Although the Japanese may have called it an Internment camp, make no mistake about it, Tjideng was nothing other then a concentration camp.

Batavia came under Japanese control in 1942, and part of the city, called Camp Tjideng, was used for the internment of European (often Dutch) women and children. The men and older boys were transferred to other camps, many to prisoner of war camps.

Initially Tjideng was under civilian authority, and the conditions were bearable. But when the military took over, privileges (such as being allowed to cook for themselves and the opportunity for religious services) were quickly withdrawn. Food preparation was centralised and the quality and quantity of food rapidly declined. Hunger and disease struck, and because no medicines were available, the number of fatalities increased.

The area of Camp Tjideng was over time made smaller and smaller, while it was obliged to accommodate more and more prisoners. Initially there were about 2,000 prisoners and at the end of the war there were approximately 10,500, while the territory had been reduced to a quarter of its original size. Every bit of space was used for sleeping, including the unused kitchens and waterless bathrooms.

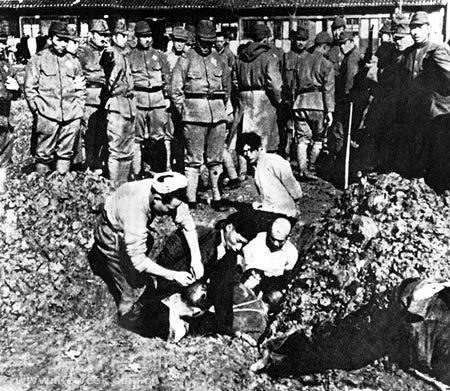

From April 1944 the camp was under the command of Captain Kenichi Sonei, who was responsible for many atrocities. After the war Sonei was arrested, and sentenced to death on September 2, 1946.

The sentence was carried out by a Dutch firing squad in December of that year, after a request for pardon to the Dutch lieutenant governor-general, Hubertus van Mook, was rejected. Van Mook’s wife had been one of Sonei’s prisoners.

UK FormerDeputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg’s mother, Hermance, was in Camp Tjideng in Batavia, with her mother and sisters.

She remembers having to bow deeply towards Japan at Tenko, “with our little fingers on the side seams of our skirt. If we did not do it properly we were beaten.” Another punishment, head shaving, was so common that the women would simply wrap a scarf round their bloodied scalp and carry on.

Worse even than these sanctions was the fear of starvation as the rations of what passed for food , tapioca gruel ,dwindled to half a cup per person a day. Desperate to keep their children alive, women would catch frogs, lizards and snails and boil them in a tin cup on the back of their irons.

The more daring risked being savagely beaten or even executed, as they crept to the fence to trade their meager possessions with local people for a banana or a couple of eggs. The internees became so obsessed with food that they would feverishly swap recipes, writing out the ingredients, discussing the method then mentally savouring the delicious dish that they would never get to eat.

Amid all this, the greatest fear for mothers of boys was that their sons would be taken away. The age at which boys were transferred to men’s camps dropped from 15 at the start of the war, to 13 then 11, until by 1944 boys of 10 were being transported. As they waited to climb on to the lorries they would cling to their mothers, not knowing whether they’d ever see them again.

The squalor from open sewers and the ever-present hunger inevitably led to disease – beriberi and dysentery were rife.Sometimes there were dozens of deaths a day in the camp.The camp was ruled by a cruel and brutal officer named  Captain Kenichi Sonei.

Captain Kenichi Sonei.

Beatings were a daily event, women would have their heads shaved for failing to bow properly, Red Cross parcels were hidden away.

Every day Sonei would order Tenko. “Tenko means roll call,” a survivor explained. “We were constantly left standing for hours in the sun during Tenko.

“On one such occasion, as we walked past the guards, my mother was smoking a cigarette, just received in a precious Red Cross parcel.The camp commandant spotted her and, furious because she had not shown him the respect he expected from the hated Dutch women, he strolled over and smacked her hard on the face. My world nearly fell apart. I pleaded with him not to hit her again and at that moment he was distracted because one of the guards drew his attention to somebody else’s misdemeanour.”

A girl had been spotted holding a little puppy. Sonei rattled out an order.

“The guard took the puppy from her and, with a wide grin on his face, put a piece of string round its neck and hanged it from the barbed wire fence.”

Such barbarous acts were committed on an almost daily basis.

By the time liberation came on 15 August 1945, the degradation of these women was complete. Like the POWs in their loin cloths, they had virtually no clothes, many wearing old tea towels for bras, and “sandals” fashioned out of strips of rubber tyres.

Like the POWs they were skeletally thin, half-blind with malnutrition and, as with the POWs, huge numbers had died.

(Emaciated inmates in the hospital of the Tjideng internment camp on Java, Indonesia in December 1945.

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.