When we think of the World War II war crime tribunal we usually think about the Nuremberg Trials, however, there were several trials for the Nazis who weren’t the only ones who had committed war crimes. The Japanese Imperial Army was also guilty of atrocities, and some of them were more brutal and evil than the crimes committed by the Nazis.

The Tokyo trials known as The International Military Tribunal for the Far East, began on May 3, 1946 and lasted two and a half years. Three broad categories of war crimes were established. Class A charges, alleging “crimes against peace,” were brought against the Japan’s top leaders who had planned and directed the war. Class B and C charges, which were leveled at the Japanese of any rank, covered “conventional war crimes” and “crimes against humanity.” Former U.S. assistant attorney general, Joseph Keenan, served as the chief prosecutor. He was a Roosevelt New Dealer and had once personally prosecuted such infamous American gangsters as “Machine Gun Kelley.”

Sir William Webb of Australia served as the tribunal’s president. Eleven judges representing various countries presided. On November 4, 1948, Webb announced that all defendants had been found guilty. Seven sentenced to death (including the most infamous, former Prime Minister Hideki Tojo); sixteen received life terms (though many paroled in the 1950s), and two given lesser terms. Two had died during the trials, and one was found insane. Hundreds of subsequent war crimes trials were held in other countries in Asia into the 1950s. These Tokyo trials, while important, have often remained in the shadow of the more publicized Nuremberg war crimes trials in Europe.

General Douglas MacArthur was pleased with the Tokyo trials and stated, “No human decision is infallible but I can conceive of no judicial process where greater safeguard was made to evolve justice.…no mortal agency in the present imperfect evolution of civilized society seems more entitled to confidence in the integrity of its solemn pronouncements. If we cannot trust such processes and such men we can trust nothing.”

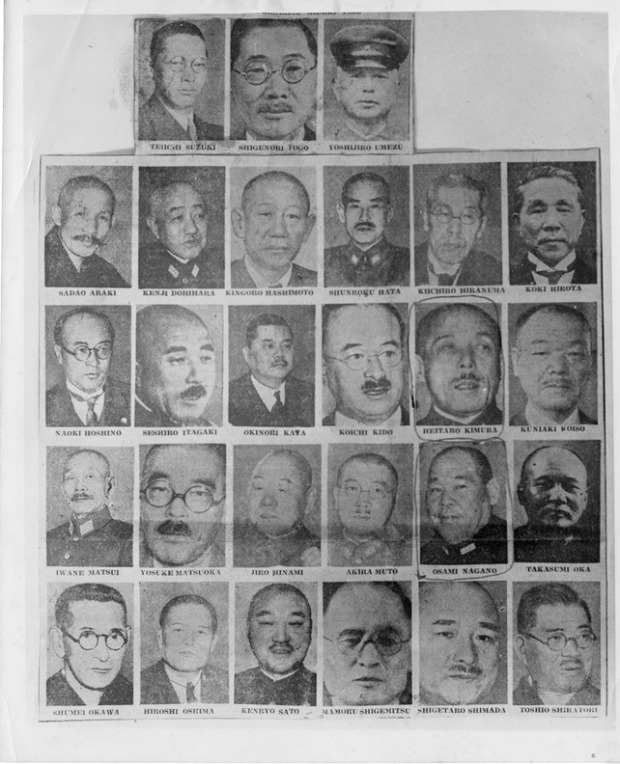

The U.S. and its allies established an International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMFTE) to prosecute Japanese military and government leaders. Twenty-eight high-ranking Japanese political and military leaders, often referred to as the “Big Fish”, along with others were indicted on 55 counts in the most publicized Tokyo trial. The accused group included former prime ministers, foreign ministers, economic and financial leaders, ambassadors, war ministers, navy ministers, and senior military officers. General Douglas MacArthur decided, with President Truman’s concurrence, not to place Emporer Hirohito or any member of the royal family on trial. He was seen by the victors as a much-needed leader and symbol for the new, peaceful and democratic Japan to arise from the ashes of WW II. The U.S. was entering a new Cold War era and needed a militarily purged, newly reborn Japan as an ally with Hirohito as its unifying symbol.

As many as 50 suspects, such as Nobusuke Kishi, who later became Prime Minister, and Yoshisuke Aikawa, head of Nissan, were charged but released in 1947 and 1948. Shiro Ishii received immunity in exchange for data gathered from his experiments on live prisoners. The lone dissenting judge arguing to exonerate all arrested suspects was Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal.

Following the model used at the Nuremberg Trials in Germany, the Allies established three broad categories. “Class A” charges, alleging crimes against peace, were to be brought against Japan’s top leaders who had planned and directed the war. Class B and C charges, which could be leveled at Japanese of any rank, covered conventional war crimes and crimes against humanity, respectively. Unlike the Nuremberg Trials, the charge of crimes against peace was a prerequisite to prosecution—only those individuals whose crimes included crimes against peace could be prosecuted by the Tribunal.

The indictment accused the defendants of promoting a scheme of conquest that “contemplated and carried out…murdering, maiming and ill-treating prisoners of war (and) civilian internees…forcing them to labor under inhumane conditions…plundering public and private property, wantonly destroying cities, towns and villages beyond any justification of military necessity; (perpetrating) mass murder, rape, pillage, brigandage, torture and other barbaric cruelties upon the helpless civilian population of the over-run countries.

The prosecution began opening statements on May 3, 1946, and took 192 days to present its case, finishing on January 24, 1947. It submitted its evidence in fifteen phases.

The Charter provided that evidence against the accused could include any document “without proof of its issuance or signature” as well as diaries, letters, press reports, and sworn or unsworn out-of-court statements relating to the charges.[6] Article 13 of the Charter read, in part: “The tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence…and shall admit any evidence which it deems to have probative value”.

Numerous eye-witness accounts of the Nanking Massacre were provided by Chinese civilian survivors and western nationals living in Nanking at the time. The accounts included gruesome details of the Nanking Massacre. Thousands of innocent civilians were buried alive, used as targets for bayonet practice, shot in large groups, and thrown into the Yangtze River. Rampant rapes (and gang rapes) of women ranging from age seven to over seventy were reported. The international community estimated that within the six weeks of the Massacre, 20,000 women were raped, many of them subsequently murdered or mutilated; and over 300,000 people were killed, often with the most inhumane brutality.

Dr. Robert Wilson, a surgeon who was born and raised in Nanking and educated at Princeton and Harvard Medical School, testified that beginning with December 13, “the hospital filled up and was kept full to overflowing” during the next six weeks. The patients usually bore bayonet or bullet wounds; many of the women patients had been sexually molested.

The international community had filed many protests against the Japanese Embassy. Bates, an American professor of history at the University of Nanking during the Japanese occupation, provided evidence that the protests were forwarded to Tokyo and were discussed in great detail between Japanese officials and the U.S. ambassador in Tokyo.

Brackman (reporter at the trial and author of the book “The Other Nuremberg”) commented: “The Rape of Nanking was not the kind of isolated incident common to all wars. It was deliberate. It was policy. It was known in Tokyo.” Yet it was allowed to continue for over six weeks.

The defendants were represented by over a hundred attorneys, three-quarters of them Japanese and one-quarter American, plus support staff. The defense opened its case on January 27, 1947, and finished its presentation 225 days later on September 9, 1947.

The defense argued that the trial could never be free from substantial doubt as to its “legality, fairness, and impartiality”.

The defense challenged the indictment, arguing that crimes against peace, and more specifically, the undefined concepts of conspiracy and aggressive war, had yet to be established as crimes in international law; in effect, the IMTFE was contradicting accepted legal procedure by trying the defendants retroactively for violating laws which had not existed when the alleged crimes had been committed. The defense insisted that there was no basis in international law for holding individuals responsible for acts of state, as the Tokyo Trial proposed to do. The defense attacked the notion of negative criminality, by which the defendants were to be tried for failing to prevent breaches of law and war crimes by others, as likewise having no basis in international law.

The defense argued that the Allied Powers’ violations of international law should be examined.

Former Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō maintained that Japan had had no choice but to enter the war for self-defense purposes. He asserted that because of the Hull Note, “we felt at the time that Japan was being driven either to war or suicide.}”

One defendant, Shūmei Ōkawa, was found mentally unfit for trial and the charges were dropped.

Two defendants, Matsuoka Yosuke and Nagano Osami died of natural causes during the trial.

Six defendants were sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace (Class A, Class B, and Class C):

General Kenji Doihara, chief of the intelligence services in Manchukuo

Kōki Hirota, prime minister (later foreign minister)

General Seishirō Itagaki, war minister

General Heitarō Kimura, commander of Burma Area Army

Lieutenant General Akira Mutō, chief of staff, 14th Area Army

General Hideki Tōjō, commander of Kwantung Army (later prime minister)

One defendant was sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes and crimes against humanity (Class B and Class C):

General Iwane Matsui, commander of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force, and Central China Area Army

They were executed at Sugamo Prison in Ikebukuro on December 23, 1948. MacArthur, afraid of embarrassing and antagonizing the Japanese people, defied the wishes of President Truman and barred photography of any kind, instead bringing in four members of the Allied Council to act as official witnesses.

Sixteen defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment. Three (Koiso, Shiratori, and Umezu) died in prison, while the other thirteen were paroled between 1954 and 1956:

General Sadao Araki, war minister

Colonel Kingorō Hashimoto, a major instigator of the second Sino-Japanese War

Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, war minister

Baron Kiichirō Hiranuma, prime minister

Naoki Hoshino, Chief Cabinet Secretary

Okinori Kaya, finance minister

Marquis Kōichi Kido, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

General Kuniaki Koiso, governor of Korea and later prime minister

General Jirō Minami, commander, Kwantung Army

Admiral Takazumi Oka, naval minister

Lieutenant General Hiroshi Ōshima, Ambassador to Germany

General Kenryō Satō, chief of the Military Affairs Bureau

Admiral Shigetarō Shimada, naval minister

Toshio Shiratori, Ambassador to Italy

Lieutenant General Teiichi Suzuki, president of the Cabinet Planning Board

General Yoshijirō Umezu, war minister

Foreign minister Shigenori Tōgō was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment and died in prison in 1949. Foreign minister Mamoru Shigemitsu was sentenced to 7 years.

The verdict and sentences of the tribunal were confirmed by MacArthur on November 24, 1948, two days after a perfunctory meeting with members of the Allied Control Commission for Japan, who acted as the local representatives of the nations of the Far Eastern Commission. Six of those representatives made no recommendations for clemency. Australia, Canada, India, and the Netherlands were willing to see the general make some reductions in sentences. He chose not to do so. The issue of clemency thereafter disturbed Japanese relations with the Allied powers until the late 1950s, when a majority of the Allied powers agreed to release the last of the convicted major war criminals from captivity.

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

Sources

Truman Library

Wikipedia

Law Virginia

Reblogged this on History of Sorts.

LikeLike