Among the 97 transports from Westerbork, the one on September 3, 1944, holds particular significance. It was the last major transport from the camp and included Anne Frank, whose diary would later become one of the most poignant testimonies of the Holocaust.

Westerbork: A Transit Camp of Despair

Westerbork was initially established in 1939 as a refugee camp for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in Germany. However, after the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, Westerbork was transformed into a transit camp for Jews, Roma, and other targeted groups. From July 1942 to September 1944, Westerbork served as a crucial hub in the Nazi deportation system, facilitating the transport of over 100,000 Jews to extermination camps in the East, primarily Auschwitz and Sobibor.

Life in Westerbork was a bleak existence characterized by uncertainty, fear, and oppression. The camp was run by a Jewish council under the strict supervision of the SS, with the constant threat of deportation looming over the inmates. The camp’s population was regularly reduced by transports, which were organized with ruthless efficiency. Every Tuesday, a train would leave Westerbork, carrying thousands of men, women, and children to their deaths.

The September 3, 1944 Transport: A Journey of No Return

By September 1944, the tide of World War II was turning against Nazi Germany. The Allied forces had landed in Normandy in June 1944 and were advancing through Europe. Despite this, the Nazi regime continued its relentless pursuit of the “Final Solution.” On September 3, 1944, the last major transport from Westerbork to Auschwitz departed, carrying 1,019 people.

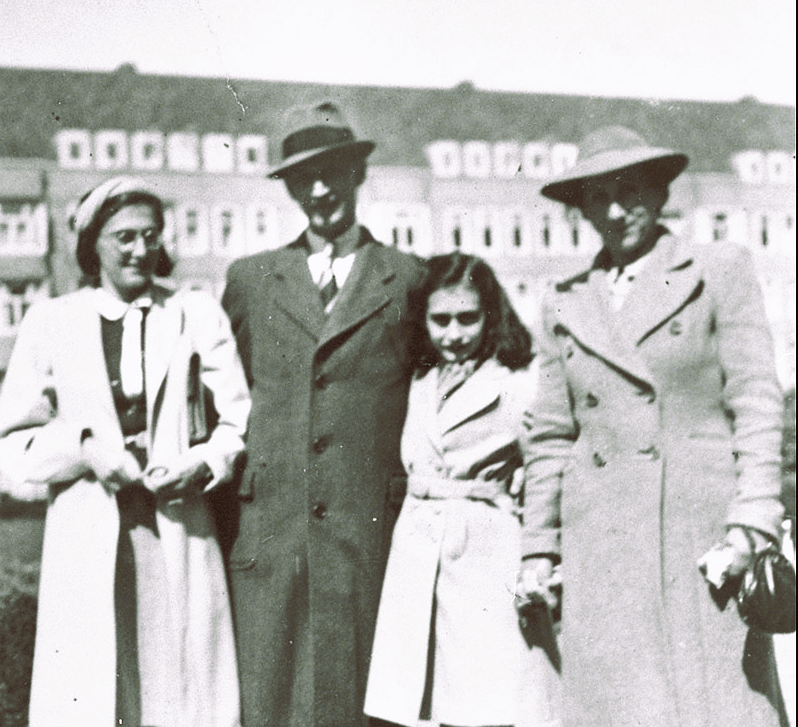

Among the deportees were Otto Frank, his daughters Anne and Margot, and several others who had been hiding in the Secret Annex in Amsterdam before being betrayed and arrested in August 1944.

The group included people from all walks of life—young and old, sick and healthy, families torn apart by the brutality of the Nazi regime. Their inclusion in this final transport marked the end of their time in Westerbork and the beginning of an even more harrowing ordeal.

The journey from Westerbork to Auschwitz took approximately three days. The deportees were crammed into cattle cars with little room to move, inadequate food and water, and no sanitary facilities. The conditions were inhumane, reflecting the Nazi regime’s utter disregard for human life. For those on board, the journey was a torturous prelude to the horrors that awaited them at their destination.

Arrival at Auschwitz:

On September 6, 1944, the train arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Upon arrival, the deportees were subjected to the infamous “selection” process conducted by SS officers, including the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele. Men were separated from women and children, and those deemed unfit for forced labor—primarily the elderly, the sick, and young children—were immediately sent to the gas chambers.

For many, including Anne Frank and her sister Margot, the journey from Westerbork marked the beginning of a new ordeal in the concentration camps. The Frank sisters were eventually transferred to Bergen-Belsen, where they died of typhus in March 1945, just weeks before the camp was liberated by British forces. Anne Frank’s father, Otto Frank, was the only member of the Frank family to survive the Holocaust. After the war, he discovered Anne’s diary, which has since become one of the most important accounts of life under Nazi persecution.

The Aftermath and Legacy of the September 3, 1944 Transport

The September 3, 1944-transport is significant not only because it was the last major transport from Westerbork but also because it symbolized the relentless efficiency of the Nazi killing machine even as the regime was on the brink of collapse. The fact that the Nazis continued to deport Jews to Auschwitz despite the advancing Allied forces underscores the deep-seated anti-Semitism and determination to carry out the “Final Solution” to its bitter end.

In the immediate aftermath of the transport, those who survived the initial selection were subjected to forced labor, starvation, disease, and the constant threat of death in Auschwitz. The camp itself was liberated by the Soviet Red Army on January 27, 1945. By that time the vast majority of those deported there, including most of those on the September 3 transport, had perished.

The legacy of the September 3 transport is inextricably linked to the broader memory of the Holocaust. Anne Frank’s diary, discovered after the war, became a powerful symbol of the human cost of hatred and intolerance. Her story, and by extension the stories of all those who were deported on that train, serves as a reminder of the atrocities committed during the Holocaust and the importance of vigilance against such horrors in the future.

However, the Frank family weren’t the only ones on that transport.

Below are just some of the statistics of the 1008 deportees.

Age Groups:

0-12: 61

13-18: 24

19-25:65

26-35: 170

36-50:278

51-65:214

66-80:122

80+: 74

59% were male, 41% were female.

The persons mentioned weren’t statistics; they were all human beings with their own stories. Here are a few of those stories.

Mirjam Lisette Katz was born in Essen, 30 April 1937. She was murdered at Auschwitz on September 6, 1944. She was 7 years old.

Heijman Karel Franken was born in The Hague on May 12, 1934. He was murdered at Auschwitz on September 6, 1944. He had reached the age of 10 years.

The Gerson Family

Ernst Gerson was born in Havixbeck, Germany on August 28, 1904. He died in Hattem on August 21, 1966 at the age of 61.

Julia Gerson-Lippers was born in Nottuln, Germany, onSeptember 1, 1911. She was murdered at Auschwitz on September 8, 1944 at 33 years of age.

Ursula Gerson was born in Münster, Germany, on June 18, 1936. She was murdered at Auschwitz on September 6, 1944, reaching the age of 8 years.

Their Story

Ernst Gerson and his family became victims of increasing aggression, intimidation, and violence in the 1930s. Ernst was arrested and imprisoned several times on unclear suspicions.

During Kristallnacht on November 9-10, 1938, Ernst’s parents’ house was targeted by anti-Jewish aggression and violence. He had already decided to go to the Netherlands in mid-May 1938, joining his wife’s sister Bertha in Zwolle. As a result, the German government revoked his German citizenship.

In 1939, his wife Sara Julia, daughter Ursula, parents-in-law Isidor and Martha Lippers, and uncle Hugo followed him to the Netherlands. They joined Bertha, who was married to a Jewish Dutchman, Siegfried de Groot, in Zwolle.

The Gerson family later moved to Hattem at the end of 1939. At that time, Ursula attended the public primary school on Dorpsweg in Hattem.

In 1939, Siegfried de Groot, the same brother-in-law from Zwolle, had already begun building a villa at Van Heemstralaan 1 in Hattem. Due to the outbreak of war, the first stone was not laid until January 1941 by both Siegfried and Bertha’s children. However, construction progressed slowly.

The Gerson family then found shelter with the Berends family near the Molecaten estate.

In September 1942, they found another hiding place on the Molecaten estate, provided by Baron W. van Heeckeren van Molecaten. Several Jews were hiding in various places on this estate.

Ernst’s parents-in-law, Isidor and Martha Lippers-Stehberg, and Uncle Hugo also found refuge in this shelter.

In the general police gazette of September 17, 1942, the mayor of Hattem already called for the arrest, tracking, and apprehension of the Gerson family. It was mentioned that they had left their place of residence without the required permits. Again, on February 25, 1943, the arrest of all members of the Gerson and Lippers families was requested.

At the beginning of September 1944, the Gerson family, along with the 14-year-old Jewish boy Georg Cohn, who was also in hiding with them, were betrayed and transported to Auschwitz via Westerbork on September 3—coincidentally, on the same train as Anne Frank.

Sara Julia Gerson-Lippers, daughter Ursula, sister Bertha, brother-in-law Siegfried, their children, her parents, uncle Hugo, and Georg Cohn did not survive the war.

Ernst’s parents and his brother also did not survive the war in Germany and were murdered in the extermination camps.

Miraculously, Ernst Gerson himself survived the war after enduring several concentration camps. He returned to Hattem after the war and resumed working in the textile trade.

Sources

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/466175/ernst-gerson

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to tzipporah batami Cancel reply