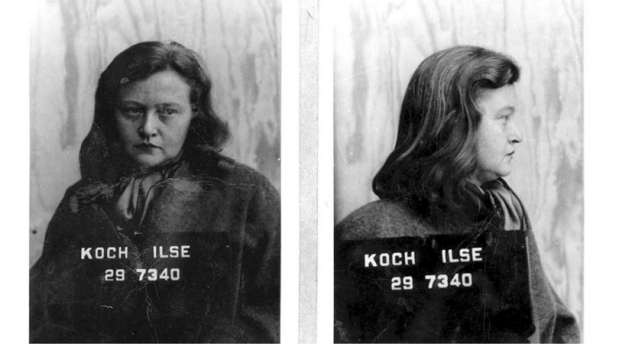

On this day in 1951, Ilse Koch, wife of the commandant of the Buchenwald concentration camp, was sentenced to life imprisonment in a court in West Germany. Ilse Koch was nicknamed the “Witch of Buchenwald” for her extraordinary sadism.

Koch was born in Dresden, Germany, the daughter of a factory foreman. She was known as a polite and happy child in her elementary school. At the age of 15, she entered an accountancy school. Later, she went to work as a bookkeeping clerk. At the time the economy of Germany had not yet recovered from Germany’s defeat in World War I. In 1932, she became a member of the rising Nazi Party.

On May 29, 1937, she married Karl Otto Koch, a colonel in the SS who was commander of the Sachsenhausen camp. In the summer of 1937 he was transferred to Buchenwald, then a new concentration camp near Weimar. There Koch acquired her reputation as a sadist and nymphomaniac, beating prisoners with her riding crop and forcing them to perform physically exhausting activities for her own amusement. Koch and her husband enjoyed a lavish lifestyle in an elegant house on Buchenwald’s grounds, and he had a large horseback-riding arena built especially for her. Although the inmates were forced into starvation, the Kochs had all the food and alcohol they wanted, and they are alleged to have held orgies at their house for their SS staff.

In the summer of 1937 he was transferred to Buchenwald, then a new concentration camp near Weimar. There Koch acquired her reputation as a sadist and nymphomaniac, beating prisoners with her riding crop and forcing them to perform physically exhausting activities for her own amusement. Koch and her husband enjoyed a lavish lifestyle in an elegant house on Buchenwald’s grounds, and he had a large horseback-riding arena built especially for her. Although the inmates were forced into starvation, the Kochs had all the food and alcohol they wanted, and they are alleged to have held orgies at their house for their SS staff.

The iron gate that led into the camp read Jedem das Seine, which literally meant “to each his own,” but was intended as a message to the prisoners: “Everyone gets what he deserves.”

Koch had three children with her husband—son Artwin and daughters Gisele and Gudrun; Gudrun died in infancy.

Ilse Koch jumped at the opportunity to become involved in her husband’s work, and over the next few years gained a reputation for being one of the most feared Nazis at Buchenwald. Her first order of business had been to use money stolen from prisoners to construct a $62,500 (around $1 million in today’s money) indoor sports arena where she could ride her horses.

Koch would often take this pastime outside the arena and into the camp itself, where she would taunt prisoners until they looked at her — at which point she would whip them. Survivors of the camp recalled later, during her trial for war crimes, that she always seemed particularly excited about sending children to the gas chamber.

Her other hobby, which would later become a major point of contention during the Nuremberg Trials, was her collection of lampshades, book covers, and gloves, said to have been made from human skin.

Witnesses later recalled that Ilse Koch often took her horseback rides through the camps to scout out prisoners who had distinctive tattoos. The prisoner would be stripped of his or her skin before being incinerated, and Koch allegedly kept the skin on display in her home with the Commandant. These artifacts were recovered after the camp’s liberation and served as key evidence during her trial.

In 1941 Karl Otto Koch was transferred to Lublin, where he helped establish the Majdanek concentration and extermination camp. Koch had three children with her husband—son Artwin and daughters Gisele and Gudrun; Gudrun died in infancy.Ilse Koch remained at Buchenwald until 24 August 1943, when she and her husband were arrested on the orders of Josias von Waldeck-Pyrmont, SS and Police Leader for Weimar,

who had supervisory authority over Buchenwald. The charges against the Kochs comprised private enrichment, embezzlement, and the murder of prisoners to prevent them from giving testimony.

Ilse Koch was imprisoned until 1944 when she was acquitted for lack of evidence. Her husband was found guilty and sentenced to death by an SS court in Munich, and was executed by firing squad on 5 April 1945 in the court of the camp he once commanded. She went to live with her surviving family in the town of Ludwigsburg, where she was arrested by U.S. authorities on 30 June 1945.

After World War II, Koch and her children went to live in Ludwigsburg, a suburb of Stuttgart, but the Allies arrested and jailed her to await trial. In 1947 a sensational Allied military tribunal held at the former Dachau concentration camp tried her and 30 others connected with Buchenwald. She was charged with several crimes, including abusing prisoners and ordering those with “interesting” tattoos to be killed and their skin turned into artifacts such as lampshades, book covers, gloves, and so on. Despite the testimony of former prisoners who were forced to make such grisly objects, prosecutors could not conclusively prove her involvement in committing such crimes. Koch announced in the courtroom that she was eight months pregnant but on 19 August 1947, she was sentenced to life imprisonment for “violation of the laws and customs of war”At the Landsberg Prison in October 1947, she gave birth to a son, Uwe, likely fathered by a fellow prisoner, Fritz Schäffer.

On 8 June 1948 after she had served two years of her sentence, Gen. Lucius D. Clay, the interim military governor of the American Zone in Germany, reduced the judgment to four years imprisonment on the grounds “there was no convincing evidence that she had selected inmates for extermination in order to secure tattooed skins, or that she possessed any articles made of human skin”.

News of the reduced sentence did not become public until 16 September 1948. Despite the ensuing uproar, Clay stood firm. Jean Edward Smith in his biography, Lucius D. Clay: An American Life, reported that the general maintained the leather lamp shades were really made out of goat skin. The book quotes a statement made by Clay years later:

There was absolutely no evidence in the trial transcript, other than she was a rather loathsome creature, that would support the death sentence. I suppose I received more abuse for that than for anything else I did in Germany. Some reporter had called her the “Bitch of Buchenwald”, had written that she had lamp shades made of human skin in her house. And that was introduced in court, where it was absolutely proven that the lampshades were made out of goatskin. In addition to that, her crimes were primarily against the German people; they were not war crimes against American or Allied prisoners … Later she was tried by a German court for her crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment. But they had clear jurisdiction. We did not.

Under the pressure of public opinion Koch was re-arrested in 1949 and tried before a West German court. The hearing opened on 27 November 1950 before the District Court at Augsburg and lasted seven weeks, during which 250 witnesses were heard, including 50 for the defense. Koch collapsed and had to be carried from the court in late December 1950,and again on 11 January 1951.At least four separate witnesses for the prosecution testified that they had seen Koch choose tattooed prisoners, who were then killed, or had seen or been involved in the process of making human-skin lampshades from tattooed skin.

However, this charge was dropped by the prosecution when they could not prove lampshades or any other items were actually made from human skin.

On 15 January 1951, the Court pronounced its verdict, in a 111-page-long decision, for which Koch was not present in court. It was concluded that the previous trials in 1944 and 1947 were not a bar to proceedings under the principle of ne bis in idem, as at the 1944 trial Koch had only been charged with receiving, while in 1947 she had been accused of crimes against foreigners after 1 September 1939, and not with crimes against humanity of which Germans and Austrians had been defendants both before and after that date. She was convicted of charges of incitement to murder, incitement to attempted murder and incitement to the crime of committing grievous bodily harm, and on 15 January 1951 was sentenced to life imprisonment and permanent forfeiture of civil rights.

Koch appealed to have the judgment quashed, but the appeal was dismissed on 22 April 1952 by the Federal Court of Justice. She later made several petitions for a pardon, all of which were rejected by the Bavarian Ministry of Justice. Koch protested her life sentence, to no avail, to the International Human Rights Commission.

While in prison, her son Uwe, who had been conceived during her imprisonment at Dachau, discovered that she was his mother. He came to visit her in prison often over the next several years at Aichach, the prison where she was serving her life sentence.

On September 1, 1967, Ilse Koch committed suicide in prison,by hanging herself with a bedsheet. The next day, Uwe arrived for their visit and was shocked to find that she had died. She was buried in an unmarked, untended grave at the prison’s cemetery.

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.