On Good Friday, 10 April 1998, the Good Friday Agreement, also known as the Belfast Agreement, It consists of two closely related agreements,

the British-Irish Agreement and the Multi-Party Agreement. It led to the establishment of a system of devolved government in Northern Ireland and the creation of many new institutions such as the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive, the North South Ministerial Council and the British-Irish Council. The Good Friday Agreement was approved by referendums held in both Ireland and Northern Ireland on 22 May 1998.

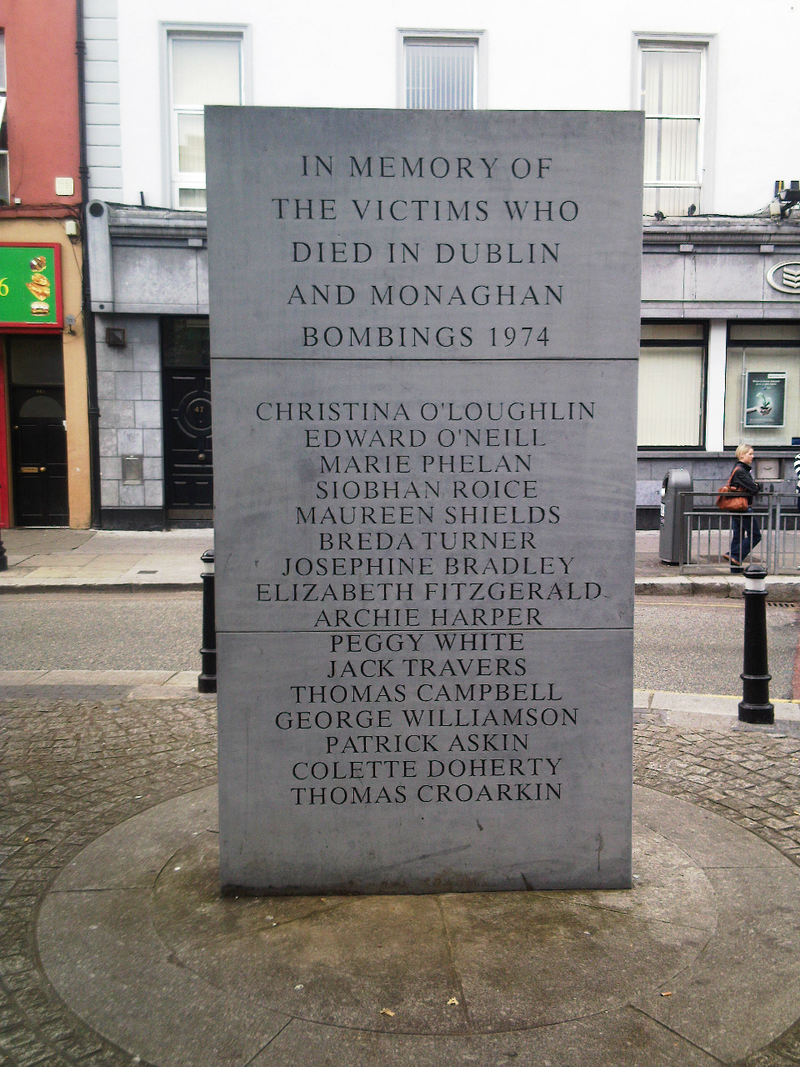

Northern Ireland was created in 1921 and remained part of the UK when the rest of Ireland became an independent state. This created a split in the population between unionists, who wish to see Northern Ireland stay within the UK, and nationalists, who want it to become part of the Republic of Ireland. From the late 1960s, armed groups from both sides, such as the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), and other smaller paramilitary groups, carried out bombings and shootings, and British troops were sent to Northern Ireland. The Troubles lasted almost 30 years and cost the lives of more than 3,500 people. The Good Friday put an end to the violence, creating a lasting but fragile peace for the last 25 years.

Below are just some impressions of the decades of the troubles in Northern Ireland

As buildings burn, British Army troops patrol the streets after being deployed to end the Battle of the Bogside in Derry on August 15, 1969.

The conflict, beginning on August 12 and ending on August 15 with the arrival of the army, involved police officers from the loyalist Royal Ulster Constabulary and the nationalist citizens of the Bogside neighborhood and was one of the first major incidents of the Troubles.

A British soldier trains his rifle on a suspect in the Republican Ballymurphy estate in West Belfast on April 12, 1972.

An IRA member squats on patrol in West Belfast as women and children approach. 1987.

An inspector of the loyalist Royal Ulster Constabulary carries an injured women from a shopping arcade in Donegall Street, Belfast, after an IRA bomb went off there. March 20, 1972.

Masked men fire volleys of rifle shots in 1981 over the coffin of hunger-striker Bobby Sands.

A protestant boy plays football on a street in the sectarian divide of North Belfast where a British soldier is on patrol. January 21, 1972.

Women of the IRA pose with M16 rifles during a training and propaganda exercise in Northern Ireland on February 12, 1977.

August 1969: soldiers and civilians in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

The Catholic priest Edward Daly waving a blood-stained white handkerchief while trying to escort the mortally wounded Jackie Duddy to safety during Bloody Sunday, or the Bogside Massacre. A massacre on 30 January 1972 when British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest march in the Bogside area of Derry. Fourteen people died: thirteen were killed outright, while the death of another man four months later was attributed to his injuries.

British soldiers killed 14 civilians.

An ambulance collects victims of British paratroopers at dusk on Rossville St, Derry, on Bloody Sunday.

The deadliest single incident of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, happened 4 months after the Good Friday agreement. In Omagh, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, on August 15, 1998, in which a bomb concealed in a car exploded, killing 29 people and injuring more than 200 others. The Omagh bombing, carried out by members of the Real Irish Republican Army (Real IRA, or New IRA).

The peace has been consistent , but fragile ever since.

sources

https://www.britannica.com/event/Omagh-bombing

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-61968177

You must be logged in to post a comment.