On February 11, 1941, the NSB member Hendrik Koot was injured fatally during a brawl at Waterlooplein. The official reports on the incident remained lost for decades.

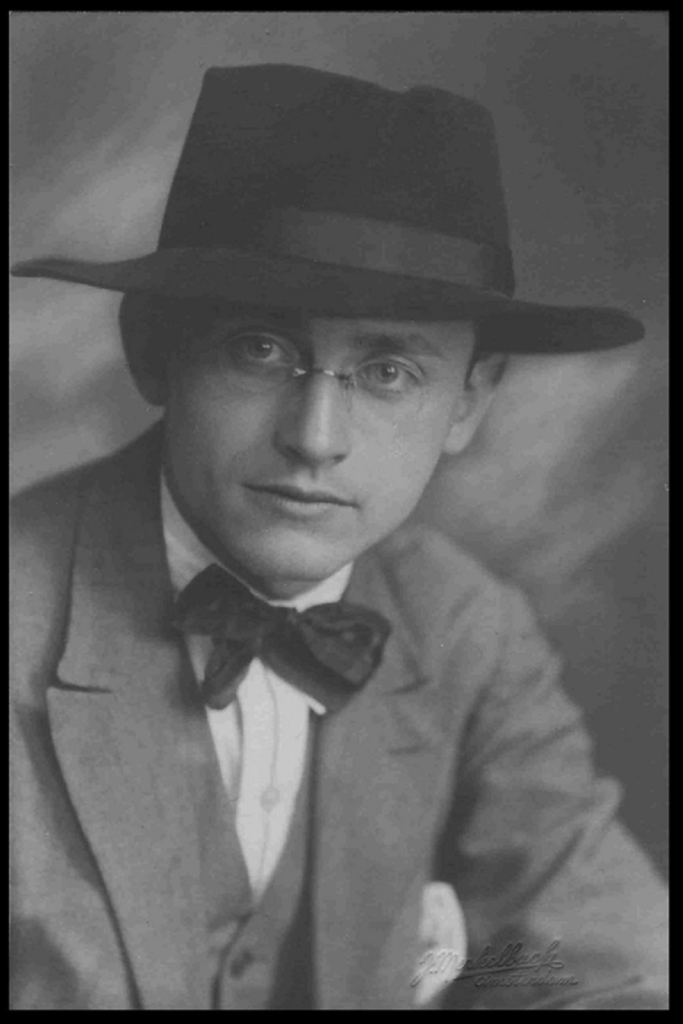

Koot

Hendrik Koot was a member of the Weerafdeling (WA), the paramilitary wing of the NSB. Since late 1940, WA members had been intimidating and assaulting Jewish residents of Amsterdam. On February 11, 1941, around 45 WA men marched through Waterlooplein, singing. A resistance group of Jewish and non-Jewish Amsterdammers fought back. The fight involved iron bars, sticks, and clubs. Hendrik Koot was left unconscious in the street and died on February 14 at the Binnengasthuis hospital.

Brutal Attack

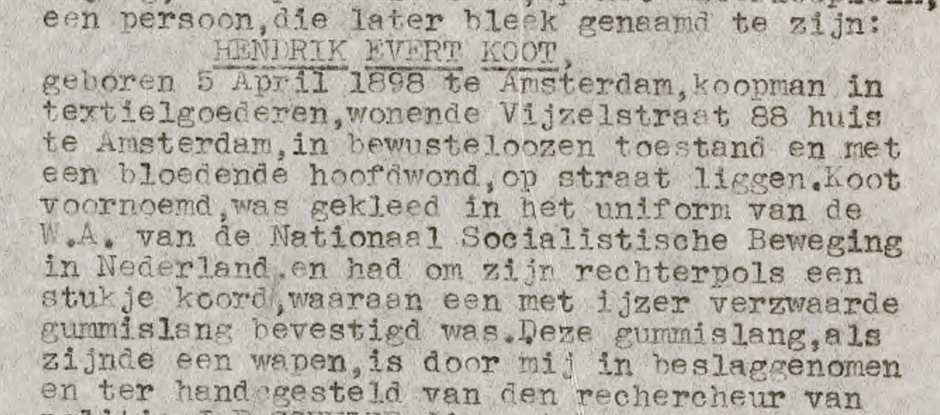

According to the NSB, Jews had slaughtered Koot in a brutal manner, claiming he had suffered countless injuries and that his larynx had been bitten off. In reality, Koot had only a severe head wound. The NSB also claimed that Koot was unarmed. However, police brigadier Pieter Oudheusden found “a piece of cord around his right wrist, attached to a rubber hose weighted with iron.” Koot had turned a piece of garden hose into a deadly weapon known as a ploertendoder (a type of club).

After Koot’s death, Hanns Albin Rauter, the Austrian-born SS and Police Leader in the Netherlands wrote an op-ed in the NSB newspaper Volk en Vaderland, sensationalizing the act with a grotesque claim: “A Jew had ripped open the victim’s artery with his teeth and sucked his blood out.” Historians note this as an “obvious allusion to ritual murder.” Dutch historian Jacques Presser argued that in their lurid descriptions, the Nazis revealed “their own bestiality rather than describe the actual facts.” Notably, these sensationalized details are absent from police reports.

Disappearance of the Files

The sensitive case file containing the official reports on Koot’s death disappeared shortly after the incident. However, during an inventory of the Amsterdam Municipal Police archives, it was found among personnel records from the 1930s, which allowed it to be preserved. Other official reports from that period were destroyed.

The investigator reported that he found Koot in an unconscious state

A few days after Koot’s death, unidentified vandals smashed the windows of the Koco ice cream parlor, a business owned by two Jewish refugees from Germany. In response, Jewish and non-Jewish customers formed a defense group to protect the store. When the Ordnungspolizei raided the shop on 19 February, they were met with a spray of ammonia.

Raids

Himmler, Seyss-Inquart, and Rauter decided to set an example: the first razzia (raid/mass arrest) of Jews became a reality.

On the afternoon of Saturday, February 22, 1941, a column of German trucks appeared near Waterlooplein and sealed off the entire area. In a ruthless operation, young Jewish men were rounded up and driven to Jonas Daniël Meijerplein. The arrests continued the following day.

In total, the Germans deported 427 Jewish men between the ages of twenty and thirty-five to Camp Schoorl.

Eight of them were released but later deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp and subsequently to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Only two survived.

The owners of the Koco ice cream parlor faced severe punishment. Ernst Cahn was executed by the Germans on March 3, 1941, at the Waalsdorpervlakte, a site in the dunes near The Hague. Alfred Kohn died in Auschwitz.

February Strike

On February 25, 1941, a general strike erupted in Amsterdam, and other cities, in response to the first major Nazi raid, during which hundreds of Jews were deported to Mauthausen.

That morning, trams remained in their depots, preventing many workers from reaching their jobs. Shops, offices, and industries shut down in protest against the brutal anti-Semitism of the occupying Nazi forces. The strike quickly spread to other cities, including Haarlem, Hilversum, Utrecht, and towns along the Zaan.

As the day progressed, the occupiers took harsh measures to suppress the uprising. Nine people were killed, and several dozen were injured. In the following days, 300 communists who had helped organize the strike were arrested, and 18 were executed in retaliation.

The February Strike was the only large-scale, open protest against the persecution of Jews in all of occupied Europe. However, the severe reprisals instilled widespread fear, and no further strikes followed.

Street paver Willem Kraan and sanitation worker Piet Nak were the most well-known initiators of the protest strike. Their goal was to mobilize the tram services, sanitation workers, and the Public Works Department into striking, believing that the rest of the city would naturally follow.

On the morning of February 25, 1941, the trams quickly came to a halt. From there, the strike spread rapidly across the city.

Harsh Repression

On the second day of the strike, the Germans responded brutally. They fired indiscriminately, while the mayor threatened severe punishments and mass dismissals.

• 18 strikers were executed a few weeks later

• 22 were imprisoned.

• Over 70 lost their jobs.

• Amsterdam was fined 15 million guilders.

Het Lied der Achttien Dooden” is a poem written by Jan Campert (1902-1943) in response to the execution of eighteen resistance fighters on March 13, 1941, at Waalsdorpervlakte.

On January 12, 1943 at 13:30 Jan Campert died in the Neuengamme Concentration Camp of pleurisy.

Translated version of the poem

The Song of the Eighteen Dead

A cell is but six feet long

and hardly six feet wide,

yet smaller is the patch of ground,

that I now do not yet know,

but where I nameless come to lie,

my comrades all and one,

we eighteen were in number then,

none shall the evening see come.

O loveliness of light and land,

of Holland’s so free coast,

once by the enemy overrun

could I no moment more rest.

What can a man of honor and trust

do in a time like this?

He kisses his child, he kisses his wife

and fights the noble fight.

I knew the task that I began,

a task with hardships laden,

the heart that couldn’t let it be

but shied not away from danger;

it knows how once in this land

freedom was everywhere cherished,

before the cursed transgressor’s hand

had willed it otherwise.

Before the oath can brag and break

existed this wretched place

that the lands of Holland did invade

and for ransom her ground has held;

Before the appeal to honor is made

and such Germanic comfort

our people forced under their control

and looted as a thief.

The Catcher of Rats who lives in Berlin

sounds now his melody,—

as true as I shortly dead shall be

my dearest no longer see

and no longer shall the bread be broke

and share a bed with her—

reject all he offers now and ever

that sly trapper of birds.

For all who these words thinks to read

my comrades in great need

and those who stand by them through all

in their adversity tall,

just as we have thought and thought

on our own land and people—

a day does shine after every night,

as every cloud must pass.

I see how the first morning light

through the high window falls.

My God, make my dying light—

and so I have failed

just as each of us can fail,

pour me then Your grace,

that I may like a man then go

if I a squadron must face.

David was the last survivor of the February group to perish in Mauthausen. He endured almost a year of unimaginable hardships and brutality before succumbing.

David Estella Zilverberg was one of the courageous Jewish men involved in the clashes at Waterlooplein, which led to the death of NSB member Hendrik Koot. Below is his story.

David Estella Zilverberg

Amsterdam, 11 April 1916 – Mauthausen, 5 February 1942

Address: Valkenburgerstraat 10-III

Occupation: Typesetter

David Estella Zilverberg, known as Lard, was the eldest son of Jacob Zilverberg and Mirian Cohen. His sister Estella, born after him, was the only girl in the family, followed by four younger brothers: Isaac Dina, Philip Margot, Mozes, and Franciscus Cornelis. The Zilverberg family had deep roots in Coevorden, but Lard’s grandfather moved to Amsterdam from Overijssel in 1889.

Lard grew up in a communist household in the Nieuwmarkt neighborhood. A contemporary noted that the Zilverberg home had “many books” on its shelves. He attended six years of primary school in the neighborhood before working as an apprentice wallpaper hanger. Later, he trained under his father, Jacob, a sign painter and commercial artist, who adapted the family’s long-standing profession of painting into a creative trade. Jacob cycled through Amsterdam with his lettering kit, offering his services to shop owners. It was not a lucrative job. Lard, who had a talent for drawing and painting, assisted his father before becoming a typesetter himself.

Boxing and Resistance

Besides his work, boxing was a major part of Lard’s life. He trained at Maccabi, a club that also included non-Jewish members. Despite his small stature, his fierce fighting style earned him the Dutch flyweight championship in 1938. His brothers Philip and Isaac (“Kickie”) were also skilled fighters. Many Jewish men in the old Jewish quarter trained at local boxing clubs, including well-known figures like the Brander brothers, Bennie Bluhm, and Bennie Bril. Coming from poor working-class families, boxing gave them a way to prove themselves through intelligence, technique, and perseverance. Club fees were low, and trainers often waived them for those who couldn’t afford to pay.

Lard’s boxing skills, political awareness, and sense of justice defined his life. By the late 1930s, he had already clashed multiple times with NSB members, posted anti-fascist posters around the city, and painted slogans like “Fascism is murder” on walls. Near Coevorden, where his family had roots, he helped smuggle refugees across the border to safety in Amsterdam.

When direct attacks on Jewish businesses and individuals increased in late 1940 and early 1941, Jewish resistance groups formed. Lard and his brothers, living on Valkenburgerstraat, joined these self-defense groups, which also included non-Jewish fighters. They patrolled the streets in small groups, driving out Nazis from their neighborhood. As historian Jacques Presser put it:

“They did not seek out their enemies, but they refused to be slaughtered without resistance.”

February 1941 & Arrest

The violent clash on February 11, 1941, in which WA member Hendrik Koot was fatally wounded, was Lard’s last major fight. After the brawl, he was arrested by German police along with 18 others. He was still carrying the iron bar he had used in the fight. Along with his brother Philip and neighbor Mark van West, he was forced to pose for a propaganda photograph, which the Nazis used to falsely accuse the Jewish fighters of brutal crimes.

Some of the arrested men were later released, including Lard’s brother Philip. However, Lard’s fate remains unclear. No records of his imprisonment exist in Amsterdam police archives or in Scheveningen Prison (“Oranjehotel”).

According to Buchenwald camp records, Lard was arrested during the February 22, 1941 razzia and sent to Camp Schoorl. On February 27, he and 387 other Dutch-Jewish men were deported to Buchenwald and later, on May 22, to Mauthausen. He was the last survivor of those arrested during the February raids but ultimately died on February 5, 1942 after nearly a year of enduring the brutal conditions in Buchenwald and Mauthausen.

Family Tragedy

Lard was not the only member of his family to perish. His fellow resistance fighters Meijer Bloemendaal, Izak Montezinos, and Abraham Wijnschenk died before him, as did his 20-year-old brother Isaac, arrested during a June 11, 1941 razzia and killed in Mauthausen on September 26, 1941.

His parents, Jacob and Mirian, along with his brothers Philip, Mozes, and Franciscus, were all murdered in Nazi extermination camps.

The only survivor of the Zilverberg family was his sister, Estella Froukje.

Sources

https://www.amsterdam.nl/stadsarchief/stukken/oproer/februaristaking/

https://www.amsterdam.nl/stadsarchief/stukken/tweede-wereldoorlog/verdwenen-dossier/

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/635/february-strike

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/86868/david-estella-zilverberg

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Februaristaking

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Het_lied_der_achttien_dooden

https://www.annefrank.org/en/timeline/71/razzia-on-jewish-men-in-amsterdam/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hendrik_Koot#cite_note-Warmbrunn-6

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to tzipporahbatami Cancel reply