I came across Gershon Willinger’s name on the Joods Monument website. It is his 80 birthday today, When I saw his name and his birthday, I also saw that the date and the place of his death were not known. I figured this was going to be an awful tragic and depressing story.

I decided just to do a bit of research, but with the thought, I wasn’t going to do a piece about him. I reckoned it was going to break my heart, and I just wasn’t able for that today. However, although his story is sad in many ways, there was another story emerging too, the story of Gershon. The reason why the place and date of death were unknown is because he is still alive.

This is his story in his words.

“My name is Gershon Israel Willinger. Born Gert Israel Willinger, Israel was given by the Nazi regime who was in Holland at the time so that became automatically my middle name or somebody’s last name, but it was my middle name, which is still carried today. I was born in September 1942 in Amsterdam Holland, where I grew up.

So I’m the man of many names, Gert Israel. I was born and until the age of 18, I was called Fritz. My last name was called Klufter because this was the name of my foster parents/ adoptive parents a year before I left. I didn’t want to be adopted, but it got me quicker out of Holland as well, because I got a Dutch passport. Born Gert Israel Willinger became Klufter. And then I had my Bar Mitzvah Gert Gershon, Gershon is a stranger in foreign lands, he was also the son of Moses. So very apt names for me. I still was called Fritz and the day on my 18th birthday, when I left Holland, I became Gershon.

I grew up in Holland, and I left Holland at 18 to immigrate to Israel. I went to the kibbutz. I then went into the army in 1961. I served two and a half years as a paratrooper in the Israeli defence forces.

Uh, then I studied social work. I became a social worker working with only youth juvenile delinquents and street corner groups. I was in the reserve for about 10 years, uh, fought during the war of attrition in 69, and 70 at the Suez Canal. I was with the entering to Jerusalem in 1967. I was not in the 73 war because I was studying for a bachelor’s degree and a graduate degree in the United States, uh, with my family. I came back during the 1973 Yom Kippur war, but, the trouble was that I couldn’t find my regiment. So I came with my whole family in the middle of my studies. We had to blackout our apartment and stayed for a number of weeks. And then when I couldn’t find them and things were, things were chaos. I stepped back on the plane and continued my education for the year in the United States with a wife and two small children in tow. And, um, we left Israel in 1984, uh, simply because of economic reasons for social workers is very hard also to not rely on family, but on yourself.

We have been here in Canada, which is quite a good country since December of 1977 and have lived here since raised our children here, our three children who are now 50, 48 and 45 and, seven lovely grandchildren between the ages of 17 and 11. I speak for the Holocaust Center of Toronto and for the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

I have a responsibility to my parents and I have a responsibility to my children and, uh, the Holocaust, I have a responsibility and it is, and, um, it’s not all altruism. There’s also an element of self-therapy, which is very good as well. Um, I’m one of the youngest. So from that point of view, I had to research my life most of my life, where I come from, and who you are. Because of the lack of identity of who you are as a person and many children who were born between 1935 and 1944, although there’s a vast difference because if you’re a child who grows up with a parent and a child who has got a history of family before the war, I’m still can relate to that. But then the other children who really after the second world war, which they don’t realize like me, and only some chaos, I suppose, in the background of your mind, but without any knowledge, you start starting after the war, which meant, uh, who are you? Where are you? Where are you going to be placed? What are you going to do? And what is your legacy, whether you, who were your parents how did they die, what happened and then so on?

My father was in the hospitality industry before the war. And he was Bad Wildungen and I felt first that he was born there, but he wasn’t born there. He worked there, he worked, it was a spa city with natural spas, with special water. He worked there in a Jewish hotel. He was a chef. He lived on the premises, it’s very picturesque between little hills. It’s like the gingerbread houses and beautiful, absolutely gorgeous. I’ve just, there’s nobody of us anymore in Holland because we were born there. We, my sister was there until 11 and left and at 18, I left and my parents came from Germany. Both of them are there. My mother came in 29. She came actually, she had relatives in Holland. I think that she went to my aunt, who I stayed with on 29. And she stayed in Holland, but she never naturalized.

My father, I found out was married to a non-Jewish Jewish woman in 1935. He divorced at 35. There became a law also that Aryans were not allowed to be married to Jews that became a law. But I think the marriage couldn’t have been that great either, but they divorced. And a, he came to Holland in 1937, 37 or 38 married my mother 37 I think it was. But, he still went back and forth to Bad Wildungen because there was a train from Amsterdam to there between 1935 and 1937. He travelled up and down and still stayed at the hotel and worked there. And finally, when people thought that he was a spy and I found it in the archives, because why do you go back and forth to Holland, the Nazi regime was already there? He stayed away and stayed in Holland, also not naturalized. So they got together, got married and then had my sister in May 1940.

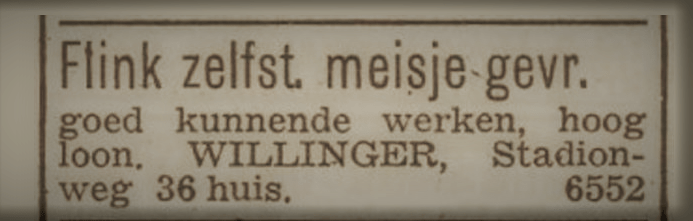

Now what possessed a couple, unless they didn’t have birth control to want another child in 1942? So they had me, you know, they must’ve thought that children could stay with parents or whatever happened. When they saw that things were bad, they allowed me at a very early age to be taken by the underground who knew about this baby. And my sister was already shoved underground somewhere else. And I came to this family, the righteous among the nations. The stories that my mother, my birth mother, Edith came to where I stayed and worked as a short-term maid at the farm across the brook so that she could have contact, not with me, but find out about me. But she went back to Amsterdam and they went for one day to Westerbork the transit camp. And I think it was the 29th of June that they came to Westerbork and then they were sent straight through to Sobibor where in July and the data I have is the 2nd of July, they were together murdered upon arrival in Sobibor, in Poland.

I was eight years old when I came to permanent foster parents. So what I do know is the time of 1945, 1950, when you are in as many children, displaced children also today in all kinds of countries, uh, you were going from pillar to post. So institutions are fringes, foster homes and not knowing even if you’re a Jewish. So the concept of being Jewish sounds very abstract. When you’re a small child, you don’t realize that at all. So, consequently, I was very, very, uh, curious to find out who I really was. And so from an early age, my new foster parents, after those five years have a bookcase full of authentic photographs from the Nazi time, also that they obtained with the bodies in this concentration camps and how the Americans found the camps afterwards.

So I used to leaf through them, and that is a psychologically, a very normal thing because the child looks for his parent. And so things that, the image of the parent. So, interests start already at that age. And, um, of course, you have a disassociation with people because you have moved around so much. So I, um, very quickly wanted to develop in the beginning of superficial sense of belonging to the foster parents that you live with in order to belong and to be somewhere, however, it never succeeded that much. Like many other kids, um, who were privileged, uh, like I was privileged to psychiatric treatment and psychoanalysis after the war for about five years when I came to them from eight to 13, then again from 15 to 17.

So I didn’t know what parents really meant. So, um, they told me that I did have parents, which I didn’t bemoan my fate because it’s very, normally if you don’t even remember parents that you had them, and I remember very hard to call them mom and dad, because, uh, you know, you get there at eight years of age, a very difficult child with lots of problems. And, um, but with a hunger for reading. So to save me because I was read, like a fiend. So, um, and I could read, well, uh, like many other children, my friends also that I have, who are my age, little bit older, little bit younger who, uh, belong to my group. I don’t know if you’ve heard that group of, um, I belong to a group of 50 children who in 1944 were sent from Westerbork in Holland to Bergen Belsen. We were there for a couple of months and then from Bergen-Belsen, we were transported to Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic. We were known as a Gruppe “unbekannte Kinder,” unknown children.

And what I tell usually schools is in order so that they can grasp especially grade seven and eights really like to talk to me because I ask them who tucks you in at night, who’s responsible for your food, who’s responsible for your clothing who’s responsible to take care of you and who loves you unconditionally, well it’s your parents. So now then put yourself in the picture of this and that happening.

I had their name, but never officially. My first name was also different because children went under, we had many names we had to deal with and cope with a lot of chaos and names. So my name was Fritz. Fritz was given to me by the people, the Schonewilles, who I lived with in Northern Holland, in the province called Trenta, who were righteous among the nations. And they took me in and they took care of me. But when my name was given away at the beginning of 1943, the very beginning of 1943, I was taken away by the Dutch police. Plenty many, many, many, many collaborators with the regime. The regime in Holland. Holland has got this wonderful connotation, wooden shoes, gabled rooftops, and it’s all very nice and pretty, but about 80% are either bad or are good people who did nothing. And about 15 to 20% put themselves out. And were treated abominably after the war, and didn’t get any recognition, only years, years, and years later. So those are the kinds of people that I was placed with. I was taken away from them and they put themselves really in danger because my foster father went to jail. I was taken away by the Dutch place and placed in Westerbork the transit camp.

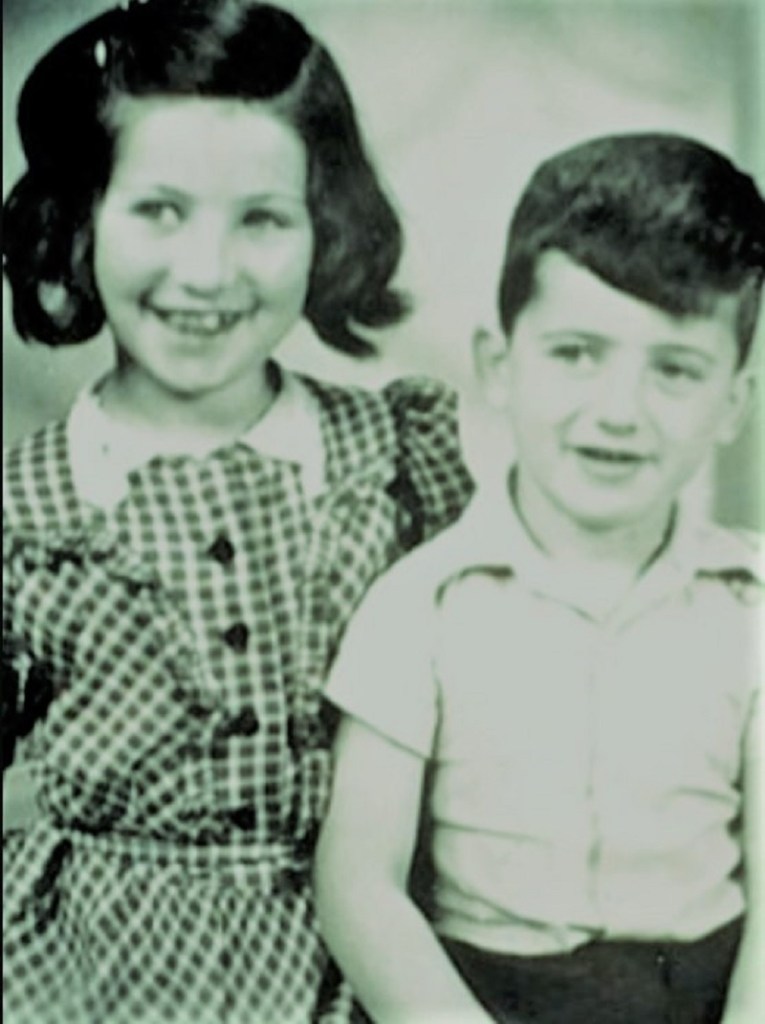

We knew it about each other. We never spoke about it. We were getting ready to go to Israel, we were Zionists and even not going to stay in Europe. And I stuck to that. I never went back. I never stayed in Europe. And I left Israel. I said, leave Israel, but not back to Holland or to Germany because actually I’m, uh, I’m Dutch because I was born there and I was raised there. My sister was there until she was 11 years old. My sister’s name is Rita. She was born in May of 1940.

You have no nationality and again, no identity. So the memory of that is not that great. I lived with my foster parents and we went to Belgium, France, and Italy because they were quite well-to-do Dutch Jews. Um, I had to also have special dispensation from the courts and I had a different, I remember a passport was pink instead of blue or a solid colour … I was on refugee status, although I was born in the country. And there was no adoption. So finally, when I was 17, my foster parents adopted me to give me a name and give me citizenship.

I am Jewish by religion, by birth first by birth, by religion and by tradition. And by way of life, I would actually put religion and the, and the traditional out of, out of context here and talk about I’m a Jew by birth and way of life. It’s culture, it’s everything. It encompasses everything for me. It’s just, that’s how I live. It is to me, it’s, it’s a way of life and the way of life is in the mind as well. It’s a way of life. It’s very hard to interpret it a little bit is religion, a little bit of this, a little bit as that in your general behaviour, uh, your reactions. If you’re not exposed to Judaism at all, there may be a spark somewhere that still has to be developed. It isn’t developed yet, but I do believe there is some, um, you can be a Jew by choice and be really Jewish if you do buy. But if it’s from birth on and off, or even a little bit later, it’s a way of life and a tradition that you accept with all its positives and negatives.

I think I have a duty as a Jew to tell my story to the world because every story of every Holocaust survivor is unique because they’re different people and different within themselves. Perception. You need to listen to as many stories. And I, a Jew am a normal person like any other person, the soul, two legs, wants to make it in life. We have certain attributes. We live our religion a bit differently, like everybody else does as well. In a fight against bigotry, hatred of Jews is the oldest hatred that exists. And that’s why I find it very important because we need to always have hope. It’s not my little story that I’m going to tell you here is not going to change people, and their attitudes, but I want to have an understanding that they can choose what they think. That’s very important for me that people understand what the Holocaust is about. Another reason that I do it, I owe it to my dead parents so that they’re not just ash. So that they, and they don’t have a proper grave. So they don’t just become a number. So during my lifetime I at least bring them to life through photos, through pictures. There, there is a story attached to me in my background, people who were murdered because they were good people and didn’t do anything. And it’s also very good. And it’s good for my own psyche to talk about it because it gives me a sense of belonging. It gives me a sense of self and validation that I exist.

What happened is somebody in Germany he contacted the Holocaust Center of Toronto, a number of years ago. And says we have this name, we have got this, this, I don’t know how he knew I was in Toronto that I was here. He found out and he contacted the Holocaust Center, said there in Bad Wildungen, where my father worked, there was a Stolpersteine, five Stolpersteine up, uh, at, at a little Stiebel which was once a synagogue. But below there, because didn’t know exactly know where those people lived. And my father lived in the hotel. So what Jane and I did was we made a special trip to Germany for the first time, because I never had a gravestone of my parents. And it was only the gravestone of my father you know, the Stolperstein you know, how they look and what they are.

And I remember we saw it and, uh, we went to see that, and these men took us there. The Bürgermeister, the mayor of the town came, he brought a little thing and we polished the stone and it was of five other people. And I didn’t cry. It was not even emotional because I, I think, cried enough all my life. And had been through all the emotions of first being labelled as not a survivor, and being asked by other Holocaust survivors, you call yourself. So, you know, the survivor, you don’t know anything. You don’t remember anything, another slap in the face, you don’t belong anywhere. So anyway, that gives you somewhere to belong. And I cleaned it up very nicely. We stayed a week. We went to the place where my father worked, which doesn’t exist anymore, but it became a spa for people who are sick with asthma breathing. What is unique about it is that it is for me personally unique, it’s the only gravestone I have of my parents. It’s really ridiculous even to think about it, that only, the only gravestone is in Germany, but it’s there. And, uh, that I felt so at home, in Germany with the Stolperstein maybe it’s my culture where I come from. And I say, Hey, I don’t like nasty people, but these people are good people. And, um, I felt this is something that I can touch, it tangible it’s something of my parents. And it was very important to me. And it was a gravestone to me. It was great, but, also that the place that you walked, that you did, you walk over, it doesn’t bother me at all, because if it would be on the wall, I would have to turn my head.

What I also felt was that if it is on the ground, they have to put themselves out for half a second, too. I’m certainly not insulted, some people have got this mishagas you walk on. I have no problem. If you walk over it, it means many people go past it because, uh, it will be more polished. The second time I went, I said, you know, something that he said, the stone of your father is going to be taken away from here and placed now where he worked and lived on the main street. I said, that’s wonderful. I said, now I have a request. My parents were murdered on the same day in the same concentration camp. My mother is originally from Germany. Although she is not from this town because Stolpersteine is more of a, you worked or where you lived. I pay for it. Please put my parents, they were married, put them together as a Stolpersteine. They say, not only will we do it, but it’s not your business to pay for it, we should. So I went again, said Kaddish again with all my Christian Germans around me and for me, and that’s what the Stolperstein does for me. It gives me a historical feeling that I belong and that people still care. Whether it’s out of guilt or not, I don’t care. It’s still it’s there. And my parents were Germans. They were transplanted to Holland out of necessity, but they have still were entrenched in the German culture, and German society when they lived there, especially the ones that lived in small towns.

Reclaiming in a sense that that’s, it’s part of me, it’s part of my history. It’s part of who I represent and it is fine. And I don’t need to make excuses if people don’t like me because of it what can I do? People understand people do understand, uh, especially Holocaust survivors who I speak with, they understand, uh, especially now that I have a Stolperstein there it’s a Stolpersteine is the, it’s the plural. Yeah. There’s an attachment. It had an impact on me as I … it’s very hard, but you try to visualize that he actually walked there and he lived there in that. And it’s the town. Yes, it had spread out, it is modernized a little bit, but it’s still the core. The old city is, it’s all still the same. And, and, and so you like to, you like to transport you back in the past yourself, back in the past and your hunger actually to know and experience, but you can’t experience because you’re in a different day and time, but what he experienced through would have liked to experience.

Yes. And that is the feeling that I had. So yes, it had an impact, but not in a sentimental way. Uh, just, uh, Hey, this is me, this is again, part of the puzzle that needs another little piece of the puzzle that goes in that I. And there are still pieces of puzzles that I, uh, I’m looking for in my mind, uh, uh, about family, about the security that the history really is the history as it is about myself because many children who live today who are wartorn deal with search. They search and always need to develop themselves and be proud of themselves because their identity is so weak because of the displacement and because of where they have had to go and how their life went. So I’m very, always very interested today in the downtrodden really.

You always were in search of who am I. What am I? So there’s the big difference that the horrors of the concentration camp, you don’t remember, you don’t know anything about, but you also don’t have the memory of who are you as a family. It could equate to kids from Syria and from wartorn areas from the Rohingyas and Yazidi and people get murdered left right and centre today. And so it’s really a very similar story only that this was very planned because you have to really define what is genocide and what is Holocaust. There are very different things the Holocaust is a planned annihilation of a people over a long period of time. Not necessarily in one geographical area, which happens. Genocide is usually a spontaneous annihilation of people, bad.

Everything is bad, often in one geographical area and a shorter period of time, not planned necessarily spontaneous, more spontaneous annihilation. So that’s that’s really the difference with the Holocaust. The difference is also, of course, that we spoke different languages. We adhered to different laws. We were members of different societies in different countries, which we were involved with in government and in arts and army in whatever way we were involved with. So, so it’s, it’s unique. Yeah, it’s unique because what do we have to do in 2021 (almost), with the Holocaust of all those years ago? You have to make it also so that it can be understood by children. And as long as we are alive still, it’s our duty to speak. Well, life is very different, but, but what parallel can I draw? Children are children. They’re spontaneous, they ask questions and there are no inhibitions.

And, they ask if some misconceptions, and they know what parents tell the right thing or not the right thing, but they are inquisitive. They want to know, but it’s how you transcribe your knowledge, how you—how you get—how you put it in front of the children. Um, children are children. They are the hope of the whole, the future. So the more, if a child is indoctrinated to hate somebody at a very early age it’s very hard to get it out of the child’s system. If a child gets indoctrinated at a very early age with goodness and equality, it’s very hard to get out of their system. So that’s what we have to do. So that’s where I see the parallel. It’s all up to the adults to guide the children. And then I see a parallel that children can be. Uh, I see also little children, teenagers in Nazi Germany can be also because of society be, um, although there are many Germans who knew the difference between right and wrong. But if you are allowed to go to a sports school and you go to the mountains to have a nice vacation and you belong to the Hitler Youth, you’re damn sure you’re going to belong to the Hitler Youth otherwise, you’ll get ostracized and you have no good. You haven’t had a good time. So you do that.

So it’s really up to the children to learn, and I, and I think nothing has changed. The child should know the difference between right and wrong and what it means to be a bully, what it means to be all-inclusive, but the child has to have it in them as well. But it has to also, uh, it has to be nurtured by parents, by educators and if you got the stuff nurtured the proper way. And then, then, uh, it’s usually the fright with children also of not knowing of what is strange like with adults., oh no we get to know each other suddenly, and yeah, it’s actually quite nice to find out that you have a different, different traditions, different way of life than I have.”

I met my wife, Jane (née Levy), in England, and we were married in Israel in January 1970. We have three children and, to date, seven grandchildren. In December 1977, we immigrated to Canada. For the first number of years, I was employed as a youth and camp director for the Hamilton Jewish community. In 1984, I joined the Children’s Aid Society as a social worker, specializing in working with abused and neglected children. I retired in 2003.

I am active in the Jewish community and spend much time lecturing about my past experiences. In June 2006, we moved to Thornhill to be closer to our children and grandchildren.”

Dear Mr. Willinger, I wish you a happy 80th birthday and I hope your story will be an inspiration for many.

Sources

https://stumblingstones.ca/gershon-willinger

https://memoirs.azrielifoundation.org/exhibits/sustaining-memories/gershon-willinger/

Leave a comment