Adolf Hitler’s 56th birthday was on April 20, 1945, during the final days of World War II. By this time, Nazi Germany was collapsing under the Allied advance. Hitler spent the day in his bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, surrounded by close aides. Despite the bleak situation, some staff attempted a subdued celebration with a birthday cake and brief well-wishes. Others had another birthday surprise for him.

On the night of April 20, 1945—just days before the liberation of Nazi Germany—a war crime of unfathomable cruelty unfolded in the cellar of a school in Hamburg. Twenty Jewish children, already victims of brutal medical experimentation at the Neuengamme concentration camp, were hanged in the basement of Bullenhuser Damm school by members of the SS.

There were no survivors among the 20 children. But fragments of what happened emerged in the postwar years through court testimony and painstaking journalistic work.

Soviet prisoner Walter Eisenbraun, one of the few people left alive who had worked in the area, later testified to the conditions in the camp and the school. He recalled hearing about the fate of the children and described the atmosphere of secrecy and fear in the final days of the war.

One of the guards involved in the killings, SS-Unterscharführer Ewald Jauch, confessed during postwar trials that the children were executed simply to cover up the experiments. His chilling testimony included the fact that the children cried and resisted when they realized what was happening.

Journalist Günther Schwarberg, who brought the case to public attention in the 1970s, interviewed relatives of the children and tracked down surviving Nazis involved. In his 1983 book The Murders at Bullenhuser Damm, he wrote:

“There were no cries for help, only the quiet shuffling of feet on stone steps… And then there was silence. One by one, twenty little lives were extinguished.”

In April 1945, as the British army advanced toward Hamburg, twenty Jewish children were taken to the basement of a former school on Bullenhuser Damm. On April 20, while still asleep from being drugged with morphine, they were hanged from wall hooks.

On April 20, 1945—Adolf Hitler’s fifty-sixth birthday and just days before the end of the war—SS physician Kurt Heissmeyer and SS-Obersturmführer Arnold Strippel ordered the murder of the children in a final attempt to destroy evidence of their medical experiments, as Allied forces closed in on Hamburg.

SS physician Kurt Heissmeyer sought to attain a professorship by presenting what he claimed was original medical research. His central hypothesis—already disproven by established science—was that injecting live tuberculosis bacilli into human subjects could function as a vaccine. Another component of his experiments was grounded in pseudoscientific Nazi racial theory, which falsely claimed that race influenced susceptibility to tuberculosis.

To “prove” his theory, Heissmeyer injected live tuberculosis bacilli directly into the lungs and bloodstream of individuals whom the Nazis considered Untermenschen (subhumans)—primarily Jews and Slavs, whom they viewed as racially inferior to Germans.

Heissmeyer secured the facilities and human subjects for his experiments through high-level connections, including his uncle, SS General August Heissmeyer, and SS General Oswald Pohl, a close associate.

The initial experiments were conducted on Soviet and other foreign prisoners at the Neuengamme concentration camp. The trials were later extended to include Jewish children. Twenty Jewish children—ten boys and ten girls, aged between 5 and 12,were selected at Auschwitz by Josef Mengele and sent to Neuengamme. According to reports, Mengele lured the children with the deceptive promise, “Who wants to go and see their mother?”

The children were escorted by four female prisoners: two Polish nurses, a Hungarian pharmacist, and a Polish-Jewish doctor named Paula Trocki. The three non-medical women were executed upon arrival at Neuengamme. Dr. Trocki survived the war and later testified in Jerusalem:

“The transport was accompanied by an SS guard. There were 20 children, one female medical doctor, three nurses. The transport was in a separate carriage that was coupled on a normal train. Presented in this manner it appeared to be an ordinary carriage. We had to take off the stars of David lest we attract any attention. To prevent people from approaching us they said it was a transport of people suffering from typhoid fever… The food was excellent; on that journey we were given chocolate and milk. After a two-day trip we arrived at Neuengamme at ten o’clock at night.”

— Paula Trocki

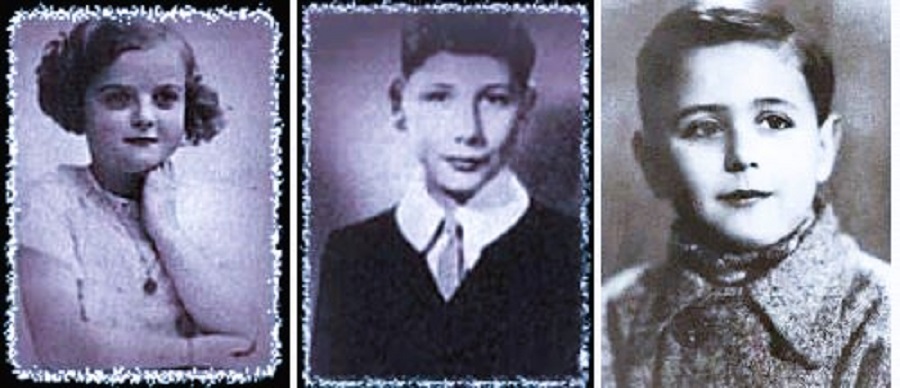

At Neuengamme, the children were injected with live tuberculosis bacilli and soon became ill. Heissmeyer then surgically removed their axillary lymph nodes for study, sending the samples to Dr. Hans Klein at the Hohenlychen Hospital. Photographs were taken of the children, each holding up an arm to display the surgical incisions. Klein was never prosecuted for his role.

As the Western Front collapsed and British forces neared Hamburg, the Nazis sought to eliminate all evidence of their crimes. Orders from Berlin called for the execution of the children and other witnesses involved in the experiments.

Between April 14 and 17, 1945, the SS began evacuating several satellite camps of Neuengamme located in Hamburg, including Dessauer Ufer, Blohm & Voss, Spaldingstraße, and Bullenhuser Damm. The Bullenhuser Damm camp, situated in a former adult education center that had originally housed thirty classrooms (see title image), was converted into a concentration camp sub-site in the autumn of 1944. This transformation followed the destruction of the Rothenburgsort district during a bombing raid on July 27–28, 1943, which had damaged the school building.

In December 1944, prisoners—originating from Poland, Denmark, France, and the Soviet Union—were brought to Bullenhuser Damm. They were forced to clear rubble and manufacture new building stones from the debris. According to a later report by SS doctor Alfred Trzebinski, there were 592 prisoners at the camp by the end of March 1945. Beginning on April 14, the SS started clearing the camp, leaving behind only two SS guards: Ewald Jauch and Johann Frahm. The remaining prisoners were transferred to the former Sandbostel prisoner-of-war camp near Bremervörde, which had been repurposed as a transit camp.

On April 19, 1945, British troops reached the Elbe River. That same day, Neuengamme commandant Max Pauly ordered the main camp to be evacuated. Scandinavian prisoners were transported to Denmark aboard Red Cross buses. Between April 20 and 26, the remaining 900 prisoners were sent to Lübeck, where they were forced onto the former luxury liner Cap Arcona and the cargo ships Thielbek and Athen. Given the high likelihood that these ships would be targeted by Allied bombers or submarines, this was effectively a death sentence. On May 3, 1945, the ships were bombed in the Bay of Lübeck by the Royal Air Force, killing around 7,000 people.

A residual task force of 600–700 SS men and prisoners remained at Neuengamme to destroy evidence of the crimes committed there. This included burning documents, dismantling execution facilities such as the gallows and beating rack, and cleaning up the camp. The last prisoners and SS personnel fled just before British troops arrived on May 2, 1945. Over its seven years of operation, at least 42,900 people perished at Neuengamme and its satellite camps.

On the morning of April 20, Schutzhaftlagerführer (Protective Custody Camp Leader) and SS-Obersturmführer Anton Thumann—previously stationed at Dachau, Gross-Rosen, and Majdanek—approached Dr. Trzebinski. According to Trzebinski’s later account, Thumann informed him:

“… I have something to tell you that is not exactly pleasant. Pauly wishes to let you know that an execution order has been issued by Berlin for the caretakers and the children, and that you are requested to kill the children using gas or poison.”

At this point, Heissmeyer had not returned to Neuengamme in over six weeks. Trzebinski claimed that he initially refused the order, but was later summoned by Pauly, who reiterated that the command had come from Berlin and insisted it was Trzebinski’s responsibility to carry it out.

During the Curiohaus trials in April 1946, Pauly testified that the execution order had been delivered via telegraph or radio. When the prosecution questioned whether such an order would have been directed to a doctor, Pauly responded:

“In my opinion, this is not impossible, since the whole matter was a medical one. Trzebinski was always in the company of Professor Heissmeyer.”

Victims

The Children of Bullenhuser Damm

Italy

Sergio De Simone (b. November 29, 1937 – d. April 20, 1945), age 7, from Naples. Arrested in Fiume and deported to Auschwitz with his mother, Gisella Perlow, who survived. Prisoner no. 179694.

Poland

Marek James, age 6, from Radom; prisoner no. B 1159.

H. Wassermann, age 8. Commemorated with Wassermann Park in Hamburg-Burgwedel.

Roman Witonski, age 6, from Radom; prisoner no. A-15160.

Eleonora Witonska, age 5, from Radom; prisoner no. A-15159. Deported with brother Roman and their mother, Rucza, from the Radom ghetto. Their father, pediatrician Seweryn Witonski, was executed in Szydłowiec. Rucza survived and later remarried.

Roman Zeller, age 12. Roman-Zeller-Platz in Hamburg-Schelsen is named in his memory.

Riwka Herszberg, age 7, from Zduńska Wola. Her mother, Mania, survived.

Mania Altmann, age 5, from Radom.

Sara Goldinger, age 11.

Lelka Birnbaum, age 12.

Ruchla Zylberberg, age 8, from Zawichost. Her mother and sister were murdered at Auschwitz. Her father, Nison Zylberberg, survived in the Soviet Union and later emigrated to the U.S.

Eduard Reichenbaum, age 10, from Katowice. His brother Itzhak survived and emigrated to Haifa.

Blumel Mekler, age 11, from Sandomierz. Her sister Shifra survived after being hidden by a Polish family, later settling in Tel Aviv.

Marek Steinbaum, age 10, from Radom. His sister Lola survived and moved to San Francisco.

Lea Klygermann, age 12; prisoner no. A-16959.

The Netherlands

Eduard (Edo) Hornemann, age 12 (b. January 1, 1933), from Eindhoven. His parents worked at the Philips factory; both died during the Holocaust.

Alexander Hornemann, age 8 (b. May 31, 1936), brother of Eduard.

France

Georges André Kohn, age 12 (b. April 23, 1932), from Paris.

Jacqueline Morgenstern, age 12 (b. May 26, 1932), from Paris. Her cousin, Henry Morgenstern, survived and has visited the memorial.

Slovakia

Walter Jungleib, age 12. Identified in 2015 through a Yad Vashem inquiry. His sister, Grete Hamburg of Hlohovec, Slovakia, confirmed his identity and survival of their family.

Caretakers

The children were accompanied by four adult male prisoners:

A French doctor

A chemist

Two Dutch prisoners

These men had been imprisoned for their anti-Nazi activities and were murdered alongside the children in order to erase all evidence of the medical experiments.

After the war, life in Hamburg resumed as though the murders at Bullenhuser Damm had never occurred. The former school building returned to its original function, once again filled with the sounds of children—yet no mention was made of the atrocities that had taken place in its basement. Students were never told what had happened within those walls. No efforts were made to contact or console the parents and siblings of the murdered children. For years, remembrance was left to a handful of former Neuengamme prisoners, who quietly returned each year, bringing flowers in honor of the twenty Jewish children whose lives were stolen there.

Two of the individuals directly responsible for the suffering and murder of the children—Kurt Heissmeyer and Arnold Strippel—initially evaded justice but were later apprehended. Strippel had previously served at several concentration camps, including Buchenwald, before being assigned to Neuengamme. In 1948, he was recognized on a street in Frankfurt by a former Buchenwald prisoner. He was subsequently tried for the murder of 21 Jewish inmates, carried out on November 9, 1939, as retaliation for Georg Elser’s failed assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich. In 1949, a Frankfurt court convicted Strippel and sentenced him to 21 life terms. The German justice system failed utterly in the case of Arnold Strippel, the main perpetrator. Despite overwhelming evidence of his involvement in the suffering and murder of innocent children, bureaucratic loopholes, legal technicalities, and a lack of political will allowed him to escape true accountability.

In the fall of 1948, Arnold Strippel voluntarily surrendered to U.S. occupation authorities at the Dachau internment camp. He was released shortly after, having presented what appeared to be valid documentation. However, in December of the same year, a former Buchenwald prisoner recognized Strippel on the street and alerted the authorities. In 1949, a West German court convicted him of 21 counts of murder, inflicting grievous bodily harm, and failing in his duty of care. He was sentenced to 21 life terms plus an additional 10 years.

In 1965, while still imprisoned, Strippel came under investigation for his role in supervising the murders of 20 Jewish children at Bullenhuser Damm—executed to conceal their use as human test subjects. However, the case was dropped after the prosecutor concluded there was insufficient evidence to prove that Strippel had acted with “base motives,” a requirement for a murder conviction under German law. Prosecution for manslaughter was also ruled out, as the statute of limitations had expired. The prosecutor likewise declined to press charges over Strippel’s supervision of the execution of 30 Soviet POWs, arguing they had been “lawfully killed” following a trial.

In 1969, Strippel’s convictions were reduced from murder to accessory to murder, and he was released on April 21 of that year, having already served more time than the revised sentence required. The following year, his sentence was officially reduced to six years, and he received compensation of approximately 121,500 Deutsche Marks from the West German government for the 14 additional years he had “unjustly” spent in prison.

In 1979, Strippel won a defamation case against a newspaper that had accused him of murdering the Soviet POWs at Bullenhuser Damm. Yet in 1981, during the Third Majdanek Trial before the West German court in Düsseldorf (1975–1981), he was convicted on 41 counts of accessory to murder for his involvement at Buchenwald and as deputy commandant at the Majdanek concentration camp. Although sentenced to 3½ years for organizing the murder of 21 Soviet POWs, he did not serve this sentence, as the time was considered already fulfilled by his prior incarceration.

In 1983, a West German court ordered a new investigation into Strippel’s role in the Bullenhuser Damm murders. However, in 1987 the case was closed due to his declining health. With the compensation money he had received from the government, Strippel purchased a condominium on Talstraße in Frankfurt-Kalbach, where he lived until his death in 1994.

Thirty-three years after the horrific events at Bullenhuser Damm, journalist Günther Schwarberg uncovered the long-buried story. In a groundbreaking series titled “The SS Doctor and the Children,” published in Stern magazine, he brought the atrocity to public attention. Through years of painstaking research across multiple countries, Schwarberg succeeded in identifying the children and locating many of their surviving relatives, giving voices and names to those whom history had nearly forgotten.

sources

https://www.kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm.de/en/introduction/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bullenhuser_Damm#Neuengamme_experimentation

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://media.offenes-archiv.de/ss1_2_2_bio_2117.pdf

https://www.alfredlandecker.org/en/article/%C3%BCber-erinnern-die-kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm

https://www.kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm.de/

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment