From 1987 to 1997, I worked for Philips. It was a global leader in electronics and is still a leader in healthcare technology. In 1991, it celebrated its 100th anniversary. We were promised a profit share, but due to cuts, that never happened. Instead, we received a book about the history—100 years of Philips.

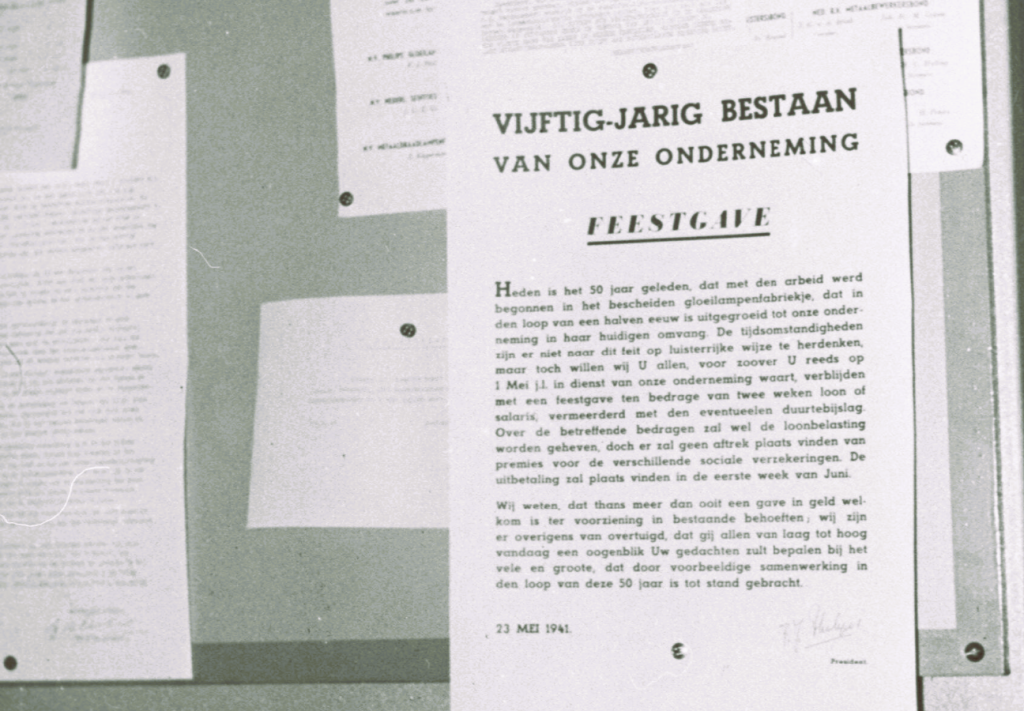

50 years earlier, the celebrations for the 50th anniversary were also not as they would have expected.

On May 23, 1941, Philips’ 50th anniversary was celebrated in Eindhoven. The staff spontaneously took advantage of the party to express their disgust with the occupation. The 17,000 employees took to the streets and chanted anti-German slogans. The shocked management rejected the action.

While Frits Philips addressed the attorneys and staff representatives in the Recreation Building in the morning, workers from the glass factories went to this building to thank him for the festive gift, namely two weeks of extra pay. On their way, thousands of employees joined us from all sides, passing in a long procession past the now-warned Frits Philips.

“… there came the thousand-strong Philips family in procession. Girls in their white assembly coats, men on carts, on electric factory carts, glassblowers with their iron rods, all decked out with orange or red-white-blue sashes, party hats on, bows in the hair…”

In the afternoon, thousands of exuberant employees gathered in the courtyard of the Philips factories on the Emmasingel, a fascinating spectacle according to company leaders, who asked Frits to also come to the Emmasingel. Congratulations followed, and hands were shaken. Everyone wanted to see and talk to him.

After the employees were given the time off, the party really started, according to Frits Philips. Everyone entered the city singing and dancing. In a large parade, they marched past De Laak, the home of Anton Philips on Parklaan. When surprised or dismayed German soldiers ended up in the procession, teasing and demonstrations of patriotism ensued. Reportedly, even the car of the German Commander-in-Chief was decorated with a red, white, and blue flag. NSB members were loudly asked questions of conscience; one of them, a police commissioner, Dijs, was wounded in the arm by two stab wounds after he had given a girl a serious head wound with his sword.

The Philips Harmonie turned out to pay a musical tribute at “de Laak,” the home of Frits Philips. Thousands and thousands followed the men of conductor Kees van der Weijden. He was allowed to let them play whatever he wanted, and over everything, the “Orange above, Orange above, long live you-know-who!” resounded again and again—and that in the middle of the occupation, in a city full of German soldiers.

The German soldiers at the Philips exits did not understand it at first.

During the war, Germany used Philips factories. Radios and transformers: they are important for warfare. This also means that the factories are an important target for bombing.

Philips, Frederik J. Frederik (Frits), the president of the huge Philips Company employing thousands of people, was the only member of the company’s directorate who did not flee to America when the German army invaded the Netherlands. He felt that he was responsible for both the continued operation of his enterprise and the welfare of those among his employees who were threatened by the Nazis’ racist laws, the Jews. Frits was harnessed to two aims. First, he had to comply with German demands for the increased output of products deemed essential for the war effort and a decrease in the production of consumer goods for domestic use. On the other hand, he was determined to protect his Jewish employees and their families from deportation. In German circles, Frits was known to have “Jewish sympathies,” which he did not try to hide. Simultaneously, though, he was forced to collaborate with the Nazi government-appointed director of Philips in order to avoid losing his influence completely. After some time, the conflict could no longer be harmonized, and his desire to save Jews and sabotage the German war effort became dominant. In December 1941, Frits created two special divisions of Jewish employees, one in Eindhoven, where the large plant was located, and the other in Hilversum, which housed another smaller branch, the NSF. These branches were known as SOBU, the Special Orders Bureau. Frits had initially rejected the idea of having Jewish units for obvious reasons. Still, as the deportation of Jews seemed imminent, he became convinced that racial segregation in his company might actually work to his employees’ benefit. By January 1942, the SOBU group in Eindhoven consisted of 83 people (and soon grew to 94), and the one in Hilversum numbered 20. The groups, physically separated from the rest of the company’s employees, were given simple technical tasks which, in many cases, were neither suited to the individuals’ expertise nor their level of training.

Nevertheless, the Jewish employees accepted the segregation. The company accepted the lowering of standards, and these workers were spared deportation for the time being because they were ostensibly contributing to the German war effort. In another life-saving effort by Frits, he managed to institute free supplementary food rations from the city authorities to his employees with the approval of the German authorities. Soup, mashed potato, and carrots mixed with meat (a popular Dutch dish), was thus supplied to the workers at no cost. The dish was affectionately called Philipprak, “Philip mash.” At the end of 1941, 20,000 portions of it were dispensed from the kitchens, especially set up to prepare it in the city of Eindhoven. From January 1943, the Philips plant itself took over the task of making and distributing these meals. In early 1942, the Germans began to implement their plan to concentrate the majority of Dutch Jewry in Amsterdam. The first Jews ordered to move there were those living nearest to the city. When, in May 1942, the Hilversum SOBU was ordered to move to Amsterdam with their families, a decision was made and approved by the German authorities to move the entire group to Eindhoven instead. In effect, there was only one SOBU group from this time on. Over the course of 1942, Frits tried to arrange for members of the group and their families to leave the country by obtaining exit visas for them. To this end, he demanded a sum of $2,000,000 from the Philips Company in New York.

The request was made in a letter sent through illegal channels in which it was stated that the funds could be transferred to the German authorities in the Netherlands in return for 400 exit visas for Jewish personnel. In drawing up this plan of action, Frits cited an instance in which the Germans had agreed to the emigration of six groups of Dutch Jews to South America in return for money and the planting of spies. In the response from New York, the Philips Company stated that it had no objection to paying this sum but that the American government could be expected to veto the plan. While the SOBU members were waiting for the arrival of their visas, they were protected by the “120,000” “sperre” stamp obtained by Frits. In the end, the plan never materialized. On June 30, 1943, the German authorities officially rejected Frits’s emigration request. During this time, developments in the war complicated the situation for Frits and his workers. Great destruction was caused when the RAF bombed the Philips factory on December 6, 1942. In February 1943, the management of the Philips Company went along with a German proposal to establish a work site in the Vught concentration camp for the inmates there. Frits agreed to relocate the production line in Vught but with a number of provisos. Among his stipulations was the demand that Philips would be permitted to provide supplementary hot meals, the “Philipsrak,” to all its employees in Vught. Philips continued to pay monthly salaries to Jewish employees who went into hiding if their addresses were known. After the war, surviving Philips employees were given full salaries for the years they worked unpaid during the war. Initially, the leaders of the Philips work team in Vught were convinced that Vught was not a way station to the east. However, after the deportation of Jewish women and children from Vught, though not from the Philips plant, on June 7, 1943, they had no more illusions. From that day on, the Philips management drafted as many Jews as possible into the Philips-Kommando, as the work battalion at Vught was called. They hoped that they would be able to save Jews from deportation if the Philips concern protected them. And it did until June 1944, eight full months after the last roundup of Jews in Amsterdam. In April 1943, when a general strike broke out across the Netherlands in protest against the mass deportation of ex-Dutch soldiers to Germany as POWs, the Philips plant was completely paralyzed. Frits, still very influential although long ago replaced as the acting president of the company, tried to work out a compromise. However, the SS acted more quickly than he could to quell the strike, imprisoning almost the entire board of directors, including Frits. He remained incarcerated until September 20, 1943. When Frits finally returned to the plant in October 1943, he found himself stripped of his former powers and unable to exert any influence. Meanwhile, in Vught, Jews, even those in the Philips-Kommando, were being deported. On September 23, 1943, the German management declared that of the 1,800 Jews still in the camp, only 400 could stay. The rest had to be deported over the following few months. An intense effort was made to save whoever could be saved based on the presumption that the only criterion that the authorities would accept to exempt someone from deportation would be the person’s contribution to the war effort. However, on June 2, four days before the Allied forces landed in Normandy, all the Jews still in Vught, including the original members of SOBU and a group of men, women, and children under the age of 14, inmates who worked for Philips, were deported directly to Auschwitz. Altogether, the Philips-Kommando group that arrived in Auschwitz on June 7, 1944, numbered 496 people—391 women, 90 men, and 15 children under the age of fourteen. Of these, 325 women arrived in Sweden on May 4, 1945; 11 women and 10 children arrived in Hamburg in May 1945; and 40 men returned to the Netherlands—a survival rate of 77.8%. Among the survivors were 48 SOBU members out of a group of 87 SOBU deportees to Auschwitz—a survival rate of 55.1%.

On July 20, 1944, Frits went underground. After being warned that a number of SD members were on their way to arrest him, he left his office through the window and fled to an unknown address. For several weeks, his wife, Sylvia Philips-van Lennep, managed to lead the Germans astray by subterfuge. However, when Frits did not return from his “vacation,” she was arrested and taken to Vught. There is no doubt that Frits Philips and his co-workers were instrumental in saving many Jews, driven solely by concern for the welfare of their Jewish employees. After the war, Frits traveled to Götebörg, Sweden, to meet the women of the Philips group there. It was a very emotional meeting. On July 18, 1995, Yad Vashem recognized Frederik J. Philips as Righteous Among the Nations.

Sources