In the Middle Ages, animals who committed crimes were subject to the same legal proceedings as humans.

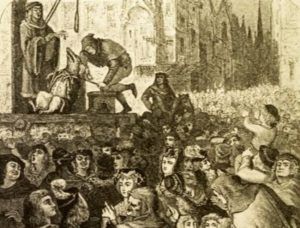

Famously, in 1457, seven pigs in Savigny, France were tried for the murder of a five-year-old boy. The proceedings were complete with a defense attorney for the pigs and a judge, who ultimately ruled that because people witnessed one of the seven pigs attack the boy, only that one would sentenced to death by hanging, and the rest would go free.

Animals, including insects, faced the possibility of criminal charges for several centuries across many parts of Europe. The earliest extant record of an animal trial is the execution of a pig in 1266 at Fontenay-aux-Roses.

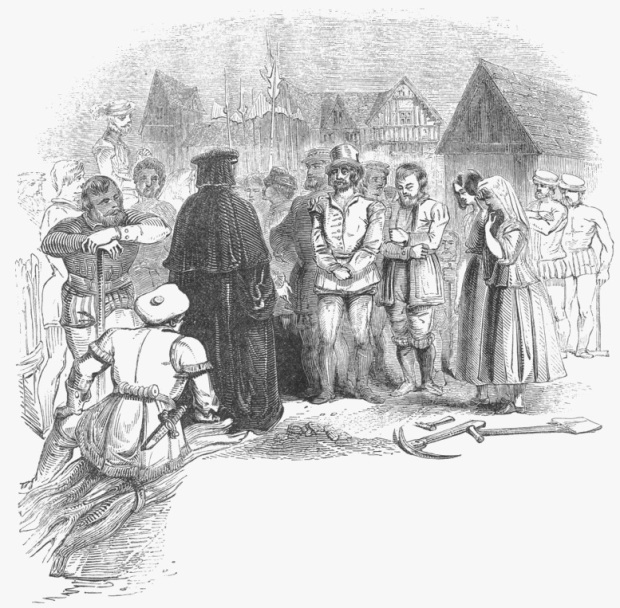

Such trials remained part of several legal systems until the 18th century. Animal defendants appeared before both church and secular courts, and the offences alleged against them ranged from murder to criminal damage. Human witnesses were often heard and in Ecclesiastical courts they were routinely provided with lawyers (this was not the case in secular courts, but for most of the period concerned, neither were human defendants). If convicted, it was usual for an animal to be executed, or exiled. However, in 1750, a female donkey was acquitted of charges of bestiality due to witnesses to the animal’s virtue and good behaviour while her human co-accused were sentenced to death.

Animals put on trial were almost invariably either domesticated ones (most often pigs, but also bulls, horses, and cows) or pests such as rats and weevils. Creatures that were suspected of being familiar spirits or complicit in acts of bestiality were also subjected to judicial punishment, such as burning at the stake, though few, if any, ever faced trial

According to Johannis Gross in Kurze Basler Chronik (1624), in 1474 a rooster was put on trial in Basel ,Switzerland for “the heinous and unnatural crime of laying an egg,” which the townspeople were concerned was spawned by Satan and contained a cockatrice.

Scholars and historians who study the middle ages have cited numerous possible explanations for why such proceedings took place. The greater mentality of medieval societies was characterized by strong superstitions and a rigid hierarchy of humanity rooted in faith a divine God. Some academics hypothesized that, because of the importance of this belief system, any event that represented a departure in the hierarchy of nature, where a God had placed humans at the top, needed to be formally addressed in order to restore proper order. Another possible explanation for the trials was that because they were so public and conspicuous, they were able to serve as warnings directed at owners whose animals were causing mischief in communities.

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.