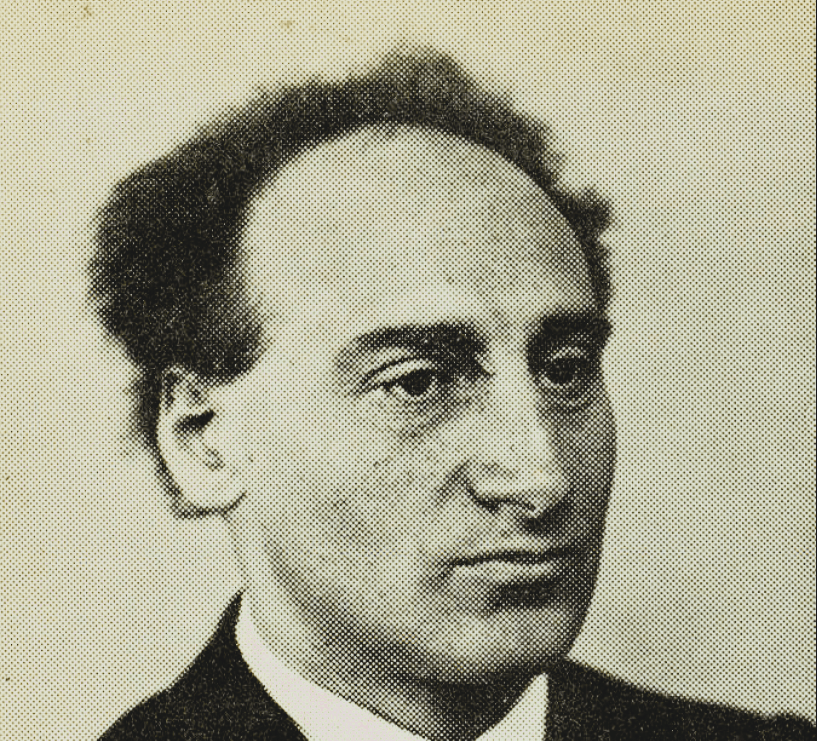

Philip Mechanicus was born, three days before Adolph Hitler, in Amsterdam on 17 April 1889 to a Jewish family. After he left school, he started to work for the social-democratic daily newspaper Het Volk in the shipping and records department. He worked his way up to become a journalist. After finishing his military service, he worked in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) for the Sumatra Post in Medan and De Locomotief in Semarang.

In 1919, he returned to The Netherlands. He joined the foreign affairs staff of the Algemeen Handelsblad in 1920. He wrote reports about the Soviet Union. It was later collected and published in book form as Van Sikkel en Hamer (From Sickle and Hammer, 1932).

After the Nazis invaded the Netherlands during World War II, Mechanicus was banned from working as a journalist. He briefly wrote under the alias Pére Celjenets. On 27 September 1942, he was arrested in the rear compartment of a tram in Amsterdam for not wearing a yellow star.

Mechanicus was transferred to the Westerbork transit camp on 7 November 1942, where he kept a diary from 28 May 28 1943 to 28 February 1944. He was deported in March 1944 to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp and sent to the death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was murdered upon arrival on 15 October 1944.

Below are excerpts from his diary:

Friday, May 28 1943

Received a new brother today, who introduced himself to all one hundred patients in the room and shook their hands. Very unusual on Westerbork, where a brother comes and goes, without further ado. Apparently a decent guy. And a professional man, it shows. Just arrived. He looks immaculately clean: snow-white nurse’s coat, which shines and shines against the filthy, filthy coats in which most of the other brothers shuffle around. Lack of cleanliness. The cleaning ladies have been in the room since yesterday instead of the cleaners who have been transported. They are led by a captain, every inch a gentleman, tall, aristocratically built, straight as an arrow, who has literary aspirations and from whose hand I have a play to read under my pillow. The cleaners used to talk, and often annoying, to the patients; Now the patients talk, and often annoying talk, to the cleaning ladies. What a delight to behold, young, nice women walking around well-dressed, one in trousers, the other in skirts. Roses in a sandy plain! They behave bravely. They are not bitter but have gallows humour. Their motto is: they won’t get us under, never! They sweep and scrub as if they had never done anything else: they carefully move every pan, every pair of shoes, every chair, every suit of clothes so as not to leave a speck of dust behind, not to leave a spot dry. Should you have seen those cleaners’ scrubs: with the French touch! How long will women maintain their sense of duty at this high level? Visited camp doctor v.d.R. Lives in a room of ± sixteen m3 with his wife, adult son and daughter. Told me he had a case of attempted suicide today: mother and two children. Timely intervention and psychological effect on the woman. High number of suicides: an average of four per week. In my barracks about six weeks ago a man of about seventy years old attempted to end his life by hanging. The eighty-year-old mother of one of my friends committed suicide these days upon arrival in Westerbork by taking poison she brought with her. Doctor v.d.R. was deeply impressed by the misery he witnesses every day, and by the weekly transports. He considered England complicit in the fate and destruction of the Jews because, although knowing what was going on, it did not intervene more forcefully to bring Germany to reason. It had to flatten Berlin and, if necessary treat it with mustard gas, then the war would be over within six weeks. If England didn’t stop the destruction of the Jews, he would wish for Germany to win the war as punishment for England. The German people had to be exterminated, and sterilized. The doctor allowed himself to be driven by his sentiment and lost sight of all objectivity, finally bursting into sobs and punching”

Friday October 15, 1943

“I cannot let go of the thought of the hostile mood of the various groups. New facts of animosity come to light every time. To Schlesinger to propose to him that he draft a proclamation, which, in the case of peace, appeals to the conscience and minds of the camp residents to maintain unity and to rise above their own petty feelings, and which is marked by many prominent Dutch and several prominent German Jews. Schlesinger is delighted and spontaneously approves the design that I present to him. He undertakes to have the proclamation printed in secret. Trottel, who accompanies me, also approves of the plan. I undertake to appoint two more Dutch Jews who are committed to the cause. Schlesinger, for his part, will appoint three German Jews.

The German authorities have rejected Dr. Spanier’s advice. That is why there will be another transport of a thousand Jews next Tuesday; unrest in the camp. I have found Dr. Willy Polak and Professor Meijers willing to work with the German Jews to maintain peace.”

Monday December 27

“Christmas passed drearily, with penal labour. One consolation was that the weather was mild.

Small conflict when picking foils. I instruct a woman and melt the grease from the condenser on the edge of the stove to make it more manageable to make. Stoker’s protest. Me: ‘You’re interfering in things that don’t concern you.’ The stoker calls in the German supervisor, my colleague. “That thing must go!” Hand movement in the direction of the capacitor. “That thing isn’t going away. You have nothing to command.’ Exchange of words, a bit of excitement. He roars—I scream. Me: ‘You Krauts always have to forbid something, otherwise you won’t be happy.’ He: ‘What, Kraut!’ His eyes bulge out of their sockets, ominous. ‘Oe ist kein gooder Kamerad. I only know Jews here.’ I had no intention of hurting him and later I went after him, grabbed his arm to throne him and settled the matter. He pulls away and walks away angrily. Later the manager at the roll call, a Dutchman: ‘You have had words. Try to settle the matter. Otherwise, I’ll have to report it. Otherwise, he’ll do it and I’ll look crazy.’ Me: ‘I’ve already tried it, but he doesn’t want to. Try to convince him that it was not meant so seriously.’ ‘Good.’ The inspector (the German boy with the steely eyes and curls under his jockey cap) appears at the roll call: ‘You said rottenmof. That’s an insult. That’s not possible. We are Jews among ourselves here.’ ‘I will put the matter straight.’ ‘Yes, but I cannot accept that here in this company. I have to report that.’ Me: ‘That’s your business, but among guys, they accept each other’s apology and hand if a word has been said in anger. That is our Dutch habit.’ He: ‘If Nussbaum wants that, I’m fine with it, but then you have to apologize publicly.’ ‘Good.’ The inspector turns away in the direction of Nussbaum. Nussbaum on stage, offering me his hand. Me: “Nussbaum, I didn’t mean anything offensive by my expression, but if you feel offended, I apologize.” Nussbaum, sentimental: “It’s beautiful like that!” The little conflict is buried in the noise of the voices of two hundred and fifty people; only those sitting nearby notice it.

I had resolved not to have any conflict. But the German command tone, their Gemass rule, gets on the nerves of the Dutch, including mine. Dutch people, who sit at the same table as Germans, can be heard shouting: ‘Those damn Germans; I can no longer see them, I can no longer hear their language.’ The same everywhere: ‘We don’t like them; they have to leave after the war. They have the faults of the Prussians and the Jews together.’ The love of humanity is put to a hard test here.”

Thursday, January 27, 1944

This morning, men and women, apparently gentlemen and ladies, looted a potato truck that stopped in front of the Central Kitchen. They boldly reached into the sacks that were lined up on the wagon, ready to be unloaded, and transferred potatoes into their sacks or bags which they had with them. Not a hint or shadow of embarrassment. Many people, formerly well-off, always go out armed with a bag, briefcase or handle bag, hoping to catch something along the way, potatoes or carrots. Some with a barrel, for collecting loose pieces of coal. The entire camp population is out for petty robbery. Many people come to the kitchen windows and quickly receive a few carrots and a few potatoes from the potato peelers, accompanied by the admonition: ‘Get out quickly, because Van Dam is always lurking; and then we go to the 51. Get away quickly! It’s dangerous!’ In the loop.

This morning, I witnessed a female member of the kitchen staff, Mrs. L., sitting on the edge of the potato spinner filling herself a bag with boiled potatoes, from which ten people could be served. The same picture in the kitchen over and over again: petty theft on a large scale. People lack but exaggerate their greed. On the one hand, the robbers are doing well, on the other hand, they are experiencing a major shortage due to too small portions. An inmate of my barracks paid eighty-five guilders for a pound of butter and exchanged another pack of cigarettes for a pound of sugar. Cigarettes are sold at one guilder each.”

Monday February 28, 1944

“Everyone robs here and no one is ashamed of it or blames the other. This morning, a few decent men and women, who were waiting for the dropouts while unloading a wagon of potatoes, emptied a bag of potatoes halfway without the intervention of the man on the wagon, also a Jew. The boundaries of what is acceptable and what is unacceptable are blurring. The practice of life here proves how easily a respected citizen, a pillar of the social order and of private property, slides down the slope into the world that thrives on plunder, when hunger begins to become acute. One can think sportily, like the rascal who steals a few apples or pears or chestnuts or carrots from a cart without betraying a criminal tendency or compromising his future. Here, one could steal three potatoes from a cart, casually, or grab them from the street to eat them, at work or in the barracks, to supplement the meager daily ration. I will do that. Like many others, I regularly walk with a few raw potatoes in the pockets of my overalls or nibble on a winter carrot. Everyone who has teeth chews on a winter carrot, starting with the children, who have strong enough teeth to bite. The whole camp is scrambling carrots; the whole camp is eating potatoes. Can I do more? Good housefathers and neat housemothers steal bags full of carrots or potatoes, from which they make steaming meals to feed their offspring, who are constantly washing and not getting enough. Early in the morning, when supervision is not yet strict, they attack the kitchen, where the potatoes are waiting for the peelers. Complete burglary with robbery. They push coals back and hide them under their coat or cloaks. They rob onions from the boxes on their way from the tow truck to the kitchen or the canteen. There is robbery in small and large, and whoever starts in small inevitably ends up in large, which is then called large. Mothers are ashamed of their sons, who come home with loot and do not know whether to encourage or discourage them. To discourage means: a chronic lack; encourage: stimulating a bad element, which they could later experience when they return to normal society. The old standards of decency have faded or disappeared, in a society in which there is no personal property, in which everyone who sits at the well takes what he can get, in which everyone, or almost everyone, who lacks, or fears a shortage, of the great hope decreases without society itself opposing it or without strict action by the guardians of order, who, by the way, are guilty of the same evil. Them—first and foremost. In this respect, society is certainly rotten: the human type is no good. Everyone here is a robber on a small or large scale, without being a criminal. Anyone who succeeds in stealing a batch of potatoes also demands space on the stove to cook his batch, often at the expense of the time of those who want to warm their legitimate leftover or portion, on coals of the community, which yields to the demand. Robbery has become commonplace and is justified by the community. People glory in the loot. There is a persistent rumour that Mr Gomperts has been arrested in Amsterdam.

Sources

https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/mech011inde01_01/

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/522590/about-philip-mechanicus

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment