Before sharing the story of Frits Philips, I’d like to first touch on his family’s background

The patriarch of the Philips family is Philip Philips, a Jewish merchant from North Rhine-Westphalia who came to the Netherlands. Little is known about him. He was married to Rebecca van Crefelt.

Lion Philips (Zaltbommel, October 29, 1794 – there, December 28, 1866) was a Dutch tobacco merchant. He was the grandfather of Gerard and Anton Philips(Frits’s father), and a significant financial supporter of Karl Marx.

Here is an improved, more concise and clear version of your original text. I’ve preserved the historical accuracy while enhancing clarity, grammar, and flow for a smoother reading experience:

Frederik J. (Frits) Philips, president of the vast Philips Company, was the only director who chose to remain in the Netherlands when the German army invaded in 1940. While his colleagues fled to America, Frits felt a deep responsibility for both the continuity of his company and the safety of his Jewish employees, who were increasingly targeted by Nazi racial laws.

Frits faced a difficult balancing act. On one hand, he was compelled to meet German demands for increased production of war-related goods and reduced output of consumer items. On the other, he was determined to protect his Jewish workers from deportation. His “Jewish sympathies” were well known among German officials, and though he was forced to cooperate with a Nazi-appointed director, he never hid his views.

Eventually, his efforts to save Jewish lives and undermine the German war machine took precedence. In December 1941, he created two special units composed entirely of Jewish employees—one in Eindhoven, home to the main Philips plant, and another in Hilversum. These units, known as SOBU (Special Orders Bureau), performed simple technical tasks, often unrelated to their skills or training. Though segregated and subjected to lowered work standards, the employees accepted the arrangement as it spared them from deportation under the pretense that they were contributing to the war effort.

In a further humanitarian gesture, Frits arranged for free supplementary meals—“Philipsprak” (a mash of soup, potatoes, carrots, and meat)—to be distributed to workers with the approval of German authorities. By late 1941, 20,000 portions were served in Eindhoven alone, and in January 1943, Philips took over the preparation and distribution of these meals.

As the Nazis began concentrating Jews in Amsterdam in early 1942, the Hilversum SOBU group was ordered to relocate there. Instead, Frits secured permission for them to move to Eindhoven, consolidating the two groups. Throughout 1942, he tried to secure exit visas for these workers and their families, requesting \$2 million from Philips in New York to fund their emigration. Though the American branch had no objections, U.S. government approval was unlikely, and the plan was ultimately denied by the Germans in June 1943.

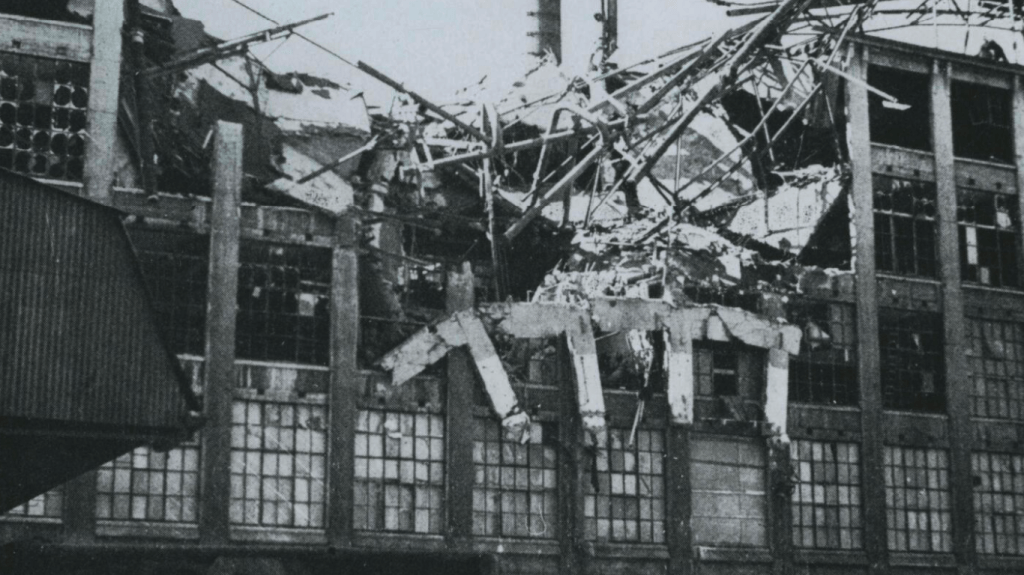

Meanwhile, Philips facilities were targeted by the Allies. A December 1942 RAF bombing severely damaged the plant.

In early 1943, Philips reluctantly agreed to set up a production line at Vught concentration camp, under strict conditions: workers had to receive extra hot meals (also called “Philipsprak”), and salaries continued to be paid—even to Jews in hiding, if their whereabouts were known.

Despite initial hopes that Vught wasn’t a deportation stop, those illusions were shattered on June 7, 1943, when Jewish women and children from the camp—though not yet from the Philips unit—were deported. In response, Philips intensified efforts to protect Jews by drafting more of them into the Philips-Kommando, believing their involvement in war production could shield them.

This strategy worked for a time. Even after the mass deportations in Amsterdam ended, the Philips-Kommando continued to operate until June 1944. However, the situation deteriorated. When a nationwide strike erupted in April 1943 to protest the deportation of Dutch soldiers, the Philips plant was shut down. The SS responded swiftly, arresting nearly the entire board of directors, including Frits, who remained imprisoned until September 20, 1943.

On his return, he found himself stripped of influence. In Vught, deportations resumed. By September 1943, only 400 of the 1,800 Jewish prisoners were allowed to stay; the rest were deported in waves. Philips pushed to retain workers by proving their value to the war effort, but it became increasingly difficult.

Finally, on June 2, 1944—just days before the D-Day landings—all remaining Jews in Vught, including SOBU members and children under 14, were deported directly to Auschwitz. On June 7, 1944, a transport of 496 people arrived—391 women, 90 men, and 15 children. Remarkably, 386 survived: 325 women arrived in Sweden on May 4, 1945; 11 women and 10 children reached Hamburg; and 40 men returned to the Netherlands. This reflects a 77.8% survival rate. Of the 87 SOBU members deported, 48 survived—a rate of 55.1%.

On July 20, 1944, Frits was warned that the SD was coming to arrest him. He escaped through a window and went into hiding. His wife, Sylvia Philips-van Lennep, managed to mislead the Germans for a time, but was eventually arrested and sent to Vught.

Frits Philips and his team’s efforts were driven not by ideology or gain, but by a genuine concern for the lives of their Jewish colleagues. After the war, Frits personally traveled to Gothenburg, Sweden, to reunite with the surviving women of the Philips group. It was an emotional reunion.

On July 18, 1995, Yad Vashem recognized Frederik J. Philips as Righteous Among the Nations for his courageous and humane actions during one of history’s darkest times.

Establishment of the Philips-Kommando

In early 1943, under pressure from the German occupying forces, the Dutch electronics company Philips was compelled to establish a workshop within the Vught concentration camp (Konzentrationslager Herzogenbusch) in the Netherlands. The workshop, known as the Philips-Kommando, was intended to contribute to the German war effort by utilizing prisoner labour to produce items such as radio tubes, dynamo torches, and other electrical components .

Frits Philips, who remained in the Netherlands during the occupation, negotiated certain conditions for the establishment of the workshop. Notably, he insisted that the workshop remain under Philips’ management and that the SS would not interfere with its operations. This arrangement provided a relatively safer environment for the prisoners working there, as the workshop was kept warm, dry, and offered better food compared to other parts of the camp .

Life and Work in the Kommando

Working in the Philips-Kommando was considered a relative privilege within the harsh realities of camp life. Prisoners assigned to the workshop were temporarily exempt from deportation to extermination camps, and the conditions, while still oppressive, were somewhat better than elsewhere in the camp. They received a daily hot meal, colloquially known as the “Philiprak,” and worked in environments shielded from the elements and SS brutality .

The workshop employed a diverse group of prisoners, including Jews, political detainees, and others. Efforts were made to protect educated and skilled prisoners by assigning them to roles such as drafting, accounting, and clerical work, which were less physically demanding and offered some protection from abuse .

Deportations and Survival

Despite the relative safety of the Philips-Kommando, the protection it offered was not indefinite. On 2 June 1944, all remaining Jewish workers in the Kommando were deported to Auschwitz. From there, many were transferred to other camps, including a subcamp of Groß-Rosen in Reichenbach, where they continued forced labour in factories such as those operated by Telefunken .

Remarkably, the survival rate among Philips-Kommando workers was higher than average. Of the 469 Jewish prisoners who had worked in the Kommando, 382 survived the war . This higher survival rate is attributed to the slightly better conditions and the efforts made by individuals within Philips to protect their workers.

Individual Stories

On the evening of December 5, 1941, Johnny van Dooren, along with his wife and father, is arrested for resistance activities. They had helped anti-fascists who had fled from Germany find a safe haven. His wife manages to talk her way out of trouble. Johnny and his father are sent to Camp Amersfoort. There, under the leadership of the SD (Sicherheitsdienst), they are treated particularly badly because they are communists. Over a year later, both are transferred to the newly established Camp Vught.

They are among the first group of battered men to arrive there. The living conditions are extremely poor. But Johnny is a survivor. At sixteen, his father had sent him out into the world with just a quarter in his pocket to gain life experience. He had always managed to get by.

As a communist, he is considered a threat to the state by the Nazis, which means imprisonment for the duration of the war. He constantly fears being sent to German camps. Thanks to his work for Philips, he is able to stay in Vught for a long time.

The Workers

Working at Philips

Johnny is one of the first to join the Philips Kommando. At long tables, he sits with dozens of prisoners sorting usable material from the rubble of the bombed factories in Eindhoven. “It was stupid work that had to be done with deadly seriousness,” says later technical leader Bram de Wit. In the same dusty barrack, other prisoners are busy copying damaged Philips documents.

Toolmaking Workshop

Due to his previous experience in an aircraft factory, Johnny is soon asked to set up a toolmaking workshop. He becomes the foreman of this small department, which later grows into a machine shop with many workers.

Nothing for the German war effort is produced in the toolmaking workshop, and that feels good. Johnny rather enjoys it there. In a smuggled letter to his wife Bets, he writes:

Development

Now, regarding my work: I have a department of 15 men here that I’m in charge of. We make the tools needed for the radio assembly line. They make 160 to 200 radio sets per day here. There is also a production line for electric shavers, about 150 of those are completed each day. All of this requires special tools, which we make here… I have a workspace of 20×18 meters, though that’s already too small… I don’t have to work, but I choose to, because I want to become as skilled as possible to earn more for you later… So in a way, my imprisonment still has some use, although I would gladly trade all these lessons for freedom and your nearness.

Leadership

Johnny is highly appreciated for the way he leads people as a foreman. He knows better than anyone how to keep up morale.

He tells new workers in a loud voice that they must work hard here. Then, more quietly, with a meaningful look, he adds: “With your eyes.”

Anyone who’s been at Philips for just one day understands that production is a secondary concern here.

A fellow prisoner in the workshop later says with admiration:

“Johnny had to lead a lazy and sabotaging bunch.”

He had witnessed firsthand the difficult position his foreman was in.

Foremen

‘Work Provision’

From the start, the Philips leadership makes an effort to employ as many prisoners as possible. When it becomes clear that producing war-essential goods can offer protection for the most endangered prisoners, this production is expanded.

In addition, work is done in the Philips workshop that is purely for the sake of providing occupation. For example, there is a department for hand-making paper clips, where older prisoners can work calmly and catch up on lost sleep. When this method proves very inefficient, Johnny’s workshop is ordered to produce 10 paperclip machines. There are also departments for cleaners, stokers, and even gardeners. The gardeners plant flowers around the Philips workshop, under the leadership of a well-known landscape architect.

Products

Food Packages

Working at Philips slowly helps Johnny regain his strength after the harsh early days in Vught and the suffering endured previously in Camp Amersfoort. He is now dry and warm, doing useful work, and there are no abusive guards around. Additionally, after a few weeks, prisoners are allowed to receive food packages.

His young wife goes to great lengths to send him weekly packages despite food rationing. She sends out begging letters to various companies to obtain food for prisoners without having to use ration cards.

On May 25, 1944, Johnny van Dooren and his father are transported with 264 men from the Philips Kommando to the Dachau concentration camp. There, Johnny is liberated in April 1945 by the American army. General Patton takes him along as a translator. His father was last seen in Bergen-Belsen camp, a week before liberation. He died there.

Eva Sanders is arrested in April 1943 after being betrayed for forging identity papers. Via the prison in Scheveningen, she ends up in Camp Vught. Her husband Lou arrives there the same day. They remain together in Vught for a long time afterward.

Eva lives in The Hague when, in August 1942, she is ordered to report because she is Jewish. With great difficulty, she obtains a forged identity card and lives for a while under the name Antje Feikema. She does not report herself. But she is soon betrayed and arrested. Her husband Lou, whom she had married six months earlier, voluntarily joins her. In prison, they are separated, but they are transported on the same train to Vught. There, Lou enters the Jewish men’s camp, and Eva the Jewish women’s camp. Once again, they are separated from each other.

About her first impressions of camp life in Vught, Eva says the following:

Living Barracks

In the Jewish women’s barracks, they are all crammed together: young mothers with small children, and also older and sick women. In one single space, diapers must be dried, food prepared, and meals eaten. The sleeping quarters are filled with hanging laundry and clothes, because there are no closets.

The Jewish families who arrived had brought luggage and food with them, which now lies scattered everywhere. They are still wearing their own clothes, and the men have not been shaved bald. From April 1943, large numbers of them are transported to Westerbork and then to unknown destinations. Eva Sanders watches in dread as the day approaches when she, too, will be sent away.

To Work

When women with seamstress experience are called up for a sewing kommando, Eva Sanders volunteers. It’s a lie—she doesn’t know how to sew. The actual seamstresses who didn’t volunteer are soon deported to Westerbork. For weeks, Eva pretends to know how to sew, afraid of being found out. Then she gathers her courage and begs a Philips supervisor to let her work there. She becomes one of the first Jewish women placed in the capacitors department.

“At Philips we worked very hard, 10 to 12 hours straight. When you got ‘home’ at 7 p.m., you still had to go to roll call.”

Daily Routine

Despite the hard labor at Philips, Eva enjoys the work because it comes with several benefits. One of the most important is that she sometimes gets to briefly see her husband Lou, who also works at Philips, during short breaks. But there are more advantages. She says:

“For Lou and me, getting extra food at Philips was crucial,”

because they received no food parcels from family or friends. All their Jewish acquaintances were either in camps or in hiding. They no longer had any contacts outside the barbed wire. Occasionally, they received a package arranged by civilians in Vught, delivered into the camp under the guise of the Red Cross.

Food

Women’s Visitation

On Sunday afternoons, there is sometimes “women’s visitation,” where Eva is briefly allowed to speak with Lou. When the small gate in the barbed wire around the Jewish women’s camp is opened by the Aufseherinnen (female guards), the men stream in. The conversations are often about trivial matters, as there are hundreds of people talking at once.

When, in the summer of 1943, most Jewish prisoners have left Camp Vught, “women’s visitation” is banned. The women’s camp is now largely empty and is filled with non-Jewish (resistance) women. From then on, it is called Frauen Konzentrationslager. From that point forward, even waving at each other is punishable. Eva makes sure to be careful.

Transport and Liberation

Eva Sanders is deported in June 1944 with the last transport of “Philips Jews” to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The group is not gassed upon arrival. Eva is selected as a Facharbeiterin (skilled worker) and sent to a camp near Reichenbach to work for Telefunken. After a heavy bombing raid in January 1945, they are forced to leave again. Following a grueling journey through various camps in Germany, Eva is liberated in May 1945.

Her husband Lou also survives the war—the only survivor of his entire family. The couple goes on to have two sons.

Bram de Wit, an engineer at the Provincial Water Board in Groningen, is arrested in February 1943, along with other senior provincial officials. They had openly encouraged their staff to resist certain measures imposed by the occupiers. After being held in the Groningen prison, he is sent to Camp Vught.

The Early Days

Engineer De Wit is immediately placed in the stone-carrying Kommando. The labor is exhausting. But he gets lucky. One day during roll call, prisoners with technical education are asked to step forward. They are placed on a list for work at Philips. The very next day, among the first 80 men of the Philips-Kommando, he is digging out usable parts from the rubble of the bombed Philips factories.

After a short time, Philips leadership asks him to take on the technical management of the workshop.

He walks around here with large strides,

A notepad clenched in his hand,

Eyes cast to the ground,

He tiptoes from tent to tent…

The Häftlinge Staff

Now in a leadership position, De Wit can help others as well. Together with Wissink, and Arie Heijkoop, he forms the Häftlinge-staff (prisoner staff) of the Philips Kommando. They ensure as many prisoners as possible are placed under the relatively safe umbrella of the Philips workshops. For instance, they arrange a place in the paperclip department for an elderly farmer from Groningen who had until then been shoveling sand all day. This old acquaintance had ended up in the camp for shouting “Long live the Queen!” in a town council meeting—betrayed by an NSB member.

The ‘Game’

Philips Leadership and Selection

Not everyone who wants to be in the Philips Kommando can be placed. Space is limited, and the selection committee is strict. Together with Philips leadership, De Wit selects new workers for the Philips Special Workshop every week.

“A hellish job…” he says later, because giving one person a spot means another is left out.

Smart Plan

One day, De Wit and Wissink come up with a plan: the Philips barracks should be guarded at night. This means they need night watchmen. In reality, this gives those “guards” a quiet place of their own to sleep safely and without fear of Kapos or SS men. De Wit forms lifelong friendships with some of them.

The Night Watch

A Trip in Prison Stripes

In June 1943, Philips manager Laman Trip arranges a lightning visit to the Apparatus Factory in Eindhoven for technical leader De Wit. Wearing his prison stripes, he gets to see how radio tubes are made. The accompanying guards are distracted with a hearty meal and lots of beer. After the visit, De Wit returns to the camp. He makes no attempt to escape.

High Visit

In the days before February 3, 1944, rumors swirl through Camp Vught: Himmler is coming! And indeed, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, the feared head of all concentration camps, arrives and inspects the Philips Kommando.

There are polished products and—sometimes falsified!—graphs on display to show production progress. Himmler is impressed and wants to know who organized it all.

Bram de Wit is called forward. Upon hearing his name, Himmler asks whether he is related to Johan de Witt, the Dutch Grand Pensionary from the Golden Age. De Wit neither confirms nor denies it:

“That’s what I was just trying to find out when I got arrested.”

Himmler has a short conversation with him and shakes his hand upon parting.

“…people in the camp talked about that handshake for days,”

writes David Koker in his diary.

Release and Liberation

A month later, on Himmler’s orders, De Wit and his colleagues from Groningen are released. Just a few days after, the German SD police come looking for him again. He flees to Eindhoven, where Philips offers him a job at the Construction Bureau. There, no one will think to search for him.

In September 1944, he witnesses the liberation of Eindhoven and joins the Allied forces, helping liberate northern Netherlands. After the war, he works abroad for Philips.

Anna Heringa is married to a doctor who joins the Medical Resistance during the occupation. In 1942, he is arrested, leaving Anna behind with four children. She takes in people in hiding, which poses a great risk. In February 1944, things go wrong. She is arrested, along with two Jewish women who were hiding with her. Someone betrayed her. After being held in prison in Amsterdam, she ends up in Camp Vught. Her children are left behind alone. The youngest is one and a half, the oldest 17 years old.

Upon arrival in Vught, she must hand over everything she has with her or is wearing. She is given a striped dress and wooden clogs. As a political prisoner, she must wear a red triangle on her dress. In the summer, the dress is replaced with a blue overall. Because she is a woman, her head is not shaved, but she must always wear a headscarf. In a letter to her children, she writes:

You should see me here, sitting like a factory girl in my ‘lovely’ striped dress and on my wooden shoes. The headscarf on, especially in the mornings and evenings during roll call—otherwise, you risk a ‘report.’ But don’t worry about me. I go about my business calmly and try not to draw attention.

Anna is placed in the Frauen Konzentrationslager (FKL), a part of the camp fenced off with barbed wire, where the female prisoners are held. In the early months, only Jewish women and children were housed here; now, only three barracks are still occupied by them.

Camp Mother

Anna Heringa is a cheerful woman, always helpful and caring toward others. That proves useful in the living barrack, which she shares with over 200 other women.

A young fellow prisoner recounts:

She was one of the women we considered a “camp mother.” Not all mothers automatically became camp mothers, nor did all young girls feel like camp daughters. I loved my camp mothers and cherish my memories of these wonderful women. There were more women like her. They made life a lot more bearable for the rest of us.

Living Barrack

In the barrack, this “camp mother” lives with all kinds of people who, under normal circumstances, would never have crossed paths: workers, intellectuals, and communists. They live under primitive conditions and are constantly afraid. Friendships form, but also many frustrations and conflicts.

Fights erupt over the distribution of food, a spot near the stove, or opening a window. Often, the law of the strongest prevails. Many things are stolen, even by people who would never steal under normal conditions. That’s why prisoners carry their few belongings—like a toothbrush or pencil—tied to a string under their clothes. Or in a handmade pouch, like Anna Heringa.

Daily Schedule

The Workday

Like everyone in the camp, Anna must wake up very early. The women wash themselves in a washroom that is far too small for so many people. Afterward, they get something that resembles coffee; a chunk of bread was already distributed the night before. Meanwhile, the Aufseherinnen (female guards) shout “schnell, schnell!” because the prisoners must be on time for morning roll call. Then the workday begins. Work continues from sunrise to sunset—so longer in summer than in winter.

At first, Anna is assigned to the sewing room, where she must repair unwashed prisoners’ clothing. When she falls ill, a friend puts in a good word for her at Philips.

Food

That’s how she ends up in the Philips Kommando and gets work on the “knijpkatten” (squeeze flashlights) assembly line. At Philips, extra food is distributed—the so-called Philipration. She is grateful for it because camp food is neither nutritious nor healthy. The Philips food helps keep her fragile health from declining further.

Leisure Time

The lives of female prisoners are largely controlled by the Aufseherinnen, the auxiliary guards. They roam in and around the living barracks, shouting and swearing, handing out punishments as they please. In the work barracks, they ensure no one talks or slacks off. But on Sunday afternoons, they have time off, just like the prisoners. Then there is a moment of peace.

In her free time, Anna writes letters and enjoys chatting with other women. For her friends, she makes small gifts out of scraps of cotton from the sewing room and unraveled threads of wool. She used to be an arts and crafts teacher and loves to create things.

Anna stays in Camp Vught for about six months. During the evacuation on September 5, 1944, she is deported with all the women to the Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany. Conditions in the women’s camp at Ravensbrück are horrific. Anna Heringa contracts typhus and dies in January 1945. Her husband and children survive the war.

When the Netherlands is occupied by German troops in May 1940, Juliette Cohen is working as a typist at Philips in Eindhoven. At the end of 1941, Philips establishes a special workshop, the SOBU, to protect its Jewish employees. Nevertheless, in August 1943, Juliette and the others are deceived by the SD and end up in Camp Vught.

Persecution of the Jews

Jewish girl Juliette Cohen is only 17 when, a few years before the war, she gets a job at Philips through an uncle. In a time of high unemployment, she is happy to be able to earn something, even if it means moving to Eindhoven with her mother. She enjoys working at Philips. In the evenings, she takes courses to become a fully qualified secretary.

At the end of December 1941, along with other Jewish employees at Philips, she is assigned to work at the SOBU, the Special Assignments Office. As a simple typist, she works at SOBU with people from all walks of life: scientists, managers, and factory workers. She feels protected there and learns a lot.

In the course of 1942, Juliette—like all other Jews in the Netherlands—receives a summons to report. Fortunately, she has a Sperre (an exemption) because she works at the SOBU. She and her mother are allowed to continue living in their home.

SOBU Group

As soon as the planned emigration of the SOBU group, via Spain to Curaçao, is discussed, she eagerly begins learning Spanish. Everyone has to prepare suitcases to be ready to leave the moment emigration is approved. Juliette types lists of the suitcase contents for the others. She recalls:

I typed the number of suits for Mr. So-and-so, the number of dresses for his wife, the number of diapers for the baby. We believed in those emigration plans. We even had the compartment layout for the train ready—and argued about it.

To Vught

At Vught, Juliette enters the Philips-Kommando along with the entire SOBU group.

The SOBU group is placed in a special SOBU barrack with their accompanying family members. Juliette’s mother also comes to Camp Vught, supposedly to await emigration. She follows her only daughter voluntarily. Due to her poor health, she is not required to work, unlike most other family members. As winter approaches, her illness worsens, and she is hospitalized.

When her mother becomes critically ill, Juliette is afraid to ask permission to visit her during work hours. A usually very strict Aufseherin (female guard) takes pity on her. When Juliette is marching back to the living barrack after work, the guard pulls her out of line and takes her to her mother. A day later, her mother dies. She is cremated in the camp.

Hans Maarschalk, the Philips civilian who visits the camp almost daily to supervise the SOBU group, manages to retrieve the urn with the ashes. He smuggles it out under his hat. A Philips employee keeps the urn safe for Juliette until after the war.

Fear and Faith

Jewish Transports

Meanwhile, Juliette lives in constant fear of being deported. Still, she continues to believe in Philips’ protection:

“I believed in Philips. Maybe it was naïve, but what else could you do?”

On June 2, 1944, the inevitable happens: all 500 Philips Jews are suddenly deported. In the dead of night, they are loaded into cattle cars. Later Juliette says:

“I didn’t know where we were going. You never talked about it. But four days later, when we were unloaded in Auschwitz, we saw it. Huge smoking chimneys, and it smelled like… human flesh.”

Miracle in Auschwitz

In Auschwitz, a “miracle” happens. Upon arrival, the entire group—known as the Philips-Gruppe—is not selected for the gas chambers but sent to a neighboring camp. After having a number tattooed on her arm, Juliette is sent a few days later, with most of her group, to Reichenbach as skilled workers for Philips. There, at Telefunken, they are assigned to resume making radio tubes. They are housed in a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen.

Death Marches and Liberation

When the Telefunken factory is heavily damaged in yet another bombing raid, Juliette and the other women are evacuated from Reichenbach in February 1945. In freezing cold, they are forced to march through the snow-covered Owl Mountains in search of new work and other camps. Many more journeys follow, by train and on foot, from camp to camp across Germany.

Eventually, in April 1945, Juliette and her fellow prisoners are liberated by the Danish Red Cross and taken in. Emaciated and filthy, they arrive in Sweden, where they are treated for infections and starvation. Once safe, the group spontaneously sings the Dutch national anthem, Wilhelmus.

After the War

Juliette Cohen survives even the final horrific months of the war and regains her strength in Sweden. In 1947, she returns to work at Philips.

“Thanks to Philips, I’m still alive,” she says.

After her marriage, she emigrates to South Africa.

The Story of Liba and Lilly Klafter: Survival Amidst Darkness

On 3 June 1944, a deportation train left the Vught concentration camp in the Netherlands for Auschwitz. The Germans, anticipating the Allied invasion of Western Europe, began evacuating Jewish prisoners. Among the deportees were Liba Klafter and her 14-year-old daughter, Lilly, from Amsterdam. This transport would later be known as the “Philips Deportation,” named for the group of Jewish forced laborers employed at the Philips factory in Vught.

Liba-Mitzi Hollander, born into a distinguished Viennese rabbinic family, met Jakob-Josef Klafter—originally from Karlsruhe, Germany—while visiting relatives in Amsterdam in 1926. They married and settled in the city, where Jakob ran a successful dental equipment import business from their four-storey home. Their daughter, Lilly, was born in 1929. Liba enjoyed a vibrant social life and often hosted gatherings in their home. In 1938, after the Anschluss, she helped rescue many relatives from Vienna, including her mother, Sheva (Swewa) Hollander.

With the German occupation of the Netherlands in May 1940, Jewish life quickly deteriorated. By the end of 1941, Jews were banned from public spaces, education, professions, and transport. They faced curfews, food restrictions, and were forced to wear the Yellow Star. Jakob’s business was placed under the control of an “Aryan” trustee. Liba and Lilly navigated daily life under increasing danger and scrutiny.

In May 1942, Jakob was arrested for suspected resistance activities. While Liba maintained contact with him by sending food and letters, she and Lilly faced growing threats. Their home was subject to constant raids, and the SS supervisor harassed them relentlessly. Liba eventually secured a hiding place. Each night, she and Lilly would remove their stars and disappear until morning. Eventually, they were forced to separate: Lilly was sent outside Amsterdam until her Jewish identity was discovered.

Despite pressure from family to flee to France and Spain, Liba refused to abandon her husband. Both mother and daughter were arrested during a daytime raid and taken to the Hollandsche Schouwburg (Municipal Theater), then used as a holding center for Jews. From there, they were deported to Vught in January 1943.

At Vught, Lilly worked as a seamstress and Liba joined the Philips factory, assembling radios with precision tools. When Lilly fell ill, Liba nursed her back to health. In February 1943, Liba’s mother Sheva was deported to Auschwitz and murdered. Jakob was deported to Sobibor five months later and also perished.

In June 1943, all children under 12 in Vught were sent to Sobibor and killed. Lilly, narrowly above the age limit, remained with her mother. Reflecting on her time in Vught, she recalled the separation of men and women, poor nutrition, and the emotional weight of the experience:

“Mother and I shared a bed. The food had pork fat and blood sausage, which I couldn’t eat… At home we weren’t very observant, but this was too much.”

In June 1944, the camp was evacuated. Liba and Lilly were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in what appeared to be ordinary passenger trains. Upon arrival, they were subjected to brutal processing. In the “sauna,” their hair was shaved, arms tattooed, and bodies disinfected. The smell of burning flesh, explained by veteran inmates, was the first hint of the horrors they were to witness. Lilly despaired, but her mother’s words stayed with her:

“We have to stay alive to tell the world what the Germans did to us.”

After seven weeks, Liba and Lilly were transferred to Reichenbach, where they worked grueling 12-hour shifts at the Telefunken factory, walking two hours daily to and from the camp. When Lilly contracted typhus, Liba carried her to work each day until she recovered.

As the Red Army approached, the women were forced on a death march. In snow and freezing temperatures, they were transported in open coal cars, shuffled between camps to avoid liberation. For the last four days of this journey, they were denied food and water. Many perished.

The journey ended near Hamburg, where survivors were forced to clear rubble from Allied bombings. On 1 May 1945, Liba and Lilly were finally liberated and sent to Sweden by the Red Cross to recover.

In 1946, Liba married a soldier from the Jewish Brigade of the British Army. That December, she and Lilly immigrated to Mandatory Palestine. Lilly joined the Haganah and served as a night guard in an orchard at Ayanot. In 1948, she enlisted in the IDF, serving as a communications officer and Red Cross interpreter during prisoner exchanges. She later married Ephraim Cohen, and they had three children.

In 1955, Lilly Cohen (née Klafter) submitted Pages of Testimony to Yad Vashem in memory of her father Jakob Klafter and her grandmother Sheva Hollander, preserving their names and stories for future generations.

sources

http://www.philips-kommando.nl/

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/229105/philips-kommando

https://www.yadvashem.org/exhibitions/last-deportees/vught-auschwitz-june.html

https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/righteous/4043449

https://www.nmkampvught.nl/during-and-after-the-war/

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment