Ravensbrück was a notorious Nazi concentration camp located in northern Germany, near the town of Fürstenberg. Established in 1939, it was unique in being primarily a camp for women, although a minor men’s camp was added later. Ravensbrück played a significant role in the Holocaust and the Nazi regime’s system of terror and repression.

Ravensbrück was opened in May 1939 and was operated by the SS. It was one of the last concentration camps to be established before World War II began. The camp’s primary function was to imprison women considered enemies of the Nazi state, including political prisoners, Jews, Romani people, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others. It also held a significant number of resistance fighters from occupied countries.

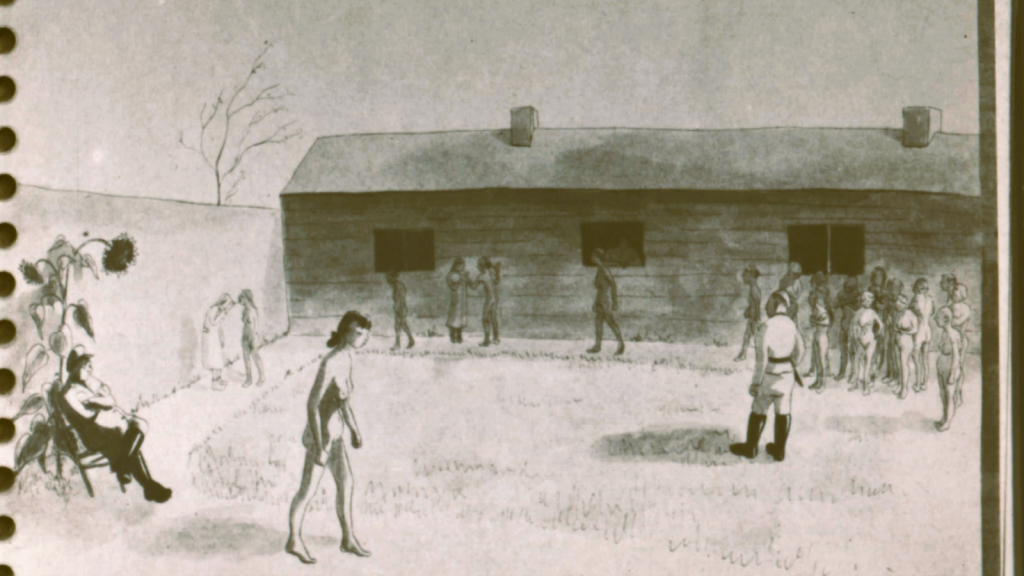

Prisoners faced brutal conditions, including overcrowded barracks, insufficient food, forced labor, and constant abuse from guards. Inmates were forced to work under inhumane conditions in various industries, including agriculture, construction, and munitions factories. Many were subjected to exhausting labor in the Siemens electrical company facilities and other enterprises.

The camp was infamous for its medical experiments on prisoners. These included tests on bone, muscle, and nerve regeneration and transplantation, often causing permanent injury, disfigurement, or death. Experiments also focused on sterilization procedures.

The camp was liberated by Soviet forces in April 1945. By that time, tens of thousands of women had suffered and died due to the horrific conditions, medical experiments, and executions.

Estimates of the number of deaths at Ravensbrück vary, but it is believed that between 30,000 to 50,000 women died out of approximately 130,000 who were imprisoned.

Women and children were usually separated early on, with any child too young to work traditionally sent to a gas chamber. But the children were here, and Ravensbruck’s gas chamber was still under construction, and all of the other camps were too full to accept prisoners from Ravensbruck. At other camps, women with children were simply shot at the camp gates. But for whatever reason, the camp commandant at Ravensbruck decided to build an enormous tent to house the Polish women and children. The tent was squalid, and disease was rampant, but at least they were alive. At first, 100 children moved into the camp. But after the rush to process new arrivals, hundreds of pregnant women were now walking around Ravensbruck. Before long, the camp had a whole new category of prisoners: newborns. One camp employee estimated that 1 in ten Polish women arriving in autumn 1944 was pregnant, meaning more than one thousand babies were due in the next year. Since Ravensbruck first opened, all pregnant prisoners received the same treatment: a forced abortion. To the astonishment of long-time prisoners, however, in the fall of 1944, Ravensbruck officials shrugged their shoulders. There were simply too many pregnancies to abort and only one camp doctor. The babies would be born, and then they would need a place to go. In October, camp officials cleared out one of the barracks and set up one of the most macabre spaces in all of Ravensbruck: the Kinderzimmer.

The conditions in the Kinderzimmer were deplorable. The infants and young children were subjected to the same harsh realities of the concentration camp environment, including malnutrition, inadequate medical care, and unsanitary conditions.

Similar to other sections of Ravensbrück, the Kinderzimmer was not exempt from the cruel medical experiments conducted by Nazi doctors. Pregnant women and their unborn children were sometimes used as subjects for these experiments, often resulting in severe harm or death.

Testimonies from survivors such as Wanda Półtawska and others who were mothers or children in the camp provide heartbreaking insights into the Kinderzimmer. These accounts describe the constant struggle for survival, the emotional torment of mothers, and the inhumane treatment of children.

Story of a Ravensbrück Hero

Born in Algeria to an Alsatian mother and a French naval officer father, Élise Rivet grew up in Lyon, France. As a young adult, she worked as a hairdresser and then joined the convent of the medical sisters of Notre Dame de Compassion in Lyon in 1912. In 1933, she became the Mother Superior of the convent and took the name Mère Marie Élisabeth de l’Eucharistie.

After France fell to Nazi Germany in World War II she, participated in the Mouvements Unis de Résistance (MUR) and l’Armée Secrète and hid their archives inside the convent. She also sheltered Jews and a British soldier, gave them identity papers, and stored guns and ammunition. On March 24, 1944, Mother Elisabeth was arrested by the Gestapo, along with her assistant Sister Mary Jésus, and taken to Prison in Lyon, where she met fellow detainee Andrée Rivière. “It was in the refectory that I saw Mother Elisabeth for the first time, whose personality and radiance came from the most depressed. She welcomed the new boarders with her calm smile which comforted us after the shock of the arrest and prison. All gathered with our Mother, as we called her, we felt a security, a moral support, a supernatural ray of hope and thought that nothing more could happen to us.”

Mother Elisabeth was deported to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp, and there, stripped of her religious garments and forced into hard labor, she ministered to her fellow prisoners and helped them turn to prayer to fight their despair.

“Sister Elisabeth was the soul of the camp,” Andrée Rivière said. “In this universe of murderous madness, she was a pole of serenity and hope, of loving presence with her companions.”

Mother Elisabeth spent a year at the camp, and just two weeks before Germany surrendered, on March 30, Good Friday, she volunteered to go to the gas chamber in the place of a woman who had children waiting for her at home, saying to her fellow prisoners as they marched: Let we go together. I will help you to die in peace.

She was fifty-five years old.

A poem about Ravensbrück

In Ravensbrück’s cold, shadowed land,

Where darkness reigned, and hope was banned,

Beneath the sky of iron gray,

The anguished souls were led astray.

The whispers of the winter’s breath,

The echoes of impending death,

In barracks bleak and void of cheer,

The cries of sorrow—always near.

A silent scream within the night,

Of courage dimmed by endless plight,

Where sisters, mothers, daughters, wives,

Fought with strength to save their lives.

In fields of pain, where time stood still,

The hearts of many broke at will,

Yet in the ash and bone’s embrace,

A flicker held a hidden grace.

For even in the darkest hour,

Amidst the grip of evil power,

A thread of light, a fleeting dream,

Through cracks of doom, began to gleam.

The hands that toiled in cruel despair,

Found ways to show they still could care,

With scraps of cloth, a doll, a song,

To prove their spirits were still strong.

Oh, Ravensbrück, a name of pain,

A testament to human stain,

But also to the strength of will,

That through the night, shines ever still.

In memory, we keep their fight,

Their voices echo through the night,

For in the telling, we ensure,

Their suffering endures no more.

Sources

https://www.holocaustliteratur.de/deutsch/Valentine-Goby-Kinderzimmer/

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1945/05/05/letter-from-paris-inside-ravensbruck

https://www.ehri-project.eu/clarin-project-voices-ravensbruck-value-multilingual-oral-history

https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/eehs-2024-0016/html?lang=en

https://www.yadvashem.org/articles/general/women-in-ravensbrueck.html

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55661782

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment