Maastricht is one of the most beautiful cities in the Netherlands. It’s in the southeast of the country in the Province of Limburg. It is very dear to me. I was born only a few miles away from it, but it is the city where my father was born. A few years after the war, my mother worked in the Sphinx factory in Maastricht, where they produced ceramics mainly for bathrooms.

Needless to say, I have a strong connection to the city.

The first mass arrest of Limburg Jews took place on 25 August 1942. Jews under the age of sixty received a summons on 24 August to report for “labour-expanding measures.” They had to gather a day later in a school building on Prof. Pieter Willemsstraat 39 in Maastricht. The summoned Jews, therefore, had one day to go into hiding or to get a deferment. Fewer than 300 people left for Camp Westerbork instead of the planned 600. Most of the detainees were put on transport to the East on 28 August. This was the first deportation train to stop in Cosel. Men between the ages of 16 and 50 were taken off the train and taken to Jewish labour camps. The majority of the women, children, and men between the ages of 50 and 60 were gassed in Auschwitz on 31 August 1942.

The deportation of Jews from Maastricht, a city in the southern part of the Netherlands, represents a profoundly tragic and significant chapter in the Holocaust during World War II. Under Nazi occupation, the Jewish population of Maastricht, like those across the Netherlands and Europe, faced systematic persecution, deportation, and extermination at the hands of the Nazi regime. This essay explores the context, process, and devastating consequences of the deportations from Maastricht, shedding light on one of the darkest periods in modern history.

The Nazi occupation of the Netherlands began on May 10, 1940, when German forces invaded the country as part of their more extensive campaign to conquer Western Europe. Despite Dutch neutrality, the Netherlands quickly fell to the Nazis, and by May 15, the Dutch government surrendered. The occupation marked the beginning of a brutal regime that would last for five years. During that time, the Nazis implemented anti-Jewish policies and laws that stripped Jewish citizens of their rights, livelihoods, and, eventually, their lives.

At the time of the Nazi invasion, approximately 140,000 Jews lived in the Netherlands, including a small Jewish community in Maastricht. The city, located near the borders of Belgium and Germany, had a rich history of Jewish life dating back centuries. However, under Nazi rule, this vibrant community would be targeted for destruction.

The persecution of Jews in the Netherlands began almost immediately after the Nazi occupation. The Nazis implemented a series of anti-Jewish decrees that mirrored those imposed in Germany and other occupied territories. These measures included the registration of Jews, the confiscation of Jewish-owned businesses, the forced wearing of the yellow Star of David, and the segregation of Jews from the rest of Dutch society. Jewish children were expelled from public schools, and Jewish professionals were banned from their respective fields.

In Maastricht, as in the rest of the Netherlands, these policies led to the isolation and marginalization of the Jewish population. Jewish families were forced out of their homes, and many sought refuge in hiding or fled the country. However, escape was harrowing, and the majority of Jews in the Netherlands remained trapped under Nazi control.

The next step in the Nazi plan was the systematic deportation of Jews to concentration and extermination camps. The first significant wave of deportations from the Netherlands began in the summer of 1942, and Maastricht’s Jewish population soon became a target of these horrific operations.

The Nazi SS, under the direction of Heinrich Himmler, played a central role in organizing and carrying out the deportation of Jews from the Netherlands, including Maastricht. The SS, responsible for overseeing the concentration camps and implementing the Final Solution, coordinated the arrests, transportation, and eventual murder of Jews across Europe.

In Maastricht, Jewish residents were rounded up by local collaborators and SS officers. These arrests were often carried out with brutal efficiency, with families given little to no warning before being taken from their homes. They were transported to local collection points before being sent to the Westerbork transit camp in the northeastern part of the country. Westerbork served as a holding camp for Jews from across the Netherlands, and it was from here that they would be deported to extermination camps in Poland, such as Auschwitz and Sobibor.

The deportations from Maastricht, like those across the Netherlands, were marked by terror and cruelty. Jews were crammed into overcrowded trains, often under horrific conditions, and sent on a journey that most would not survive. Many families were separated during this process, never to be reunited. The transports from Westerbork to the death camps were relentless, with thousands of Jews being sent to their deaths each week.

The Jewish community of Maastricht, like so many others in the Netherlands, was decimated by the Holocaust. Before the war, the city had a Jewish population of around 600 people. By the end of the war, only a small number had survived. The majority of Maastricht’s Jews were deported to Auschwitz and Sobibor, where they were murdered in gas chambers or died from starvation, disease, or forced labor.

The destruction of Maastricht’s Jewish community was part of the broader genocide that claimed the lives of approximately six million Jews across Europe. In the Netherlands, the Holocaust resulted in the deaths of around 102,000 Jews out of the pre-war Jewish population of 140,000. This staggering loss was among the highest death rates of any country in Western Europe, a grim testament to the efficiency of the Nazi extermination machine.

The Holocaust left an indelible mark on the Netherlands, and the memory of the deported Jews of Maastricht continues to be honored today. In Maastricht, as in other Dutch cities, memorials have been erected to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. These memorials serve as a reminder of the horrors of the Nazi occupation and the importance of remembering the past to prevent future atrocities.

In addition to physical memorials, educational initiatives have been established to teach future generations about the Holocaust and the importance of tolerance and human rights. The story of the Jews of Maastricht, their suffering, and their resilience remains an essential part of this educational effort.

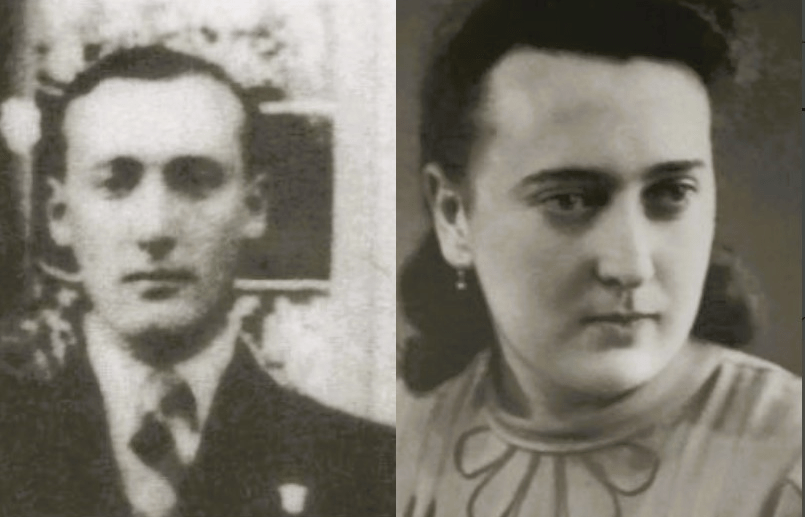

The Zeligman Family

Like nearly all Jews during the war, Eva and Albert Zeligman from Meerssen were summoned to report for deportation at Maastricht Railway Station. On the day of departure at the end of August 1942, Eva pretended to be seriously ill and unable to travel. The Nazis believed her, and they ordered Mr and Mrs Zeligman to return home.

Albert Zeligman, who ran a butchery, was convinced that the German occupiers would summon them again for deportation. He had also told that to Joseph Mommers, a baker from Bunderstraat who delivered bread to the Zeligman family.

Joseph Mommers and his wife Anna offered to help them if it came to that. On a wintry evening in February 1943, Mr and Mrs Zeligman stood at the door of the Mommers bakery. They were allowed in and then hid in the attic for nineteen months.

The couple survived the war, but their two children, Herbert and Hildegard, did not.

The Nazis had taken the Zeligman children out of the parental home on 25 August 1942. Their fate had been decided in advance. Uncle Salomon, who lived with the family, did not survive the war either. He was rounded up in April 1943 and gassed in Sobibor one month later.

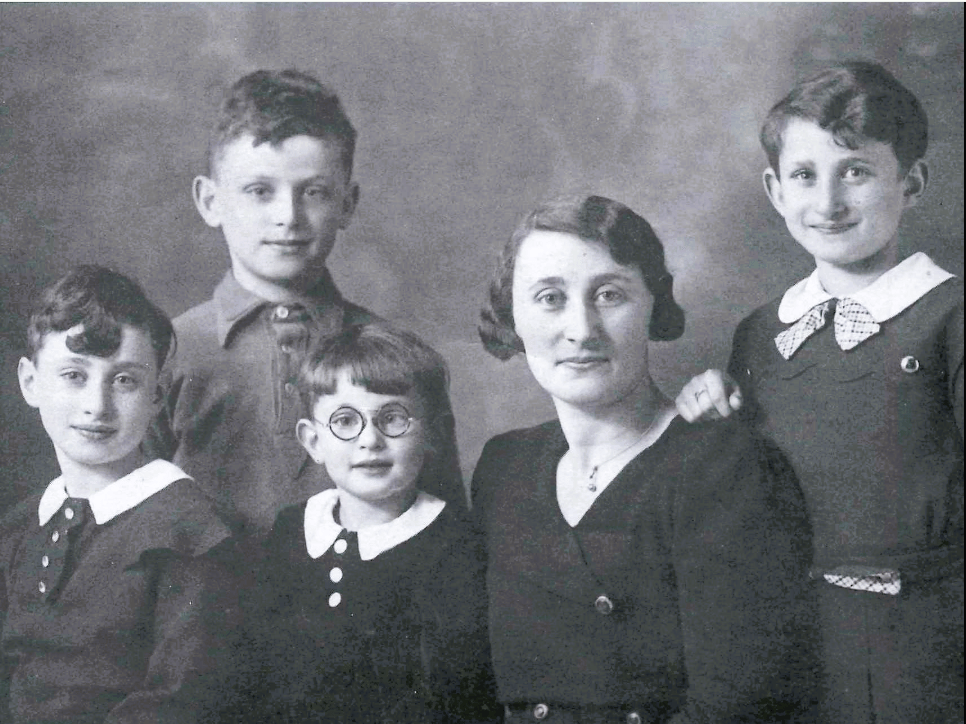

The Cohen Family

As I mentioned, I was born a few miles away from Maastricht in the town of Geleen. On 25 August 1942, approximately 20 Jewish citizens from Geleen were brought to and then deported from town hall by the Germans. The Cohen family were among them. They were then taken to Maastricht.

The Cohens were a family of six: Simon, the Father, and Esthella Carolina Cohen-ten Brink, the mother. The Daughters were Josephine, age 12, and Henny, age 16.Frieda age 17 and 1 son Gerrit. Gerrit is the only one who survived the war. They were put on transport to Westerbork on the 25th of August, 1942. On the 28th of August, they left Westerbork for Auschwitz, where they arrived on the 30th of August.

Simon, Esthella Carolina, Josephine, and Frieda were all murdered on the 31st of August 1942. Henny was murdered on the 26th of September 1942.

Sources

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/nl/page/137528/simon-cohen

https://www.liberationroute.com/it/pois/944/people-in-hiding-at-the-bakery

https://jck.nl/en/jewish-communities/maastricht

https://www.oorlogsbronnen.nl/tijdlijn/ae0946fb-6336-4db7-894a-89fe1a8c081c

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment