The Budy Massacre of October 5–6, 1942, remains one of the lesser-known atrocities of the Auschwitz concentration camp complex. Within the women’s penal company (Frauenstrafkompanie) at the Budy subcamp, approximately ninety French-Jewish women were beaten to death by SS guards and prisoner functionaries. This essay reconstructs the event, examines its causes and aftermath, and situates it within the broader framework of Nazi camp violence and gendered terror.

Introduction

While Auschwitz has become a universal symbol of the Holocaust, the network of its subcamps reveals the full extent of Nazi cruelty. Among them, the Budy subcamp (Wirtschaftshof Budy), located near Oświęcim, Poland, was initially established as an agricultural labor site and later served as a women’s penal company for prisoners accused of disciplinary offenses (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2023). Conditions in Budy were among the harshest in the entire Auschwitz system. Overcrowding, starvation, exhausting labor, and violent discipline characterized daily life.

In October 1942, this environment erupted into one of the most brutal episodes in the camp’s history: the mass murder of approximately ninety French-Jewish women. The so-called Budy Revolt, as described by SS commandant Rudolf Höß, was in reality a massacre rooted in systemic dehumanization and internalized violence.

Budy: A Penal Company for Women

The Budy subcamp was established in 1942 as part of Auschwitz’s agricultural operations. It also functioned as a Strafkompanie—a penal unit for women prisoners considered rebellious or undisciplined (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2024). The population included Polish, Slovak, and French-Jewish women, as well as German and Ukrainian prisoner functionaries (kapos) who were granted authority by the SS.

Men and women in the Budy subcamp were not assigned to work together. The SS designated different types of labor for each group. Male prisoners worked in farming and animal husbandry for twelve hours a day, from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Their tasks included raising pigs, cattle, and horses, as well as sowing grain and cultivating beets for animal feed. Beyond the hardships imposed by the harsh working conditions, prisoners—especially Jews—faced severe mistreatment and, in many cases, were killed by the SS or their overseers.

The penal company system was designed to destroy solidarity among prisoners. Kapos, often recruited from German criminal inmates, were given privileges in exchange for enforcing SS orders with brutality (Subcamps-Auschwitz.org, n.d.). The French-Jewish women, most of whom had been deported from Drancy and other internment camps in occupied France, were subjected to particularly harsh treatment. Their isolation, language barriers, and religious identity made them especially vulnerable to abuse.

The Night of October 5–6, 1942

The massacre began late in the evening of October 5, 1942. According to testimonies, a German prisoner functionary accused a French-Jewish inmate of attacking her with a stone while returning to the dormitory attic (Subcamps-Auschwitz.org, n.d.). Whether the incident occurred remains uncertain, but it served as the pretext for what followed.

The alarm was raised, and SS guards—along with German female kapos—stormed into the building. Over the next several hours, they bludgeoned, clubbed, and hacked to death around ninety women using sticks, rifle butts, and axes. Some victims were thrown from windows; others were beaten as they tried to escape into the yard. Those who survived the night were executed by phenol injections to the heart, a common method of killing prisoners at Auschwitz (Wikipedia, “Massacre in Budy,” 2024).

The ferocity of the violence suggests a collective psychosis induced by both Nazi indoctrination and the camp’s culture of cruelty. The victims’ bodies bore evidence of extreme mutilation. At dawn, the barracks floor was covered with blood and corpses—a grim testament to the depravity of the system.

Aftermath and Internal SS Response

When Rudolf Höß, commandant of Auschwitz, was informed of the massacre early on October 6, he ordered an internal investigation. The event was officially classified as a “revolt,” or Budy-Revolte, though evidence suggests there was no organized uprising (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2023).

A number of German prisoner functionaries were arrested. Six—including Elfriede Schmidt, known among inmates as the “Queen of the Axe”—were executed by lethal phenol injection for their role in the killings (Wikipedia, 2024). The punishment, however, was not motivated by a sense of justice but by SS concerns about maintaining control and preventing scandal within the camp hierarchy. No SS personnel were held accountable for the massacre.

The French-Jewish victims were buried in mass graves, their names largely lost to history. No comprehensive list of the dead exists, though memorial research continues at the Auschwitz Museum and associated archives.

Interpretation and Historical Significance

The Budy Massacre demonstrates how the architecture of Nazi terror relied on systemic moral collapse. The SS used internal hierarchies—kapos and block elders—to fragment the prisoner population, thereby deflecting blame and reinforcing the logic of domination. The massacre also underscores the gendered dimension of violence in the camps. Female prisoners, particularly Jewish women, were subjected not only to forced labor but also to humiliation, sexualized abuse, and gendered brutality.

The SS narrative of a “revolt” at Budy served as a convenient fiction, transforming victims into perpetrators and masking an act of mass murder as legitimate discipline. In reality, the massacre reflected a complete breakdown of order, where even the limited boundaries of camp “law” were discarded in a frenzy of sadism.

Memory and Commemoration

For decades, the Budy Massacre remained overshadowed by the larger narrative of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Only in recent years has it gained recognition as a significant event in Holocaust historiography. The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and the Subcamps of Auschwitz Project now commemorate the massacre annually on October 5, honoring the memory of the murdered women (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2023).

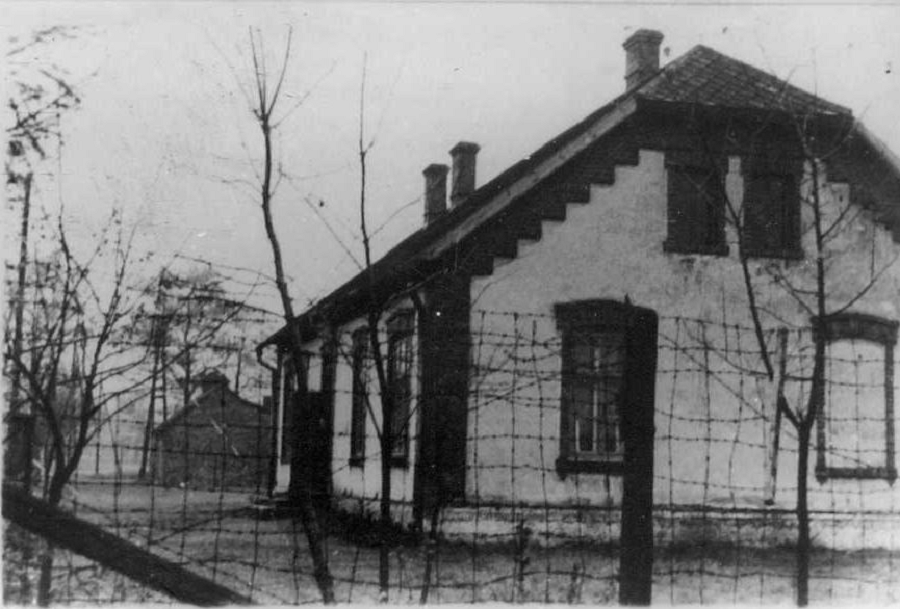

A surviving building from the Budy subcamp—once used as a barracks—still stands today. It has served various civilian functions since the war, including a kindergarten, symbolizing both the persistence of memory and the transformation of spaces once devoted to death.

The Budy Massacre encapsulates the essence of Nazi barbarity: not merely the industrialized extermination of millions, but the spontaneous, intimate violence that defined daily life in the camps. The 90 French-Jewish women killed in Budy were not victims of grand policy alone, but of a moral collapse engineered by a regime that weaponized cruelty.

To remember Budy is to affirm the individuality and humanity of those silenced by the machinery of terror. Their deaths, though once forgotten, now stand as a haunting reminder of how quickly civilization can dissolve into savagery when hatred and hierarchy replace compassion.

sources

https://subcamps-auschwitz.org/auschwitz-subcamps/wirtschaftshof-budy-strafkompanie/

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/budy-an-auschwitz-subcamp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massacre_in_Budy

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment