This is a long read, but it offers a compelling glimpse into daily life in the Netherlands during World War II. Despite the horrors, life continued—though not for everyone. Tragically, 75% of Dutch Jews were murdered during the Holocaust. Some of them had worked in the luxurious department store Bijenkorf and its affiliated store HEMA. Meanwhile, other Dutch citizens had to learn how to cope with the harsh realities of the ‘new normal’ under occupation.

De Bijenkorf, one of the Netherlands’ most iconic department stores, has a long and complex history that intersects with the tragic events of World War II and the Holocaust. Founded in 1870 in Amsterdam by Simon Philip Goudsmit, a Jewish entrepreneur, De Bijenkorf grew from a small haberdashery into a luxurious department store known for its elegant merchandise and modern retail approach. By the 1920s and 1930s, it had become a symbol of sophistication and urban modernity in Dutch society.

However, with the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, the Jewish ownership of De Bijenkorf put it in grave jeopardy. The Nazi regime implemented a process called “Aryanization,” which involved systematically stripping Jewish individuals and families of their businesses, wealth, and civil rights. The Goudsmit family, like many other Jewish business owners, were forced out of the management and ownership of the store.

During the war, De Bijenkorf was placed under non-Jewish management, and the original Jewish owners were effectively erased from the company’s public identity. The store continued to operate, albeit under Nazi oversight, and like many institutions in occupied Europe, it was caught in the difficult moral terrain of continuing business while its rightful owners faced persecution.

Members of the Goudsmit family were personally affected by the Holocaust. Several were deported and perished in concentration camps, including Auschwitz. Their suffering reflects the broader destruction of Jewish life and culture in the Netherlands, where approximately 75% of the Jewish population was murdered during the Holocaust.

After the war, De Bijenkorf continued to exist and eventually thrived again in the postwar era. However, the story of its Jewish founders was largely forgotten until later historical investigations brought it to light. In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the store’s Jewish roots and the injustices its founders faced, prompting public discussions and acts of remembrance.

De Bijenkorf’s history during World War II is a reminder of how deeply the Holocaust affected all facets of life, from personal tragedies to the reshaping of business and culture. Acknowledging this past is essential in honoring the victims and understanding the broader consequences of systemic persecution.

At the end of the 1930s, De Bijenkorf was still entirely in Jewish hands. For although the influx of external capital had significantly increased, Arthur Isaac, Alfred Goudsmit, and the German investors were able to maintain control over the company thanks to an oligarchic structure. The founders held so-called priority shares, from which they derived important powers—such as the right to nominate new members to the Board of Management. As a result, both the Board of Management and the executive board during those years were composed exclusively of Dutch and German Jews. Representing the German investors, Leo Meyer had been part of the executive board since 1914. The trio of Meyer, Isaac, and Goudsmit formed a strong and strategically adept management team.

The management layer below that level—both in the branches and at HEMA—also consisted entirely of Jewish executives, including the three sons of Arthur Isaac: Hans, Hugo, and Frits Isaac. In those years of rapidly growing antisemitism, it was therefore not surprising that De Bijenkorf frequently became the target of attacks by the NSB and other fascist groups, who publicly declared that De Bijenkorf was run by ‘alien elements.’

Frits Isaac, Arthur’s eldest son, had reportedly considered emigrating to Palestine with his family in 1939, according to his son Arthur. However, a strong sense of duty and deep attachment to De Bijenkorf ultimately prevented him from doing so.

In the May 1940 issue of the staff magazine Bij en Korf, there was little indication of the tragic events that would soon shake the country to its foundations. Since September 1939, attention had regularly been paid to mobilized employees, and in April 1940, it was noted that ‘Some members who did not possess Dutch nationality had resigned,’ referring to four German-Jewish members of the Board of Management. Beyond that, however, the first wartime edition of Bij en Korf reflected the normal day-to-day operations of the department store.

Yet even by that time, significant changes had already taken place at the top, such as the departure of Director-General Leo Meyer to the United States in September 1939. Leo Meyer had been fully aware of the threat posed by National Socialism hanging over the Netherlands and, following the German invasion of Poland, had decided to bring forward his already planned departure. After having been an active part of the management for 25 years, the farewell was a difficult one; Alfred Goudsmit praised his tireless work ethic as a major contribution to the company.

In November 1939, all German-Jewish members of the Board of Management made their positions available for resignation. ‘Given the current circumstances, it seems to me and my fellow members of non-Dutch nationality to be in the best interest of your company that it be based purely on a Dutch foundation,’ wrote one of them to the management. (Letter from A. Schöndorff, November 10, 1939)

n May 1940, Alfred Goudsmit fled with his family by boat from IJmuiden to England. One day before his departure, he wrote an entry in his diary

“DIARY MAY 1940

Memory of the last evening before the war began in the Netherlands.

Thursday, May 9 in Blaricum.

Mrs. Van Tijn came for dinner. Took her home around 10 p.m. and walked back. Beautiful evening and starry sky. On the way, talked about the possibility of war in the Netherlands.

Early morning, around 4 a.m., Martien is at the door of our bedroom and we wake up. Roaring of airplanes overhead. What is going on? A drill with our own aircraft? Or something else? Then come the reports from the air force service of aircraft of all types flying over in a northwesterly direction. Could it be an attack on England? But then come reports of bombings and parachute landings, and we know what it is: “the war.”

I go by bicycle to the village where everyone is in the street, but no one knows more than we do. Back home again, discussing what I should do to get to Amsterdam. Car is too risky, so I take the bicycle, some sandwiches in my pocket and dressed warmly after a hasty breakfast. Depart at 5:30, arrive in Amsterdam at 7:30. Lots of cars on the road in both directions. Also many people around Brediusweg. In Amsterdam, things are chaotic. Around ‘De Korf’ (Bijenkorf) people are talking and not working. At 8:30 a.m., meeting. Brief words spoken to the staff. Phone call with The Hague and Rotterdam – within 4 days, contact is no longer possible. Store opens at 9 a.m. Meeting with functional managers. In the store, everyone is very concerned but calm. No one sits in the office.

At 11 a.m., Board of Management meeting, called at my request. Hochheimer summoned.

It’s decided to pay staff half a month’s salary for Sunday. All Germans receive notice and must remain in their homes.

The store is quiet, but in fact, there’s nothing more to be done.

Air raid protection articles distributed. Slept at Hans’s.

Saturday: Situation barely changed. Around 11 a.m., first bomb attack. Everything in the shelters. Attempt to obtain a “laissez-passer” for Sunday to get from Blaricum to here. Fred Polak tried various contacts, including Prof. Revesz. Pass eventually granted. At 12:30 p.m., with a chauffeur and car from Hema to the area commander at Stelling with introduction from Prof. R. Around 6 p.m., arrived in Blaricum where children welcomed us with cheers.

5 evacuees taken in from Baarn. Entire Laren and Blaricum filled with residents from Baarn. After dinner, went looking for Mayor Klarenbeek. Appointment with Gertie and Renee to bring to the Berg Foundation and then take in 2 people, which happened. Miems and I also at 10 p.m. to the village to bring 2 elderly people from the Protestant Church to our home. Church filled with refugees. Had 8 days before celebrated golden wedding. The church full of refugees.”

On Tuesday, May 14, 1940, Heinz Littaur, director of the Rotterdam branch of De Bijenkorf, celebrated his fortieth birthday.

It would hardly be a festive day, as the Netherlands had already been at war for four days. The modern Rotterdam Bijenkorf building had a well-equipped air-raid shelter, where dozens of people sought refuge during every air-raid alarm—including soldiers who could no longer be admitted to the hospital on the Coolsingel.

That morning, in the shelter, Heinz Littaur gave an encouraging speech on the occasion of his birthday. The situation was certainly difficult, he said, “but tomorrow, De Bijenkorf will open again as usual.”

Things would turn out differently.

Around midday (by then, Littaur was at home with his wife and children), the historic city center of Rotterdam was destroyed by German bombers. The attack resulted in many hundreds of fatalities and thousands of injuries. Another 80,000 people were left homeless in an instant. De Bijenkorf was also hit—twelve bombs caused complete devastation. Miraculously, the air-raid shelter remained intact. Only one staff member, Mien Goppel-van Klaveren, lost her life, but she had been outside the store during the bombing.

The ten-year-old creation of the famous architect Dudok was two-thirds destroyed, and it took more than a week to extinguish all the fires.

In a moving editorial in the June/July 1940 issue of Bij en Korf, Frits Isaac commemorated the first war casualties among the Bijenkorf staff. He also announced a decision meant to alleviate the worst suffering of the 149 affected Rotterdam employees:

‘…that the management has decided to provide completely free of charge the most essential items for furnishing a new home to employees and their families who have lost all their belongings…’

It would take until January 22, 1941, for the damaged section of the Bijenkorf to be repaired enough to reopen. The renovated portion covered approximately 7,000 m² of retail space—still relatively large compared to the 9,600 m² of the Bijenkorf in The Hague.

This Bijenkorf, quite literally risen from the ashes, would remain in service until 1957.

The ‘Voluntary’ Aryanization

According to Professor Weijer, the new member of the Board of Management, the overrepresentation of Jews in the executive board and the Board of Management posed a problem—or at least, it could become a problem if the occupiers were to implement anti-Jewish legislation in the Netherlands. After all, it was to be expected that, as in Germany and Austria, the business sector here would also be subjected to Aryanization, which by June 1940 had not yet occurred.

However, in August 1940, a German accountant, acting on behalf of the occupiers, conducted an investigation into “enemy” capital—also at De Bijenkorf. While it turned out that there was not a significant amount of enemy capital involved, the accountant did find that Jewish influence within the company was disproportionately large. As a result, he advised that the composition of both the Board of Management and the executive committee be entirely Aryanized, and that the priority shares be transferred to a new, Aryan company.

Encouraged by this advice, Weijer and Grosheide took the lead in implementing the voluntary Aryanization.

Not only were all Jewish members of the Board of Management and executive board forced to step aside in favor of non-Jews, but Jewish senior staff at both De Bijenkorf and HEMA were also replaced.

In practice, the Jewish executives remained active in the background as advisors. However, this “voluntary Aryanization” ultimately proved insufficient: in March 1941, a formal decree was issued for the removal of Jews from economic life. The Germans were now granted the right to appoint a Verwalter, an administrator who would assume control of the company.

Discontent among the Jewish population was growing. Clashes increasingly broke out between the W.A. (Weerbaarheidsafdeling)—the paramilitary wing of the Dutch National Socialist Movement (NSB)—and groups of rebellious Jewish youths.

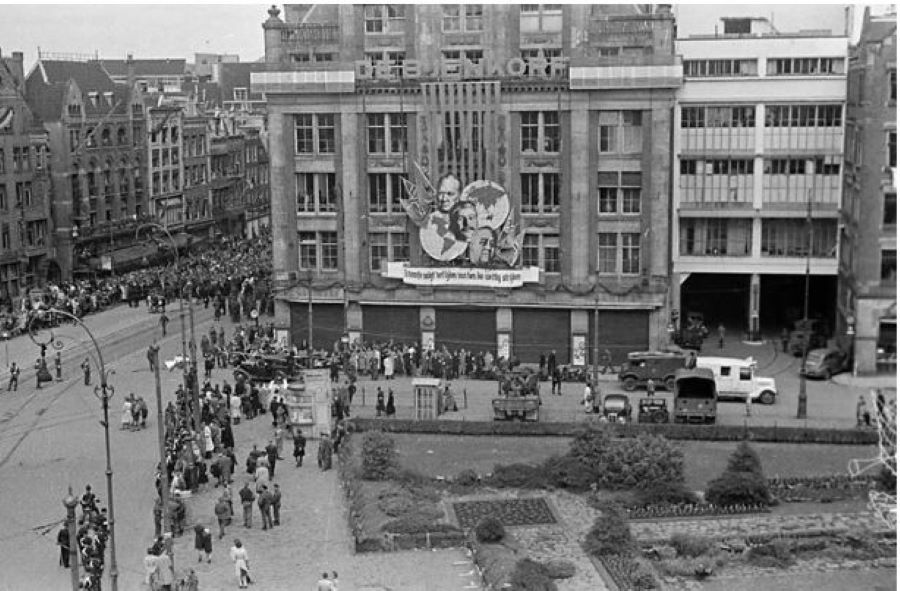

On Sunday morning, February 23, 1941, German forces arrested hundreds of young Jewish men in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. They were ultimately deported to concentration camps. These large-scale raids (razzias) led two days later to a massive protest action that would go down in history as the February Strike.

On Tuesday morning, February 25, trams remained in the depots. The general strike against the first German pogrom had begun—and De Bijenkorf in Amsterdam took part. In the tunnel beneath the central light court (known as the Beursstraatje), fighting broke out. A German soldier threw a hand grenade, injuring Bijenkorf employee Alie Langeveld.

After management observed that a large number of departments had already been completely abandoned by their staff, an announcement was made via the store’s PA system at 11:40 a.m.: due to lack of personnel, the store would close at 12 noon. At the same time, however, employees were urgently requested to return the next morning at the usual time.

The following day—by which time male Jewish employees had been quietly given the chance to leave if they wished—the staff again gathered at opening time. Some employees were willing to return to work; others remained outside. Fearing German reprisals if the store remained closed again, the directors also went outside and urged the assembled staff to return to work.

“Suddenly, ten raid vans full of SS men showed up,” according to the eyewitness account of one employee. “They drove onto the Beursplein toward the staff entrance. Suddenly I saw an object flying through the air, and immediately there was a massive explosion, and all the windows shattered. Then the police started beating people with drawn sabers, and everyone scattered.”

By the end of the day, four men from the Grüne Polizei arrived to arrest directors Wolsheimer and Hans Isaac.

Wolsheimer was quickly released, but Hans Isaac was held at the Lloyd Hotel, from which he was released a week later thanks to the intervention of Gé van der Wal.

The next day, fears of reprisals proved to be justified: on February 27, 1941, Generalkommissar Fischböck placed the company under official German administration (Verwaltung).

Under Verwaltung

The occupiers did not act half-heartedly: the entire Board of Management was replaced by a German Verwalter, Dr. Paul Brandt. Two collaborators were added to the executive leadership: Gieskes and Graafstal.

Gieskes had previously been a hat buyer at De Bijenkorf before opening his own store across the street. Graafstal had initially worked in the company as a buyer for the handicrafts department before becoming an independent manufacturer. Within the NSB (Dutch National Socialist Movement), he had risen to the position of district leader in Utrecht.

The most dramatic change occurred when, as a result of German measures, one-third of De Bijenkorf’s 3,000 employees were forced to leave.

Exemptions could only be requested for “indispensable” employees and those in mixed marriages—although the latter still had to wear the Star of David.

All Jewish employees were without exception replaced by NSB members.

What happened to the Isaac family?

Hans and Hugo went into hiding in Belgium, while Frits, with the help of the Parool resistance group, managed to escape to Switzerland with his family in November 1942, after an arduous journey of three weeks.

Huge gaps were left in the organization, which proved difficult to fill.

By then, there was little left to sell: three of the four floors of the Amsterdam store were half closed, and opening hours were restricted.

Employees were required to attend German propaganda afternoons held at Hotel Krasnapolsky.

Gradually, more and more products were added to the ration list.

In the August/September 1940 issue of Bij en Korf, readers were given advice on how to wisely spend their hundred textile ration points—as textiles had been rationed immediately after the capitulation.

Still freely available were silk stockings, velvet fabrics, hats, and furs.

Although there was understandably little new in the field of fashion, a range of practical, time-specific products suddenly appeared—for example, gas burners that could be mounted under a kerosene stove.

There were also reports of a “cigarette shortage”, and the grand comeback of the monkey coachman (a popular mechanical toy or decorative item of the time).

De Bijenkorf began selling Sanka Tropid, a type of coffee substitute, which allowed people to get four times more out of their coffee ration coupons.

Other innovative wartime products for saving resources included:

a paper briquette press

a dust-free ash sieve

and candles that could burn for 250 hours

Armed with these tools, people entered the first dark winter of the war.

1941: Bare and Cold

The New Year’s greeting of 1941 was signed by the new directors Wolsheimer and Van der Wal. “Nevertheless, the times continue to weigh heavily on us,” they wrote, among other things, and they called on people to “…banish darkness and fear of the future from their minds…” Their words conveyed, as would later prove misplaced, a confidence that the occupation would not be too harsh.

The new items mentioned in the staff magazine were mainly aimed at “alleviating the many restrictions we must impose on ourselves.” For example, there was an electric energy-saving stove that consumed only half a cent per hour, and a new type of flashlight, with instructions to return depleted batteries when purchasing new ones to prevent shortages of raw materials. Other new products mainly focused on substitutes, such as pepper substitute and ‘head cheese’ made from mussels and fish—a tasty and boneless sandwich topping. The Bijenkorf also introduced two of its own brands of soap substitutes.

In April 1941, the hundredth issue of Bij en Korf appeared, which, unexpectedly, would be the last for the time being. The anniversary gave no cause for celebration, “because it is so insignificant amid what is happening, developing, evolving around us in the company, indeed within ourselves.”

To keep the store running, managers had to bend in sometimes impossible ways. The scarcity of goods became increasingly severe from 1941 onwards. Some customers became more critical because they could only use their ration coupons once. At the end of December 1941, the entire stock of woolen blankets in the Bijenkorf disappeared: confiscated by the Germans. To still be able to sell something later, a maximum purchase amount per day was introduced.

All in all, the atmosphere in the store naturally did not improve, partly because saleswomen sometimes tended to favor certain customers, such as friends and family. Purchasing also encountered increasing problems with suppliers when ordering the necessary assortments. It became bare and cold in the Bijenkorf—literally: due to the lack of fuel to heat the store, saleswomen kept their outdoor coats on inside.

Loss and Success

The increasing scarcity and the deliberate choices made by management regarding purchasing and sales became visible in the strongly fluctuating turnovers. Those of departments with many rationed goods already declined significantly in 1941 and 1942 due to the extremely limited transportation possibilities throughout the country. The textile departments, in particular, suffered heavily. The total turnover of all textile and fabric departments in the Amsterdam Bijenkorf was almost twenty percent lower in 1941 than in 1940, and in 1942 it had to be reduced by another ten percent.

And that while the prices of most articles had by then risen considerably. The turnover of the women’s coat department in Amsterdam in 1941 was more than halved compared to the previous year, and the same applied to various fabric and linen departments.

On the other hand, the so-called free departments (outside the rationing system) performed well and were successful. The policy to stimulate the sale of ration-free articles bore fruit. These departments were specially highlighted by giving them a more prominent place in the store.

A fine example was the department Elck wat Wils, opened in the fall of 1941 in all three branches, in a strategic location on the ground floor. Also new was the antiques department, which—like the departments for books, art, jewelry, office and writing supplies, toys, and furniture—achieved good results. The share of textiles in the total turnover of 1942 fell from fifty-five percent before the war to forty percent. The turnover of groceries also declined sharply. The shift toward hardware and Ersatz goods only partially compensated for the decline in textile sales.

Pricing Policy

De Bijenkorf consistently adhered to the guideline that regulations regarding sales prices had to be strictly followed. According to Hans Isaac, this policy was necessary because De Bijenkorf was more vulnerable in this area than many other specialty stores. Price control, according to the management, was a subject where old tensions between large and small retailers could easily flare up again. Violating pricing regulations could bring De Bijenkorf a great deal of negative publicity.

According to Hirschfeld’s pricing decrees, retailers were allowed to raise sales prices if the manufacturer had indicated the cost price increase on the invoice.

Nevertheless, in 1941, disciplinary proceedings were initiated against De Bijenkorf in Amsterdam because the inspector had found violations of the price control regulations. The management viewed this case as a matter of principle and defended itself—through Gerrit van der Wal, Frankenthal, and Mr. Verdam—against the findings in the report.

The report mentioned that only 0.2 percent of articles involved a violation, based on a total of 700,000 invoices, which the management argued was negligible. Van der Wal requested that the inspector impose a fine of five hundred guilders, so that they could appeal the case to a higher court. But the inspector dismissed the case, and that was the end of the matter.

Textile Shortage

In the second half of 1943, the shortage of goods in the textile departments became acute. This forced the distribution apparatus to intervene even more drastically. On June 12, 1943, Distex (the National Bureau for the Distribution of Textile Products) took full control of textile distribution, and from that point on, the industry was only allowed to supply retailers under the direction of Distex. On November 15, 1943, distribution was completely halted; from that moment on, textile products could only be obtained with a special permit.

Just before the total ban was implemented, stores made one last large purchase of textiles, which allowed for large-scale textile sales in October and November. De Bijenkorf also took part. According to Mr. Hoefsloot, who was temporarily replacing Heinz Littaur as director in Rotterdam at the time, “textiles were thrown around” during those two months.

By 9:45 in the morning, a massive line of eager customers had already formed in front of De Bijenkorf in Amsterdam. Partly as a result of this surge, De Bijenkorf achieved higher sales in 1943 than in 1942, although this could not prevent the textile share of total turnover from continuing to decline—reaching a dramatic low point in 1944.

The Sale of De Bijenkorf

In April 1942, Brandt stepped down as Verwalter (trustee). He was succeeded by the accountant Willy Minz, who came from the Niederländische Aktien Gesellschaft, an institution responsible for determining the value of Jewish-owned companies that were to be liquidated. Minz’s task was to set the price at which De Bijenkorf would be sold.

The process of bringing De Bijenkorf under German control was made easier by the existence of priority shares in the Bijko-Priora company. The Germans declared the transfer of those shares to Bijko-Priora by the original owners invalid. After the enactment of the “Regulation on the Treatment of Jewish Financial Assets” in August 1941, Jewish shareholders were forced to hand over their Bijenkorf shares to the German-controlled Lippmann-Rosenthal bank.

All the shares that had previously formed the working majority thus ended up at this bank, where they waited for a buyer. There was no shortage of interested parties. In addition to several Dutch candidates, the Dresdner Bank—which had previously shown interest in De Bijenkorf during the founding of Bijko-Priora—also reappeared.

Yet it would take another two years before De Bijenkorf was actually sold, a sign of the cautious and methodical approach taken by the Germans.

On October 19, 1943, the Wirtschaftsprüfstelle (Economic Audit Office) instructed Lippmann-Rosenthal to release the Bijenkorf shares. The share package was divided between two buyers: the Hamburg trading firm Riensch & Held, and the German businessman Fritz Kötter. Since they had acquired the majority of the priority shares, they were together able to take control of the company.

On November 29, 1943, the Verwalter convened a general shareholders’ meeting—the first since the company had been placed under German administration in 1941. Of the Dutch shareholders, only two were present, both journalists, each holding a single share. On the German side, in addition to Verwalter Minz, the new German shareholders were present—that is, Fritz Kötter and several representatives of the Köster Group.

Mr. Minz announced that the administration (Verwaltung) would be terminated as of December 1943, meaning that the regular corporate governance bodies could once again assume control of the company. A new Board of Management was appointed, staffed with several Germans. Two new general directors were also appointed, while Graafstal and Gieskens remained in their positions.

The position of Gerrit van der Wal, who was widely respected, was not discussed during this first meeting of the new board.

However, he was asked to remain in his role even after the company was taken over by the new shareholders. He refused, stating that his position as general director stemmed from his appointment by the original shareholders, and therefore he could not accept a position offered by the new board. His refusal was poorly received by the new owners, upon which Van der Wal resigned, thereby proving his loyalty to the original owners.

With his departure, De Bijenkorf lost its last senior executive who had remained since the February Strike.

Under German Administration

After the departure of Van der Wal, very little actually changed in the leadership of the company. However, Graafstal and Gieskens were required to report regularly to Emil Köster, who, for the most part, remained in Germany.

The new owners gained little from their purchase. They had acquired the company just as sales were beginning to decline sharply. As a result of the growing scarcity in occupied Netherlands, the company’s operations came under severe strain: stocks were depleted, and purchasing new goods was nearly impossible.

Despite German measures—including the forced departure of Jewish employees, the mandatory transfer of priority shares to foreign new owners, while the Isaac and Goudsmit families watched helplessly from their temporary homes in America, Switzerland, and Belgium—a spirit of resistance remained alive within De Bijenkorf. Stocks were hidden from view, and the Verwaltung’s policies were undermined in various ways.

Commercial inventiveness also remained intact. Advertisements and mailings encouraged customers to revamp their wardrobes with simple methods—to make dresses, pants, or jackets look like new again without needing ration coupons.

A brochure titled “It’s not as hard as it looks” offered thirty tips to inspire customers: how to turn an old men’s winter coat into a like-new women’s coat, or how to transform two worn-out dresses into one new one. In a shop window at the De Bijenkorf in The Hague, an example was displayed showing how two old bed sheets could be turned into a stylish, waterproof raincoat.

But no matter how creative the efforts were, supplies continued to dwindle, and more and more departments had to be downsized or closed.

Still, there were departments that suffered less. Reading provided comfort to many during these hard years, and the demand for books remained high. An added benefit was that books could be restocked more easily than other goods. Former book department manager Ammerlaan in Amsterdam recalled how his department was given extra storage space during the war, and he eagerly increased his orders to better serve his customers.

Economic Chaos

The nationwide railway strike in September 1944 can be seen as the beginning of the final phase of the occupation, a period marked by German terror and economic chaos. In the last nine months of 1944, the supply of goods to the western Netherlands collapsed entirely, as did the import of coal from Germany. Whatever textile stock remained was seized by the Germans through looting and requisitioning.

De Bijenkorf in Amsterdam also became a target of this criminal strategy. In October 1944, Obersturmbannführer Prüfert visited the store. In the absence of Graafstal and Gieskens, he was received by branch manager Nanno Hendrik Benninga. Prüfert wanted to confiscate all remaining matches in stock. When Benninga asked if a portion could be left for customers, Prüfert responded by striking him hard across the face and taking the entire stock.

De Bijenkorf faced problems on many fronts: due to a shortage of coal, the heating had to be turned off. The electricity supply was so poor that the elevators stopped functioning, and goods had to be hauled up to the higher floors using a simple pulley system. Yet the store remained open. During the harsh Hunger Winter of 1944, Benninga emerged as a kind of father figure, doing everything he could to keep up the staff’s morale—both through his strong personal commitment and by organizing material support. He ensured that employees had priority access to scarce goods at reduced prices. He also remained in contact with Gerrit van der Wal.

In December 1982, former employee Lien Tabakspinder recalled in an interview with HP:

“I worked in accounting, alongside NSB members, and you just didn’t get involved. And the strange thing is: one moment a Jewish colleague was there, and the next—gone. Later, I couldn’t understand how easily we accepted that at the time. When I wanted to leave, they didn’t accept my resignation—they just transferred me to purchasing. There I forged invoices, because goods were being purchased without the knowledge of Graafstal and Gieskens. I never set foot in their offices. In the evenings, I delivered mail to Gerrit van der Wal’s house, in the dark. I was at De Bijenkorf more often when it was closed than during the day. We were trying to save goods, of course. I packed them in the basement under carbide light, and we took them to Maarten Toonder on the Prinsengracht, where we were allowed to store the suitcases in the cellar. We had a tiny group—just six of us.”

The leader of that group was Benninga, who, after Van der Wal’s departure, was the highest-ranking “good” Dutchman remaining on the Damrak. Thanks to people like Lien Tabakspinder, an underground support network was built that provided employees with potatoes, firewood, toothpaste, and other hard-to-get essentials.

To do so, Lien collaborated with a railway official in Amsterdam, a man named Herr Lagerman, whom she described as “a good-natured, chubby German.” From her position at De Bijenkorf, she pampered him a little—so he could occasionally bring something home to his girlfriend in return for small favors.

“We stayed open the whole war,” Lien recalled. “But toward the end, there were hardly any goods left, and entire departments were closed. We still had stockings, and occasionally some white goods would come in. Once we received a batch of wooden items—ashtrays, wooden spoons, that kind of thing. We had to put them on display to make it seem like we had something. When we had no more electricity, we took turns going to the attic—ten minutes of cycling to keep the generator running. You got 100 grams of cheese as a reward—so I pedaled like mad.”

Liberation

This horrific war eventually came to an end, and De Bijenkorf began to lick its wounds. Of the approximately 700 Jewish employees who had been forced to leave the company in 1940, only about 97 survived—many hundreds perished in the extermination camps. Around a hundred of the former Jewish employees returned to De Bijenkorf after the liberation. Frits Isaac returned in July 1945.

The German surrender also marked the end of the NSB-led management and the departure of other NSB members within De Bijenkorf. A few days after the liberation, Gé Schoorl in Rotterdam saw a prominent NSB staff member walking toward De Bijenkorf, apparently intending to simply resume work. Schoorl waited for him and told him bluntly that he had better turn around: there was no place for him in the company anymore. Gieskens and Graafstal, sensing the shift in power, did not return of their own accord.

On June 5, 1945, Gerrit van der Wal and Wolsheimer were appointed by the Military Authority in Amsterdam as trustees of De Bijenkorf, taking over from Benninga and Schoorl. Their first task was to purge the company of all NSB members. Soon, 102 employees were dismissed, having been confirmed as members or sympathizers of the NSB.

Frits Isaac was able to move back into his own house immediately—Van der Wal had looked after it during Isaac’s time in Switzerland. Hugo and Hans Isaac also returned to their positions shortly thereafter. Alfred Goudsmit returned a bit later, as he had to travel from the United States.

A decision still had to be made by the board and commissioners regarding Alfred Goudsmit’s reinstatement. It was especially thanks to the strong support of Frits Isaac during these discussions that his return was made possible.

During his forced exile in England and America, Goudsmit had not remained idle. In London, he contacted the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, and in consultation with them, he had relocated the official headquarters of De Bijenkorf—first to the Dutch East Indies, and later to Paramaribo. Had this relocation been deemed legally valid, all decisions made during the occupation would have been invalidated.

To prevent legal complications, a very unusual notarial deed was drawn up in December 1946, officially moving the company’s seat back to Amsterdam.

Back to the Old Nest

By the end of 1945, the executive board once again consisted of four members: Alfred Goudsmit, Frits Isaac, Gerrit van der Wal, and Engelbert Wolsheimer. In the key positions just below the executive level, not only had Hans and Hugo Isaac returned, but also Heinz Littaur, who, together with Jett Kerkhoff, would take charge of De Bijenkorf in The Hague.

Jett Kerkhoff was appointed to the branch management by Frits Isaac, in recognition of her extraordinary contributions during the war years and her steadfast resistance to the Germans.

Despite all efforts, the results for 1945 were disastrous. Turnover fell just as dramatically as costs rose. The shortage of goods would also continue well into the first full year of liberation.

In order to restore De Bijenkorf’s positive image, several high-profile exhibitions were organized. One of the most legendary was the “Wings of Victory” exhibition, which was majestically opened by Queen Wilhelmina.

sources

https://www.cultureelerfgoeddebijenkorf.nl/woii-verhaal/

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Goudsmit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Bijenkorf

https://www.tracesofwar.com/sights/24390/Memorial-Bijenkorf-Amsterdam.htm

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment