Henriëtte Pimentel (1876–1943) was the director of the daycare center on Plantage Middenlaan. With a small group of allies, she smuggled approximately 600 Jewish children from the center to safe hiding places. On Tuesday, April 19,2022 the Henriëtte Pimentel Bridge was unveiled. The beautiful bridge over the Mauritskade leading to the Tropenmuseum will officially be named after her.

Henriëtte Pimentel became a heroine during World War II. At great personal risk, she helped save hundreds of Jewish children.

Jewish Family

Pimentel came from a large Jewish family. She grew up in the former Jewish quarter between the Amstel River, Sarphatistraat, and Plantage Middenlaan. Her father died young but left her mother financially secure.

A Heart for Children

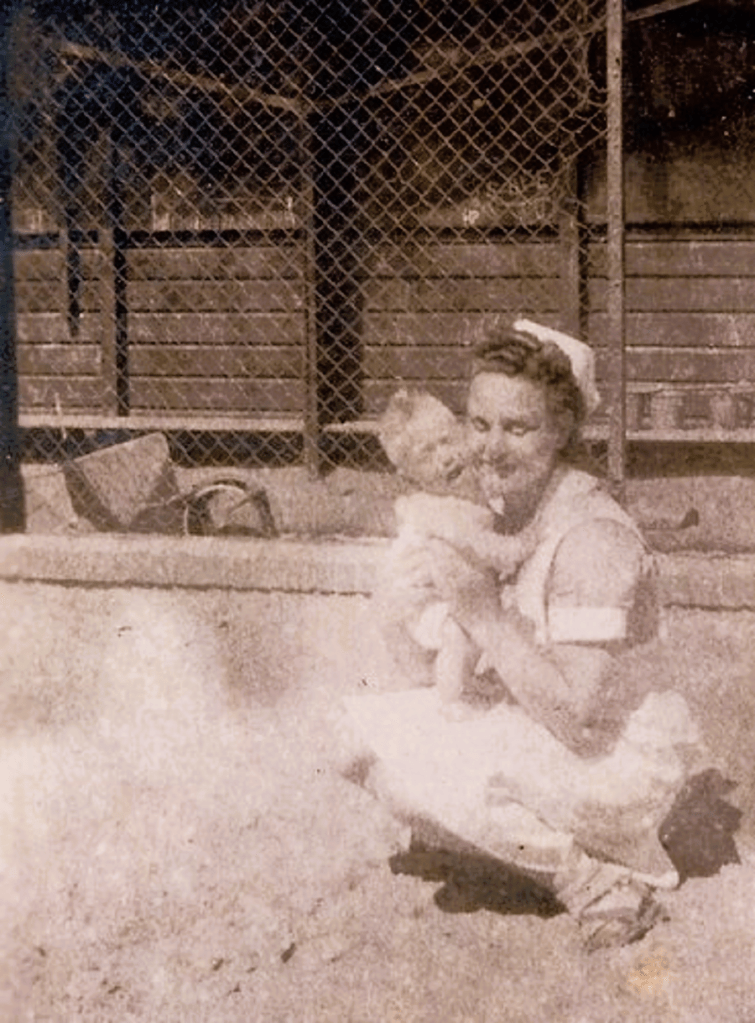

Henriëtte Pimentel had a big heart for children. She worked extensively with them and immersed herself in modern educational methods. In 1926, she became the director of the Vereeniging Zuigelingen-Inrichting en Kinderhuis (“Association for Infant Care and Children’s Home”), founded in 1906 by Jewish philanthropists, located at Plantage Middenlaan 31. Children of “all denominations” were welcome at this modern daycare center, which featured a beautiful playground and cheerfully painted classrooms.

Gathering

In 1942, the Hollandsche Schouwburg (Holland Theatre), located across from the daycare center, was seized by the German occupiers. It became the assembly point for tens of thousands of Jews captured in Amsterdam and surrounding areas. After being held there for several days, they were usually transported by train to Westerbork and then sent on to an extermination camp.

The theater was, of course, not suitable for accommodating hundreds of adults and their children. The building became overcrowded, and there were also insufficient sanitary facilities. For this reason, the Germans seized Pimentel’s daycare center directly across the street. There, dozens of children under the age of 12 stayed temporarily, waiting to be transported with their parents.

It turned out to be possible to smuggle children from the daycare center to safe hiding places. However, this required the parents’ consent. This was an extremely painful, difficult, and bitter decision for the parents. They had to give up their child while their own fate—and that of their child(ren)—remained uncertain. Additionally, the children’s names had to be erased from the German records to avoid them being listed as “missing,” which could have had life-threatening consequences. The smuggling of children was a complex and dangerous operation. The smuggling was carried out in various ways. Sometimes, for example, a childcare worker would take a child to a helper near Artis zoo around the corner. The helper would then escort the child to a safe hiding place.

In some cases, children could walk alongside the trams that moved slowly down Plantage Middenlaan. The tram served as a screen behind which the children could hide, keeping them out of sight of the Germans stationed across the street at the Schouwburg.

Children were also smuggled out through the garden at the back of the daycare center. Henriëtte Pimentel collaborated on these efforts with figures such as Wouter Süskind, Johan van Hulst, and Felix Halverstad.

The deportations from Amsterdam began in July 1942. On July 23, 1943, a raid van pulled up in front of the daycare center. At that moment, 99 percent of the staff and children were arrested. Two people managed to hide, but 37 adults and 70 children were taken away, including Henriëtte Pimentel.

They were first brought to Polderweg, then to Muiderpoort station, and finally to Westerbork. On September 14, 1943, Henriëtte Pimentel arrived in Auschwitz. She was gassed almost immediately. On September 29, 1943, Amsterdam was declared “Judenrein” (cleansed of Jews) by the Germans. According to them, the largest crime in the city’s history was complete. Of the 80,000 Jewish residents of Amsterdam, nearly 60,000 were murdered. As a result, the city of Amsterdam transformed from the beloved Mokum (a Yiddish term for “safe haven”) into a place of enduring guilt.

Testimonies

Sieny Kattenburg,childcare worker

“Director Pimentel selected a few childcare workers, including me, to help with the smuggling plan. I did it because she asked me to. Everyone had a lot of respect for her. She was very caring. For example, she insisted that my fiancé, Harry Cohen, who worked for the Jewish Council, and I get married quickly. That way, we could at least go into hiding together as a married couple.”

Levi Hagenaar

“One day, my little sister and I were summoned by the director. She said, “You will be picked up tomorrow, the day after, or the day after that. First one of you, then the other. Say your goodbyes now, because you won’t see each other for the time being.” My little sister was taken first.

It wasn’t until a week later that it was my turn. I had to walk into the garden and keep going, into the school. There, a man was waiting for me. He said, “Stay calm. We’re going outside now, and if anyone asks anything along the way, I’ll do the talking.”

Virrie Cohen, childcare worker

“I still remember poking holes in a box and placing a baby inside. I brought it to the Plantage Parklaan. That was where the office of the Jewish Community was located, which we used as a transit station. From there, children were picked up by resistance groups.”

Betty Oudkerk, childcare worker.

“I flirted with the German guards, all the while carrying a baby in a large bag. Just in a travel bag. That’s how I walked right out the front door of the crèche.”

Benjamin Flesschedrager

“When I was ten days old, my parents and I were betrayed while we were in hiding. My parents were deported, and I was rescued from the crèche. I was only a month old. A young student, Enny Lim, placed me in an empty garbage bin and carried me, via the neighbors and the school, to the outside.”

Max Degen

“I arrived at the crèche as a supposed orphan. The orphans were the easiest to get out because there were no parents who needed to give permission. I was an eight-month-old baby, which made it even easier. Babies couldn’t betray anyone, and there was always someone willing to take in a baby. Besides, they were easy to smuggle. You could simply put them in a suitcase. That’s how they got me out.”

Marcus Degen, as a small child, was in hiding for almost two years under the name Max Schaap with the Zaandam couple Arend and Welmoet (“Wellie”) Schaap-Vredenduin at Prinsenstraat 10. When Max was born, the deportation of Jews from Amsterdam to Poland was in full swing. Eva Degen, his Aunt, had to go to Westerbork on July 17, 1942; she was murdered on September 30 in Auschwitz. Max’s parents and older brother were murdered on April 9. 1943 in Sobibor.

sources

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri%C3%ABtte_Pimentel

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hollandsche_Schouwburg

https://www.lowellmilkencenter.org/competitions/discovery-award/entry/betty-goudsmit-oudkerk

https://www.amsterdam.nl/nieuws/achtergrond/redde-600-kinderen/

https://www.annefrank.org/nl/timeline/157/joodse-kinderen-gered-uit-de-hollandsche-schouwburg/

https://www.annefrank.org/nl/timeline/157/joodse-kinderen-gered-uit-de-hollandsche-schouwburg/

Please donate so we can continue this important work

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to dirkdeklein Cancel reply