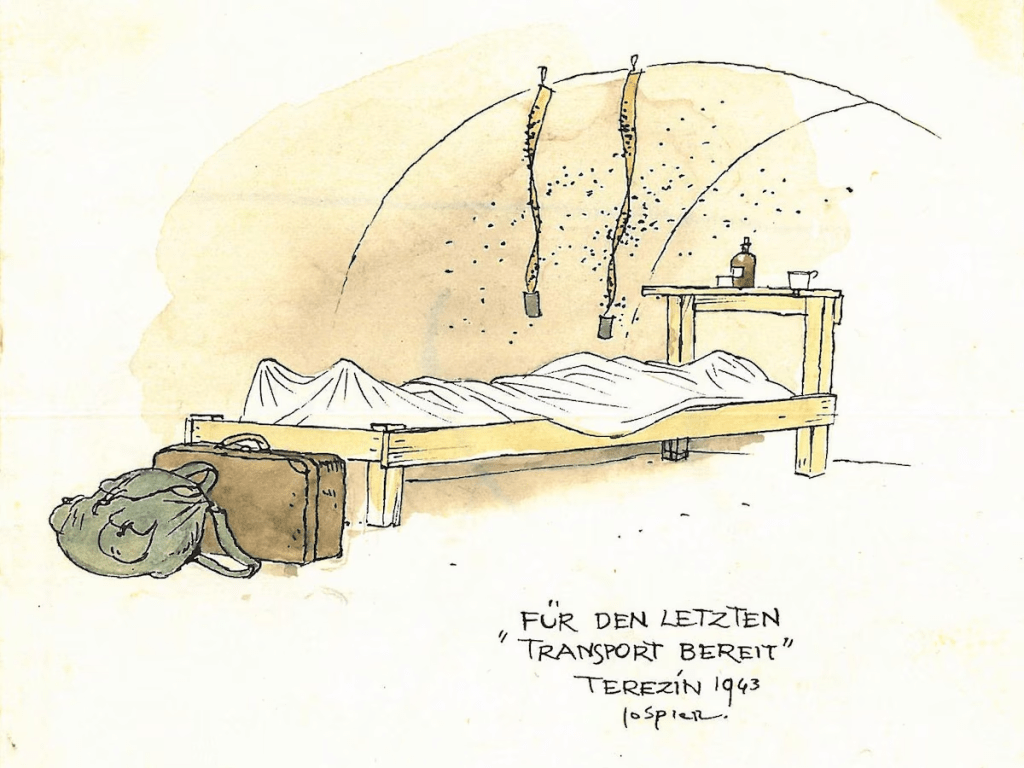

On 21 April 1943, just under two months after their arrival, the residents of Villa Bouchina were deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp (Terezín), located in what was then occupied Czechoslovakia.

From there, their fates diverged. Some, including the Spier family, survived the war. Others, such as Paul Drukker, were later deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz concentration camp, where he perished. Notably, among the internees was Jo Spier, a recognized artist.

Historical Significance and Interpretations

The story of Villa Bouchina illustrates one of the more insidious aspects of Nazi persecution: the use of bureaucratic manipulation, social hierarchy, and false promises of “protection” to control Jewish populations. Along with other locations such as De Schaffelaar and De Biezen in Barneveld, Villa Bouchina demonstrates that not all Jews during the occupation were treated identically; some were temporarily singled out for “special housing.”

Yet this apparent privilege was deeply conditional and coercive. Nothing guaranteed survival, and many residents were ultimately deported to concentration camps. Historians debate how to interpret cases like Villa Bouchina. The notion of “privileged Jews” — sometimes associated with schemes like Plan Frederiks — reveals how occupiers exploited hope, fear, and social divisions as tools of oppression. In some cases, these arrangements may have pressured victims into revealing themselves rather than going into hiding, turning “privileged internment” into a trap. The villa’s brief function — lasting less than two months — underscores the fragility and impermanence of such protections.

Villa Bouchina also raises broader moral and historical questions regarding complicity, collaboration, and the role of former political affiliations such as NSB membership. It challenges simplified Holocaust narratives, reminding us that experiences during the occupation often straddled ambiguous categories: “camp vs. free” and “victim vs. bystander” were not always clear-cut distinctions.

Aftermath

After 1943, Villa Bouchina ceased to function as an internment house. The building returned to Church property, with clergymen of the Christian Reformed Church residing there after the war — first until 1946, then another until 1952. Eventually, a new parsonage was built elsewhere, and the original villa was sold to a private individual. Over time, the memory of its wartime role faded, though scholars such as Chris van der Heijden have reconstructed its history and the stories of its inhabitants, preserving a largely forgotten aspect of wartime Dutch history.

Reflection: Why Villa Bouchina Matters

At first glance, Villa Bouchina might seem a minor footnote in the vast tragedy of the Holocaust. Yet it represents something far more complex: persecution could operate not only through brute force but also through bureaucratic manipulation, false promises of mercy, and strategies designed to coerce compliance.

Residents of the villa experienced a peculiar liminality: neither in hiding nor fully free, placed in a provisional — and ultimately lethal — purgatory. Their experiences remind us that survival under genocidal regimes often depended on arbitrary labels, social standing, and the shifting whims of oppressors.

Villa Bouchina challenges simplified Holocaust narratives and prompts difficult questions: Who counts as a “privileged victim”? How were false promises of safety used as coercion? And how do we remember those whose experiences defy neat categories of victim, collaborator, or bystander?

sources

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_Bouchina

https://www.tracesofwar.com/sights/363/Villa-Bouchina.htm

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment