Paragraph 175 was a law which was introduced on May 15, 1871, in Germany, just after Otto von Bismarck unified Germany into a nation-state, forming the German Empire. Ironically the law remained in place until a few years after the other German re-unification. The law was abolished in 1994.

It made sexual relations between males a crime, and in early revisions, the provision also criminalized bestiality as well as forms of prostitution and underage sexual abuse. Overall, around 140,000 men were convicted under the law.

In 1935, the Nazis broadened the law so that the courts could pursue any “lewd act” whatsoever, even one involving no physical contact, such as masturbating next to each other. Convictions multiplied by a factor of ten to over 8,000 per year by 1937. Furthermore, the Gestapo could transport suspected offenders to concentration camps without any legal justification at all (even if they had been acquitted or already served their sentence in jail). Thus, over 10,000 homosexual men were forced into concentration camps, where they were identified by the pink triangle. The majority of them died there.

Between 1933 and 1945, by the USHMM’s count, an estimated 100,000 men were arrested for violating this law, and about half went to prison. It’s thought that somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 men were sent to concentration camps for reasons related to sexuality, but exactly how many died in them may never be known, between the scant documentation that survived and the sense of shame that kept many survivors silent for years after their ordeal.

When reforming the law in 1935, Nazi lawyers had a chance to extend Paragraph 175 to women. However, they chose not to do so. Nazi leaders saw lesbians as women who had a responsibility to give birth to racially pure Germans called “Aryans.” The Nazis concluded that Aryan lesbians could easily be persuaded or forced to bear children. Their beliefs drew on widespread attitudes about the differences between male and female sexuality. Furthermore, women did not typically hold leadership roles in the military, economy, or national politics. Therefore, the Nazis did not view lesbians or sexual relations between women as a direct threat to the German state.

After the annexation in 1938, Paragraph 175 also came in power in Austria. One of the people subjected to the law was Josef Kohout.

In the book “The Men With the Pink Triangle The True, Life-and-Death Story of Homosexuals in the Nazi Death Camps” by Heinz Heger. The book includes the story of Josef Kohout, Following is an excerpt of his story.

VIENNA, MARCH 1939. I was twenty-two years old, a university student preparing for an academic career, a choice that met my parents’ wishes as much as my own. Being little interested in politics, I was not a member of the Nazi student association or any of the party’s other organizations.

It wasn’t as if I had anything special against the new Germany. German was and still is my mother tongue, after all. Yet my upbringing had always been more Austrian in character. I had learned a certain tolerance from my parents, and at home, we made no distinction between people for speaking a different language from ours, practising a different religion, or having a different colour of skin. We also respected other people’s opinions, no matter how strange they might seem.

I found it far too arrogant, then, when so much started to be said at university about the German master race, our nation chosen by destiny to lead and rule all of Europe. For this reason alone, I was already not particularly keen on the new Nazi masters of Austria and their ideas.

My family was well-to-do and strictly Catholic. My father was a senior civil servant, pedantic and correct in all his actions, and always a respected model for me and my three younger sisters. He would admonish us calmly and sensibly if we made too much of a row, and he always spoke of my mother as the lady of the house. He had a deep respect for her, and as far as I can recall, he never let her birthday or saint’s day pass without bringing her flowers.

My mother, who is still alive today, has always been the very embodiment of kindness and care for us children, ever ready to help when one of us was in trouble. She could certainly scold us if need be, but she was never angry with us for long, and never resentful. She was not only a mother to us but always a good friend as well, whom we could trust with all our secrets and who always had an answer even in the most desperate situation.

Ever since I was sixteen I knew that I was more attracted to my own sex than I was to girls. At first, I didn’t think this was anything special, but when my school friends began to get romantically involved with girls, while I was still stuck on another boy, I had to give some thought to what this meant.

I was always happy enough in the company of girls and enjoyed being around them. But I came to realize early on that I valued them more as fellow students, with the same problems and concerns at school, rather than lusting after them like the other boys. The fact that I was homosexual never led me to feel the slightest repulsion for women or girls—quite the opposite. It was simply that I couldn’t get involved in a love affair with them; that was foreign to my very nature, even though I tried it a few times.

For three years I managed to keep my homoerotic feelings secret even from my mother, though I found it hard not to be able to speak about this to anyone. In the end, however, I confided in her and told her everything necessary to get it off my chest—not so much to ask her advice, however, as simply to end this burden of secrecy.

“My dear child,” she replied, “it’s your life, and you must live it. No one can slip out of one skin and into another; you have to make the best of what you are. If you think you can find happiness only with another man, that doesn’t make you in any way inferior. Just be careful to avoid bad company, and guard against blackmail, as this is a possible danger. Try to find a lasting friendship, as this will protect you from many perils. I’ve suspected it for a long time, anyway. You have no need at all to despair. Follow my advice, and remember, whatever happens, you are my son and can always come to me with your problems.”

I was very much heartened by my mother’s reasonable words. Not that I really expected anything else, as she always remained her children’s best friend.

At university, I became friendly with several students with views, or, rather, feelings, similar to my own. We formed an informal group, small at first, though after the German invasion and the “Anschluss” this was soon enlarged by students from the Reich. Naturally enough, we didn’t just help one another with our work. Couples soon formed too, and at the end of 1938, I met the great love of my life.

Fred was the son of a high Nazi official from the Reich, two years older than I, and set on completing his study of medicine at the world-famous Vienna medical school. He was forceful, but at the same time sensitive, and his masculine appearance, success in sport, and great knowledge made such an impression on me that I fell for him straight away. I must have pleased him too, I suppose, with my Viennese charm and temperament. I also had an athletic figure, which he liked. We were very happy together, and made all kinds of plans for the future, believing we would nevermore be separated.

It was on a Friday, about 1 p.m., almost a year to the day since Austria had become simply the “Ostmark,” that I heard two rings at the door. Short, but somehow commanding. When I opened I was surprised to see a man with a slouch hat and leather coat. With the curt word “Gestapo,” he handed me a card with the printed summons to appear for questioning at 2 p.m. at the Gestapo headquarters in the Hotel Metropol.

My mother and I were very upset, but I could only think it had to do with something at the university, possibly a political investigation into a student who had fallen foul of the Nazi student association.

“It can’t be anything serious,” I told my mother, “otherwise the Gestapo would have taken me off right away.”

My mother was still not satisfied and showed great concern. I, too, had a nervous feeling in my stomach, but then doesn’t anyone in a time of dictatorship if they are called in by the secret police?

I happened to glance out of the window and saw the Gestapo man a few doors farther along, standing in front of a shop. It seemed he still had his eye on our door, rather than on the items on display.

Presumably, his job was to prevent any attempt by me to escape. He was undoubtedly going to follow me to the hotel. This was extremely unpleasant to contemplate, and I could already feel the threatening danger.

My mother must have felt the same, for when I said goodbye to her she embraced me very warmly and repeated: “Be careful, child, be careful!”

Neither of us thought, however, that we would not meet again for six years, myself a human wreck, she a broken woman, tormented as to the fate of her son, and having had to face the contempt of neighbours and fellow citizens ever since it was known her son was homosexual and had been sent to a concentration camp.

My father was forced to retire on a reduced pension in December 1940. He could no longer put up with the abuse he received, and in 1942 took his own life—filled with bitterness and grief for an age he could not fit into, filled with disappointment over all those friends who either couldn’t or wouldn’t help him. He wrote a farewell letter to my mother, asking her forgiveness for having to leave her alone. My mother still has the letter today, and the last lines read, “And so I can no longer tolerate the scorn of my acquaintances and colleagues, and of our neighbours. It’s just too much for me! Please forgive me again. ‘God protect our son!’

I was taken to the police prison on Rossauerlände Street, which we Viennese know as the “Liesl,” as the street used to be called the Elisabethpromenade.

My pressing request to telephone my mother to tell her where I’d been taken was met with the words: “She’ll soon know you’re not coming home again.”

I was then examined bodily, which was very distressing, as I had to undress completely so that the policeman could make sure I was not hiding any forbidden object, even having to bend over. Then I could get dressed again, though my belt and shoelaces were taken away. I was locked in a cell designed for one person, though it already had two other occupants. My fellow prisoners were criminals, one under investigation for housebreaking, the other for swindling widows on the lookout for a new husband. They immediately wanted to know what I was in for, which I refused to tell them. I simply said that I didn’t know myself. From what they told me, they were both married and between thirty and thirty-five years old.

When they found out that I was “queer,” as one of the policemen gleefully told them, they immediately made open advances to me, which I angrily rejected. First, I was in no mood for amorous adventures, and in any case, as I told them in no uncertain terms, I wasn’t the kind of person who gave himself to anyone.

They then started to insult me and “the whole brood of queers,” who ought to be exterminated. It was an unheard-of insult that the authorities should have put a subhuman such as this in the same cell as two relatively decent people. Even if they had come into conflict with the law, they were at least normal men and not moral degenerates. They were on a quite different level from homos, who should be classed as animals. They went on with such insults for quite a while, stressing all the time how they were decent men in comparison with the filthy queers. You’d have thought from their language that it was me who had propositioned them, not the other way around.

As it happened, I found out the very first night that they had sex together, not even caring whether I saw or heard. But in their view—the view of “normal” people—this was only an emergency outlet, with nothing queer about it.

As if you could divide homosexuality into normal and abnormal. I later had the misfortune to discover that it wasn’t only these two gangsters who had that opinion, but almost all “normal” men. I still wonder today how this division between normal and abnormal is made. Is there a normal hunger and an abnormal one? A normal thirst and an abnormal one? Isn’t hunger always hunger, and thirst thirst? What a hypocritical and illogical way of thinking!

Two weeks later, my trial was already up, justice showing an unusual haste in my case. Under Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code, I was condemned by an Austrian court for homosexual behaviour, and sentenced to six months penal servitude with the added provision of one fast day a month.

Proceedings against the second accused, my friend Fred, were dropped on the grounds of “mental confusion.” No exact explanation was given as to what this involved, and it was clear enough from the judge’s face that he was less than happy with this formula. Never mind, in Hitler’s Third Reich even the judges, supposedly so independent, had to adapt to Nazi reasons of state.

Some “higher power” had put in a finger and influenced the court proceedings. Presumably, Fred’s father had used his weight as a Nazi high-up and managed to get his son out of trouble.

On the day that my six months were up, and I should have been released, I was informed that the Central Security Department had demanded that I remain in custody. I was again transferred to the “Liesl,” for transit to a concentration camp.

This news was like a blow on the head, for I knew from other prisoners who had been sent back from concentration camps for the trial that we “queers,” just like the Jews, were tortured to death in the camps, and only rarely came out alive. At that time, however, I couldn’t, or wouldn’t, believe this. I thought it was an exaggeration, designed to upset me. Unfortunately, it was only too true!”

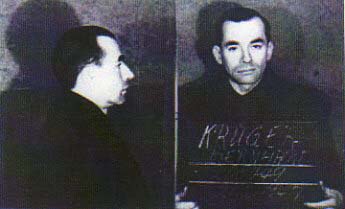

Josef Kohout was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in mid-January 1940. Four months later, he was transferred to Flossenbürg. He worked as a Kapo in forced labour in the loading commando at the train station. His position as a Kapo was unusual for a homosexual inmate. He survived, as he explained, because of his good relations with other “green” Kapos. During the death march in April 1945, Kohout succeeded in escaping near Cham.

Josef Kohout lived with his partner in Vienna until his death on March 15, 1994, three months before Paragraph 175 was abolished.

Sources:

https://www.gedenkstaette-flossenbuerg.de/en/history/prisoners/josef-kohout

https://time.com/5295476/gay-pride-pink-triangle-history

https://jewishcurrents.org/the-men-with-the-pink-triangle

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.