The Netherlands is the country with the relatively highest number of Jewish victims in Western Europe. Of the 140,000 Jews, 107,000 were deported. Five thousand people returned from the camps, and approximately 20,000 survived in other ways, most of them in hiding.

The persecution and murder of the Jews during the Second World War is referred to as the Holocaust or the Shoah.

Here you will find information about the Holocaust, about the deportations and extermination, the lead-up, the looting of Jewish property, and the post-war handling of this catastrophe.

‘Work Expansion’

The term werk verruiming “work expansion” was a euphemism for the true goal of the deportations: to work to death those healthy enough to labor and to murder all others. At least 102,000 Jewish Dutch people were murdered or died from exhaustion and disease.

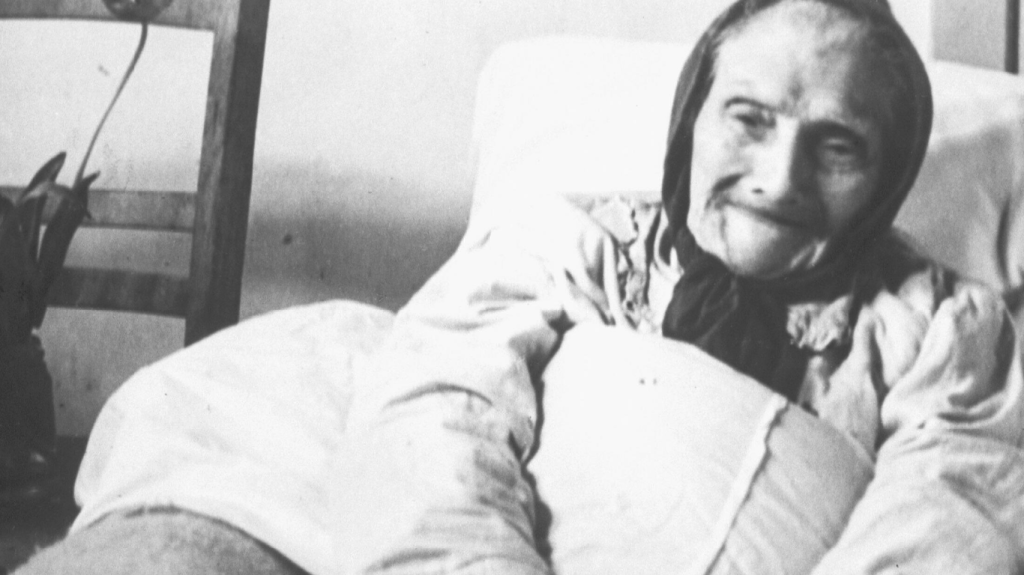

The photo shows Mrs. Klara Borstel-Engelsman. She was born in Amsterdam on April 30, 1842, and would be murdered in Auschwitz at the age of 102, on October 12, 1944.

The oldest Dutch victim of Nazi terror

Auschwitz-Birkenau

When the Nazis decided to murder all European Jews—after initially having pursued emigration as the goal—is not precisely known, but it must have been sometime in the fall of 1941. After necessary preparations, including the Wannsee Conference where the logistics of the mass murder were discussed, deportations from Western Europe began in July 1942. The first Dutch transport departed on July 16 to Auschwitz. Another 64 transports would follow.

Auschwitz was the destination for most of these transports. In the spring of 1942, two makeshift gas chambers had been installed in old farmhouses located on the grounds of the new Birkenau camp. That camp became the main site of mass murder, and most Dutch Jews were killed there. In 1943, four new gas chambers with crematoria were built, each capable of holding 1,200 to 1,500 people. Up to 120,000 people per month were murdered and their bodies incinerated.

Auschwitz-Birkenau Platform

The platform at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Photographer unknown. Collection of the Jewish Historical Museum.

Selections

Dutch Jews arrived at a platform near the freight station of Oświęcim (Auschwitz). Selections were made there by one of the SS doctors. All elderly people and mothers with young children were sent directly to the gas chambers. Men and women without children between the ages of 15 and 55 were temporarily spared and registered as Häftling (prisoners) in the camp. They were also tattooed with the infamous camp number on their arms. The others were taken on foot or by truck to one of the gas chambers, where they were murdered and their bodies burned. Their belongings were sorted and stored by other prisoners in a part of the camp called Kanada. These possessions were then shipped to Germany.

Prisoners selected for forced labor were, after a quarantine period, assigned to a labor detachment or sent to one of the satellite camps. Survival depended on the harshness of the work, but chances were slim. Furthermore, selections also took place in the barracks and during daily roll calls, where the weakest were sent to the gas chambers. In the end, fewer than 900 Jews returned to the Netherlands from Auschwitz.

Sobibor

In 1943, 19 deportation trains went from Westerbork to Sobibor instead of Auschwitz. Auschwitz was “overloaded” due to the ongoing murder of Jews from Thessaloniki. After that, a typhus epidemic broke out in the camp, which led the SS to temporarily suspend new transports. Sobibor was one of the camps of the so-called Aktion Reinhardt, established to exterminate Jews from the General Government (eastern Poland) and parts of western Ukraine. No selections were made at Sobibor—more than 99% of arrivals were murdered immediately upon arrival. The camp was small, only 400 by 600 meters. The areas with gas chambers were strictly separated from the rest of the camp where forced laborers were held, and from the SS camp. 34,313 Dutch Jews were killed in the gas chambers there.

There are 19 known Dutch survivors of this camp. The most well-known is Jules Schelvis, who was selected upon arrival for forced labor in the Dorohucza camp near Lublin.

He spent only a few hours in Sobibor. Selma Wijnberg, also Dutch, survived the legendary Sobibor uprising. On October 14, 1943, most of the prisoners—about 300—escaped the camp. The uprising was organized by Leon Feldhendler and Russian POW Alexander Pechersky. Most escapees were killed, but a handful survived, including Selma Wijnberg and her future husband, the Polish Jew Chaim Engel. After the uprising, the camp was closed and razed to the ground.

Other Camps

In 1943 and 1944, transports with Dutch Jews also went to the Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt camps—11 and 7 transports, respectively. These were so-called privileged camps (Vorzugslager) where Jews were held who might still be of use to the Germans. This included Jews with immigration certificates for Palestine and about 1,300 Jews who still had some financial means. They went to Bergen-Belsen because they were eligible for exchange with Germans held by the Allies. Only one such exchange transport went to Palestine—transport 222. The other prisoners remained in the so-called Sternlager.

Others went to Theresienstadt because the Germans still wished to delay their deportation for various reasons. Theresienstadt was also the destination for Jews with a 120,000-stamp—a coveted exemption for members of the Jewish Council and Jews whom the Germans deemed important for other reasons. There were also Jews who had served in the German army during World War I. Theresienstadt was labeled a “model camp” by the Germans and was not a concentration camp but a ghetto. It was used for propaganda purposes, such as during the visit of a Red Cross delegation, and a propaganda film was made. This film was directed by German Jew Kurt Gerron, who had been deported from Westerbork to Theresienstadt. However, even from this “model camp,” transports left for Auschwitz. Moreover, the living conditions in the overcrowded ghetto were poor—50,000 people lived there, and of the total 140,000 detainees, 35,000 died from hunger and disease.

That said, some aspects of a somewhat normal life were still possible in the ghetto. There was clandestine education for children, opportunities for cultural activities, and a limited form of Jewish self-governance: a council of elders or Judenrat.

Not only the anti-Jewish measures affected the lives of Jews.

In 1942, many Jews were forced to leave their homes even before the deportations began. From January 1942, many unemployed Jews (by then numerous due to the restrictions) were sent to Jewish labor camps. There were also evacuations from coastal cities to Amsterdam, and all non-Dutch Jews were sent to Westerbork.

Labor Camps

From January 1942, Jewish men were required to work in labor camps. The Jewish Council provided the names and addresses of unemployed Jews. From summer onward, it wasn’t just the unemployed—employed men were also summoned. On January 10, nearly 1,000 men departed for these camps, at a time of year when it was too cold to work the land. The camps were mostly in the eastern part of the Netherlands, and work ranged from harvesting potatoes to building roads. Beforehand, the men were examined by Jewish doctors at labor offices. These Jewish doctors often declared many men unfit for labor—out of solidarity or because the men had bought medical certificates. Consequently, non-Jewish doctors took over the examinations and declared virtually everyone fit, even those unfit to work. Between January and October 1942, about 7,500 men worked in over 40 labor camps. On September 28, 1942, 5,242 men were in the camps.

On October 2 and 3, 1942, all the camps were emptied at once, and the men were sent to Westerbork. At the same time, their families were taken from their homes in a major raid by Dutch and German police. They, too, were brought to Westerbork. This coordinated operation was organized by the Germans to create a large reservoir of Jews in Westerbork for deportation. Deportations had started in July, but meeting quotas set by Berlin proved difficult, so these men and their families were sent to Westerbork. More than 10,000 people arrived there as a result.

Evacuations

In January 1942, the occupying forces decided that Dutch Jews from certain cities had to move to Amsterdam. Evacuations started in Zaandam, followed by Arnhem, Hilversum, and Utrecht. Then many towns in North Holland and Zeeland followed. In Amsterdam, they were placed in three Jewish districts designated by the Germans: the Jewish quarter in the city center, the Transvaalbuurt in the East, and the Rivierenbuurt in the South.

At the same time, German Jews from these cities had to report to Westerbork. When Westerbork became full, German and later other non-Dutch Jews were housed in Asterdorp.

Jewish residents of evacuated cities had to hand over their house keys to the police, after which the Hausraterfassungsstelle came to register their belongings.

This was a sub-division of the Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung, established in March 1941 in Amsterdam to prepare and carry out deportations. Belongings were removed from homes by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg with the help of Dutch moving companies such as the Puls firm. Furniture and items from 25,000 homes were transported to Germany to be distributed to households affected by bombings. Some items were sold in the Netherlands. The empty houses were rented out to Dutch citizens. The most desirable homes were taken by Germans and Dutch Nazis.

A final forced relocation measure, after deportations had already long begun, came in early 1943: Jews living outside Amsterdam had to report to Camp Vught. Jewish workers from Amsterdam with economic exemptions were sent first, followed by Jews from the provinces after Rauter expelled all remaining Jews from those areas. Vught had factories on-site, giving the impression it was a labor camp. With this action, the Netherlands was officially considered “Judenrein” (cleansed of Jews) in the occupiers’ terminology. On paper, Jews were only still present in Amsterdam, Vught, and Westerbork. Ultimately, all Jewish prisoners from Vught were deported eastward via Westerbork—or in some cases, directly.

The Thirties

The events in Germany in the 1930s—the rise to power of Adolf Hitler, the increasing antisemitism, and Kristallnacht—did not go unnoticed by Dutch Jews. Still, many people thought that neutral Netherlands was safe and that such far-reaching exclusion could not happen here.

The NSB, the National Socialist Movement led by Anton Mussert, did gain 8% of the votes in the 1935 elections, but at that time, the movement was not yet truly antisemitic. By the time the NSB did become antisemitic, the party’s support had already dwindled. Everyday verbal antisemitism did exist in the Netherlands, but there was no real breeding ground for an explicitly antisemitic political group.

Refugees

After the takeover of power in 1933, but especially after the Kristallnacht of November 9 to 10, 1938, many Jews tried to flee Germany. The Dutch government reacted negatively to Jewish refugees: extra border control and strict measures concerning expulsions and work permits were intended to limit their number as much as possible. The estimated 20,000 Jews who were admitted had to be supported at the expense of the Jewish community.

In response to these events, the Committee for Special Jewish Interests (CBJB) was established in 1933. This committee was led by David Cohen and Abraham Asscher, who later became the leaders of the Jewish Council. Especially the Committee for Jewish Refugees (a subcommittee of the CBJB) took care of the reception of Jewish refugees from Germany. The Committee for Jewish Refugees provided passports and visas for people who wanted to travel further and gave advice and — if necessary — financial support to refugees who remained in the Netherlands.

At the end of 1938, the number of refugees admitted was drastically limited due to the strict refugee policy of the Dutch government. Moreover, all refugees now had to be housed in a central camp. The Westerbork refugee camp, which the Dutch government had built especially for this group in Drenthe, had to be financed by the Jewish community.

Survival: escape, hiding, resistance

Many attempted to escape deportations, but of course, it was extremely difficult to figure out which strategy offered the best chance of survival—if one even had a choice. Most first chose a “paper route” and tried to get on a list that, for some reason (Jewish origin not entirely certain; on the waiting list for an exit visa in exchange for money, gold, or diamonds, etc.), meant they did not have to be transported. Some lists were made more or less in good faith, while others were used by their creators solely for self-enrichment.

A small group—estimated to number between 1,800 and 2,700 people—managed to escape. The escape route was long and dangerous: overseas to England or overland to Spain and Switzerland. Among these refugees were the Palestine pioneers who fled across the border under the leadership of Joop Westerweel. Both Jewish and non-Jewish resistance groups were active in helping Jewish refugees.

Some were able to use the long waiting times in the Hollandsche Schouwburg to escape—through the intervention of others. Babies and small children did not stay in the Schouwburg but in a daycare center opposite the Schouwburg. That daycare was less well guarded, and several babies were smuggled out of this daycare and taken to hiding places by members of resistance groups. Walter Süskind, a German-Jewish refugee who worked at the Expositur in the Schouwburg, played a major role in this.

Children in the dormitory of the daycare opposite the Hollandsche Schouwburg, ca. 1942

Ultimately, hiding was the last hope for many, but finding hiding places was particularly difficult. Anyone caught hiding Jews risked deportation themselves, so few people were willing to do this. Moreover, it involved much more than just a hiding place. Those in hiding needed false identity papers, and ration cards and money had to be obtained to provide food for the hidden people. Various resistance groups were active in supporting those in hiding. Especially in the northern Netherlands, there were many hiding places, but also in South Limburg and elsewhere in the country, people were willing to shelter Jews. Sometimes one family sheltered several Jewish people in hiding. The Reformed Boogaard family in Nieuw-Vennep, who helped about 200 Jews hide, is very well known. In the end, about 24,000 to 25,000 Jews went into hiding, including 4,000 children. Of these, 16,000 to 17,000 survived the war.

Deportations

On June 26, 1942, Aus der Fünten informed the Jewish Council about the German plans to send Jews to Germany for “work expansion under police supervision.” This marked a new phase in the persecution of Dutch Jews. In the summer, large-scale deportations began. The schedule for the deportations and the number of people to be deported were determined in Berlin by Adolf Eichmann, who—after the death of Reinhard Heydrich in early June 1942—received his orders from Heinrich Himmler.

Based on the 1941 registration, the staff of the Zentralstelle made an initial selection. The Jewish Council was tasked with sending calls for “work expansion” in Germany to all men between 16 and 40 years old. Four thousand Jews had to go with the first transports, which took place from July 14 to 17, 1942. But people hardly responded to their summons and did not report. To still reach the number of four thousand, Jews (who were now easily recognizable by the star) were arrested on the streets. Jews already imprisoned in the Westerbork camp were also put on transports and deported to Auschwitz in Poland.

During July, seven more transports took place from Amsterdam to Westerbork. The gathering point for all these people was initially the Central Station but was later moved (perhaps to make it less visible to the general population) to the Hollandsche Schouwburg. It became increasingly common for Jews to refuse to report, resulting in quotas set in Berlin not being met. Therefore, raids were held again in August. This time the German police were assisted by the Amsterdam Police Battalion, a specially trained corps of pro-National Socialist members of the Dutch police. Streets were cordoned off, houses were searched, and those caught were taken away.

Exemptions

Attempts by the Jewish Council to reduce the number of Jews to be deported were unsuccessful. However, the occupiers allowed the Jewish Council to establish a system of exemptions, called ‘Sperres’ in German. These were intended, among others, for employees of the Jewish Council. When it became known that an exemption system was being used, there was a real ‘rush’ to the Jewish Council because many people tried to obtain an exemption through this organization. The Jewish Council itself had to select the 17,500 employees who would receive a stamp. In hindsight, there has been much criticism of this approach, especially regarding the selection criteria used: critics argue that nepotism and corruption played a role in the selection. In any case, the Sperre system was an effective tool for the occupiers to sow division. During 1943, the exemption lists ‘burst’ one by one, meaning the occupiers declared them invalid. Thus, the lists became an instrument used by the Germans to exempt certain groups of Jews and their families from deportation.

Besides these exemptions, there were other groups of Jews initially exempted from labor deployment, such as Jews married to non-Jews, certain categories of foreign Jews, and Jews who had been baptized Christian before January 1, 1941. Furthermore, there were the so-called ‘economic exemptions’—those who worked directly or indirectly for the German war effort. An example is the three hundred diamond traders and five hundred diamond workers selected to produce goods for Germany. All these exempted people received a special stamp (Sperre) on their identity papers and were ‘exempt from labor deployment until further notice.’ Many of the exempted were nevertheless persecuted and partly deported during the war.

Large-scale raids

Because almost no one reported voluntarily, most Jews were taken from their beds during night raids by German and Dutch police. The idea that there was selection for labor deployment quickly became untenable. Also, men had to go to the Jewish labor camps in Westerbork. Their family members were taken from their homes during a large-scale raid on October 2 and 3, 1942. German and Dutch police, the NSB, Dutch SS, German Nazi party officials, and Zentralstelle staff all helped. By the end of 1942, about 40,000 Dutch Jews had been transported to extermination camps in Poland.

At the beginning of 1943, Jewish hospitals, orphanages, and sanatoria became targets. On the night of January 21-22, 1943, Apeldoornse Bos, a Jewish psychiatric hospital in the Veluwe area, was ‘emptied.’ Led by Aus der Fünten, Apeldoornse Bos was searched, defenseless patients were beaten and mistreated, loaded into trucks and later into cattle cars. The train with patients and nurses went directly to Auschwitz, where almost everyone was immediately gassed upon arrival. On March 1, 1943, a raid took place on the Jewish Invalide, the large Jewish care institution in Amsterdam. Old, weak, and sick patients were rounded up and deported by the SS.

In May, the Jewish Council had to start selecting its own people. Seven thousand people were summoned, but too few appeared. Therefore, a large raid followed on May 26 in the Jewish quarter. On June 20, there was another raid, and several Jewish Council employees whose stamps had been invalidated were arrested. After another raid on July 23, mainly holders of the 120,000 stamp remained—the best stamp to have for members of the Jewish Council and other privileged Jews. On September 29, 1943, the last raid took place in Amsterdam. The occupiers now called the capital ‘Judenrein’ (cleansed of Jews).

sources

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/546947/de-holocaust-in-nederland

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Holocaust_in_the_Netherlands

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-netherlands

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment